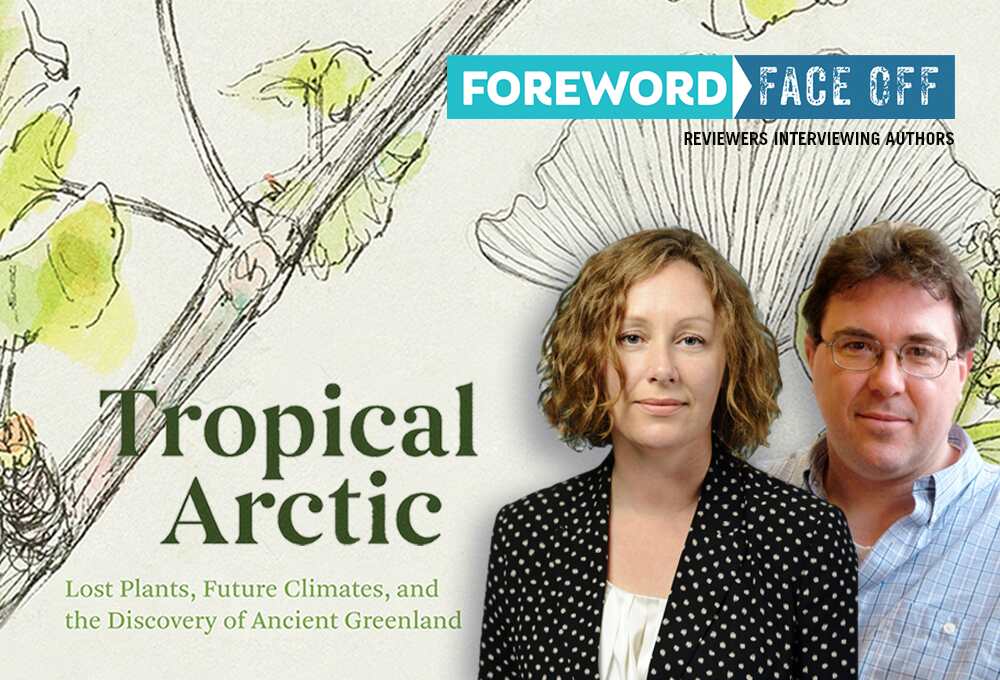

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Jennifer McElwain, Ian Glasspool, and Marlene Hill Donnelly, Authors and Illustrator of Tropical Arctic: Lost Plants, Future Climates, and the Discovery of Ancient Greenland

Earth, you old frigate, sailing the galactic winds for billions of years, taking fire from pesky meteorites, nurturing ever-evolving flora and fauna, shedding same in frantic spates of extinction, all while staying true to your polar axis (mostly). As your most curious inhabitants, we humans are gradually learning your vexing secrets—even as we cause you irreversible harm.

We were fascinated to learn from this week’s interview guests—scientists Jennifer McElwain and Ian Glasspool, along with illustrator Marlene Hill Donnelly—that some of your coldest present day

regions were once some of your warmest. In their new book, Tropical Arctic, they detail the peculiar case of now icy Greenland, as well as myriad examples of how you came to master life after three billion years or so. In a starred review in Foreword Reviews, the top review journal for independently published books in North America, Rachel Jagareski writes that the book is “engrossing as it relays the dangers of exceeding the limits of plant and animal resilience and overheating an already too hot Earth.”

So, home of ours, majestic cathedral that you are, know that many of us are very concerned and will continue doing what we can for your wellbeing.

Enjoy the interview.

The sites you discuss in your book, dating from the boundary of the Triassic-Jurassic great extinction event and overheating of the planet, are part of deep time, yet have relevance to current global warming. Jennifer and Ian, when you first decided to study paleobotany, did you have any inkling about how relevant your research would be in understanding implications for the ongoing climate and biodiversity crises?

Jennifer McElwain: I became interested in palaeobotany as a first year undergraduate student at Trinity College in Dublin. It was the first time that I was exposed to the concept of deep geological time and the idea that every living species has a history and that landscapes in the past were very different from those of today. Towards the end of my degree, I started to use Willow leaf sub-fossils (only 9,000 years old) to test if we could use them to reconstruct atmospheric composition in the past. This early undergraduate research experience demonstrated to me the great potential of using fossil plants and their innate plasticity and responsiveness to their environment as a means of reconstructing the past. Of course, at that stage I had no inkling just how important palaeobotany could be, all I knew was that I was hooked.

Ian Glasspool: I first got hooked on paleobotany thanks to a can of baked beans! This can of beans was offered as a much desired prize in class to the student who could best taxonomically differentiate its contents from those of acritarchs, a “dustbin group” used to encompass enigmatic organic microfossils. This may not say much about my tastes (or state of finances) at the time, but back then it was indeed a strong motivator for me to hone my taxonomy skills. I guess this is a long-winded way of saying that the climate and biodiversity crises and my role in understanding their implications weren’t so much on my mind then, as was the relief of hunger in the impoverished.

The Greenland field conditions seem so daunting. Aside from being alert against polar bears who might want “a light snack of unwary scientists,” you describe hazardous and strenuous hikes to fossil sites, and the staggering costs and logistics of helicopter transport of people, supplies, and tons and tons of fossil specimens. Then there were the stiff winds that blew away delicate plant structures just when you released them from millions-of-years-old rocks! What was the most difficult aspect of the expedition as you look back?

Jennifer: The logistics of planning food and supplies for five people for a month in an Arctic environment was the most challenging aspect for me. I had no idea how much we would all eat and kept making endless lists of all possible pieces of kit that we might need. Once you are in the field in Greenland there are no opportunities to pop to the local shop as there is none.

We were also restricted in terms of the food we could pack—no tins was a challenge! We sent out two twenty-pound wheels of Parmesan cheese and cured sausage for protein but it arrived two months in advance of the expedition. It was fine once you scraped the outer layer of mould off.

The mosquitos were also challenging but once there was nowhere left really to bite on exposed parts they seemed to lose interest. We also had head nets and could eat inside the tent when the mosquitos were really bothersome.

Ian: I’m extremely vertiginous, so for me, the heights and narrow ledges of the Neill Klinter won hands down as being the most difficult aspect of the trip. With that exception, it’s a toss-up between the bathing and the realization that we had forgotten to pack any tea. I survived the latter, but it was traumatic. As for the bathing: when we visited the southern Cap Stewart Peninsula, other than the Hurry Inlet itself with its mini and not-so-mini icebergs washing onto the beach, there was only one good bathing option, a small stream flowing down Rævekløft. Each morning I would sit on a little sandy meander bank where, for some unbeknownst reason, there was a driftwood tree trunk. It’s only writing this now that I realize how strange that was. Living in Maine, dead trees on the beaches or in our streams are not uncommon, but this was treeless Greenland.

Anyway, I’d sit on the trunk wrapped in umpteen layers and look at the water, and in particular one deep pool. After the first time I knew how head-spinningly cold this melt-water stream was. The first hurdle was to undress rapidly to give the mosquitoes as little chance as possible, then throw my shampoo bottle into the deepest part of the pool, so that I would have to go and get it. Once in, the experience did not get better; it was a case of clean up as quickly as my numb fingers would let me, stumble on numbed legs out of the water and towel off and dress as fast as possible to avoid my bloodsucking friends. That being said, there was then a blissful moment where any morning sun would feel like one of those heat-lamps on a Chicago L station during January—an absolute heavenly experience.

Marlene, your resplendent depictions of the ancient landscapes can be equally appreciated for their beauty and the richness of their science-based detail. I particularly enjoyed reading about your field trips and studio experiments with modeling plants to better understand the form, function, and color palette of your envisioned landscapes. Was this project your first time analyzing and visually recreating an ecosystem without illustration precedents?

Marlene Hill Donnelly: Tropical Arctic has indeed been a uniquely wonderful project. Field sketching and travel have always been two loves of my life, so illustrating this book was pure joy. When I needed to learn how a flood plain differs from a lake or pond, several days of sitting in the midst of recently flooded forest, sketching, listening and writing, opened a whole previously invisible new world. I was literally immersed and so a bit uncomfortable, but it was worth it.

Embedded in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park every year over many years of eruptions brought me not only accurate visual observations but also the visceral impact of thundering explosions, the breathtaking heat of lava inches away, and seeing how fast I can run.

Wading and sitting to draw in the incredibly hot water of a Washington state bog brought a new realization of the incredible toughness and adaptability of certain plants. Ferns in a hot tub! This strongly influenced the illustration of the Disaster Bed and explained to me, on a gut level, the demise of the unfortunate majority of less adaptable plants.

Sketching the Okefenokee Swamp from a kayak brought insight about a wonderful, ancient environment of sudden rolling storms, frequent fires, and hidden, hungry reptiles. Devoted mother alligators were ever-vigilant in protecting their young from dangerous invading artists, resulting in several more exciting races.

Since I wasn’t comfortable relying on previous illustrations for the way fossil plants held themselves in life (I don’t like making assumptions or making things up), the only option seemed to be serious engineering experiments to see how upright (or not) leaves of a certain size and thickness could possibly be. Experiments based on expert advice from mechanical engineers yielded some real surprises! And I only set my studio on fire once using the necessary blowtorches.

Your book points out that eighty-five percent of the plant species at the Astartekloft fossil site became extinct after the “wholesale ecological reordering” of the Triassic-Jurassic warming of Earth’s temperature. You also soberly note that we are enduring accelerated rates of warming than occurred then. Which plants and animals do you think are most resilient and most likely to survive the Anthropocene era?

Jennifer: This is the BIG question that we are all still trying to answer and it is so complex. The Greenland work demonstrates that species which are perhaps overlooked because they are not very abundant may be the ones to take prime ecological place under a warmed world. In a way this is counterintuitive because we often consider rare species—that is, those that are only found in very few places on earth or in very low numbers in a forest, are most threatened by climate change. This is most likely the case. However, one of those incredibly important rare species will be pre-adapted to new climate and warmer conditions. For me this highlights why we must protect and conserve all species and value all our biodiversity.

Ian: I would put in a vote for Blattodea (cockroaches, etc). They’ve been hanging in there for at least 300 million years and we seem to be giving them just what they need to thrive. As for plants, again I’d look to the fossil record, and in terms of longevity and morphological stability, the horsetails seem to be as tough as old boots.

The now multi-year COVID pandemic has diverted public attention away from the important climate change fight. Are you generally heartened or discouraged about government and corporate efforts to dramatically reduce greenhouse gases and make other changes in policy and personal consumption?

Jennifer: To be honest, I flip between both. Today, for example, I have just read about new research at my university on safe storage of hydrogen gas—this makes me feel very hopeful that more and more new green technologies that do not emit greenhouse gasses are being developed. We have the technology, we know the consequences of inaction. There is no excuse and there are no other options but to meet the Paris Climate agreement and keep fossil fuels in the ground.

Ian: While COVID-19 has grabbed the headlines, I think it’s also focused many people’s minds on 1) just how susceptible to global scale events the human race can be, and 2) how rapidly and catastrophically those events can unfold. However, do I feel optimistic? Not just yet!

How do you balance your careers with being advocates for climate change? Are passion and actions calling for changes in public policy and behavior becoming more acceptable in the scientific community?

Jennifer: This is a great question. In a way all academics try to make a difference by educating the next generation and undertaking research on the difficult questions. I personally do not feel well equipped to drive policy change and behavioral change because I do not have the expertise or skill set to do so. However, I think we can all tell stories and try to communicate clearly and simply, and perhaps quietly, from our own expertise. When people repeatedly hear these stories told in different ways and through different mediums, perhaps something will resonate and more and more governments will start putting in place targets and policies that set us on a more sustainable future.

Rachel Jagareski