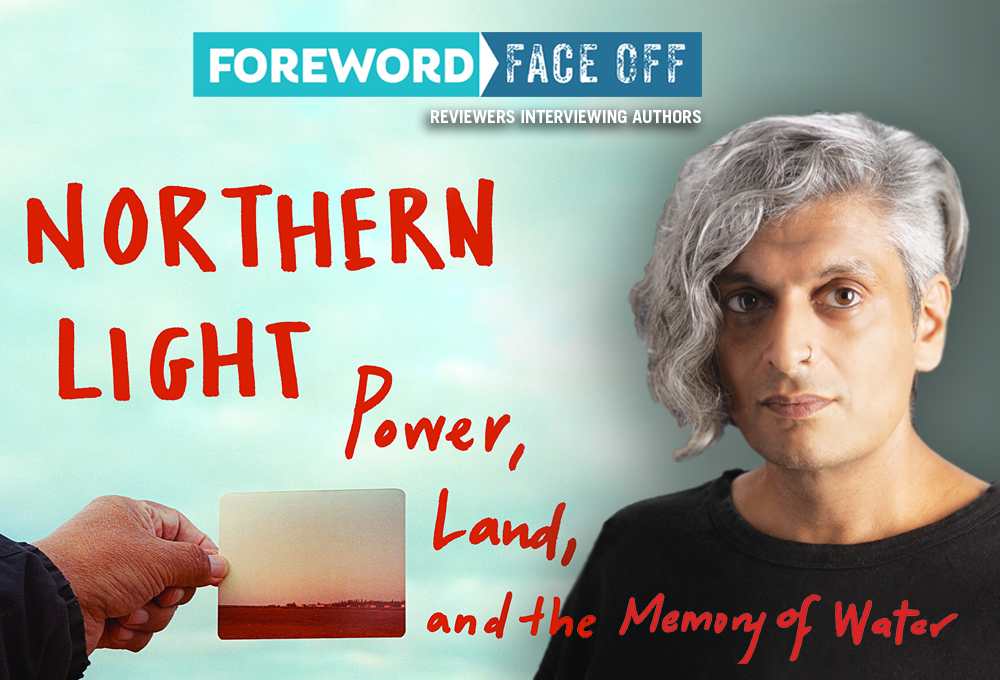

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Kazim Ali, Author of Northern Light

It doesn’t happen but a few times a year but when a book like Kazim Ali’s Northern Light comes along our excitement is palpable—but the happy discovery also bears with it the duty and responsibility we have to alert our readers and partners. We’re watchdogs for the book industry, and this lyrical tale of reconnection and self discovery deserves all the attention it can get.

Managing Editor Michelle Schingler entrusted the Foreword review to Rachel Jagareski, one of our surest pens. In her starred review for the Jan/Feb issue, Rachel writes that what began as Kazim’s nostalgic inquiry into his childhood home of Jenpeg, Manitoba, and the Indigenous community nearby, soon “grew into an exploration of human connections to land and water, personal and cultural identities, and the meaning of home.” In “sensitive, crystalline prose,” Kazim shows how the Pimicikamak residents on provincial and reservation lands “are working to reinvent their town and rebuild their traditional beliefs, language, and relationships with the natural world.”

In the interview below, Rachel asks Kazim to talk about how his South Asian Muslim heritage influenced his relationships with the Indigenous residents of his northern home, and his answers are both enlightening and deeply moving.

Rachel, please take it from here.

“Who’s going to read what a poet has to say?” Your early comment to fellow poet Layli Long Soldier was an arresting bit of dialogue. As I read further about your return to your childhood hometown of Jenpeg and nearby Cross Lake, however, I saw how powerfully you use language to uncover the complexities of cultural and personal identity and our relationships with the natural world. Do you think that your poet’s skill in distilling complex ideas and feelings into words was essential in telling the story of this region, its culture, and why there is such a horrifying suicide epidemic among its young people?

I suppose I felt that the situation was so far beyond me—forty years of environmental damage, many more years of colonial violence and degradation before that—that anything I might write about would be useless, pointless for anyone other than myself. I should say that when I went, I didn’t really know what I would find, nor the scope of what I would write. I thought it would perhaps be a more personal meditation on the concept of “home,” and touch on the colonial relationship between the immigrant and the Indigenous, but as you can see, almost immediately upon arrival the “poet” realizes the story isn’t about him, nor is the role of the “poet” going to be the one role that will serve in this situation.

As far as the suicide epidemic goes, you’ll see that I never really try to address the question “why”—or rather, my entire journey and account of the journey centers on that question but does not try to reduce it. There is no “why,” or rather everything is “why.” I also—besides my conversations with Anna McKay, the principal of the Mikisew School, and Chief Cathy Merrick—do not really talk about the suicide epidemic with the people I met. I thought briefly about asking to meet more students, but it felt—I don’t know how to say this—intrusive in some way. There is an amazing CBC documentary (that I mention in the book) called Cross Lake: This is Where I Live, in which the Canadian broadcast journalist Gillian Findlay goes to Cross Lake and talks to some of the students directly affected, either because they knew people who died or who had attempted suicide. I think it was possible for her precisely because she was a journalist and that only. My position in the community felt more complex.

The contrast of your “wanderer” background growing up in a big peripatetic South Asian Muslim family, and the more rooted Pimicikamak residents you meet, is a striking recurrent theme. At times you seem wistful and nostalgic about your “real hometown” of Jenpeg and yet your career as a writer and teacher would not be possible if you still lived in a small, isolated area. What pull does Jenpeg have on you now that you’ve experienced it as an adult?

The Pimicikamak—all First Nations people in Canada—were uprooted: culturally, geographically when they were sent to the residential schools or had to leave the reserve for work, linguistically, and so on. Any sense of “rootedness” there is against these hundreds of years of attempts by European and Canadian authorities to erase them or at very least diminish them. It continues to this day.

“Jenpeg” couldn’t be my hometown, shouldn’t be, and yet those feelings of nostalgia and loss are ever-present. I have called myself, in my life, American, Canadian, Indian. I have not called myself English, British, or Pakistani, though those are equally part of my ancestry, birth, and cultural heritage. So we are “from” the places that resonate within us. I never even knew the name Pimicikamak before I went back. Now I know the name and I know what it means: “where the river crosses the lake.” Pimicikamak is literally a land defined by its water.

The provincial and federal governments should have known the value of what the community was giving when they agreed to allow the damming of the river. They should have respected that gift.

The Pimicikimak communities in Cross Lake seem divided in so many ways: some live on provincial land, some live on lands never ceded to Canadian authority; some maintain traditional beliefs while others are Christian; some support settling treaty claims while others push for more litigation. How do you see these conflicts resolving in the next few years? Do you think the different Cross Lake constituencies will come together to tackle shared problems like youth suicide, shore erosion, degradation of fishing and hunting lands, lack of health care, housing shortage, etc?

It’s a very dynamic community with a high level of civic participation and an educated populace. I describe their governance structure—which is a direct democracy—in the book, but witnessing it first hand was something else. I attended a community meeting about a particular piece of Canadian legislation on children’s healthcare (Jordan’s Principle) and the thirty or so people who were there knew this legislation backwards and forwards. They were studied up on its impacts and implications—it was stunning, I’ve never seen anything like it. Certainly not in the US where people routinely believe completely fabricated conspiracy theories as reasoned fact.

The discussion around remedies for the challenges facing the community are robust and very invested in creative solutions, but they require buy-in in the form of material resources from the provincial and federal governments. The amount of revenue generated from the dam over the last forty-plus years is unspeakable. Pimicikamak should be compensated fairly and past what the treaty allows because the base-line environmental preservation provisions were not met. Some solutions—K-12 education using Cree as the primary language of instruction—is already happening, but much more is planned and it requires provincial and federal investment. This dam—built by Canada to provide cheap power to Canadian cities—is not located in Canada: it is built on land that has not been ceded.

From the very beginning Pimicikamak distinguished itself among First Nations. While other communities were welcoming Christian missionaries and allowing them to build churches, Cross Lake refused. Even when the referendum was held on whether to ratify the treaty and allow construction of the dam (irony of ironies: Manitoba Hydro broke ground on the dam in 1975 while the treaty was being negotiated; it wasn’t presented for ratification until 1977), the vote in Cross Lake passed by only a few percentage points as opposed to the significantly wider margins in the other four First Nations impacted by the dam and covered in the treaty.

You note that Prime Minister Trudeau’s actions supporting oil pipelines, more hydroelectric dams, and other projects benefiting the fossil fuel/mining industries belie his verbal support of First Nations rights. However, there are hopeful signs on the horizon with the end of the Trump administration, cancellation of the Keystone Pipeline, public and investor support for green energy initiatives and even some restoration of previously dammed rivers in the Pacific Northwest. Do these actions make you feel more positive about Cross Lake’s environmental future?

I am going to say that I am cautiously optimistic. The US and Canada are substantially different situations. A long time ago the US already did what Canada has not yet done, which is outright seize resourced areas, i.e., those with gold or oil or either kinds of resources the settler government wanted for itself. As of this moment, Canada still (in name anyhow) respects the treaty lands that were unceded. The building of the Jenpeg Generating Station did require a treaty (though as I mentioned, it seemed in name only since ground broke on construction before any treaty was developed or signed). So things in Canada could get a lot worse (seizure of Pimicikamak land outright) or they could, as you suggest, get better.

The work of Ingrid Waldron (she focuses on Nova Scotia) points out how environmental crises disproportionately affect Black and Indigenous peoples in Canada. It remains to be seen whether the larger body politic realizes the long-term benefits of environmental sustainability and remediation to the society as a whole.

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended peoples’ health and lives all over the world, but Indigenous communities have been particularly brutalized. You discuss Chief Cathy Merrick’s work in trying to get a hospital built in Cross Lake, but this was still in the negotiation phase as of your book’s epilogue. How is health care in Cross Lake holding up during this time?

The first big earmark for the hospital, to the tune of $40M, happened in 2016 and at that time, the hospital was expected to be complete within five years. I first went in May of 2017 and it had not yet broken ground. At the completion of the book in the fall of 2020, the hospital had not yet been built. People leave the community for Thompson (a mining city a little further north) or else go south to the provincial capital, Winnipeg, for more serious medical needs.

Cross Lake was one of the earliest communities in Canada to lockdown back in March 2020 and has kept careful attention to quarantining. Nonetheless, as of November 2020, there were twenty-three cases of COVID-19, fifteen people who live in the town and eight people who live out of town. Four people had recovered. It’s difficult to isolate there because so many people live in communal living arrangements. For a population of 8,600, there are about 1,200 houses.

The good news is that a batch of Moderna vaccines has arrived, enough for two doses for everyone over the age of 70. Hopefully they will get enough vaccine for everyone soon.

What other literary projects are you working on presently? Do think that you will revisit Jenpeg in person and on paper?

I have gone back to Jenpeg and Cross Lake since the original writing and was planning another trip this past year that had to be canceled because of the public health situation. Once things are cleared, I am hoping to go back. I have stayed in touch with many of the people I write about in the book, and saw many of them on my subsequent trip. It’s a community that I still feel a part of. I want to work with community members to tell their own stories, and am hoping to provide support of youth cultural and recreational programs.

Writing about Cross Lake and Jenpeg has inspired me to try to write about my experiences teaching yoga in Palestine. Beginning in 2011, when I went to visit a former student who was working as an English teacher in Ramallah, I have been teaching yoga classes at a yoga studio in Ramallah. On my first trip I taught open classes and on subsequent trips I began training yoga teachers. I wrote a long account about teaching in Palestine, the principles of yoga, and about training teachers. It’s been sitting on my desk for years because I was unsure what to do with it. I now understand that it is a book, and a vital story that must be told. So that’s what’s next for me.

Rachel Jagareski