Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Rebecca May Johnson, Author of Small Fires

Eureka! moments happen in the shower, on the pilgrims’ trail, while headscratching, and, in Rebecca May Johnson’s case, while making tomato sauce for the umpteenth thousand time. Suddenly, the way she went about preparing the recipe became “wild, paradigm-shifting, ecstatic,” and changed how she approached the rest of her life.

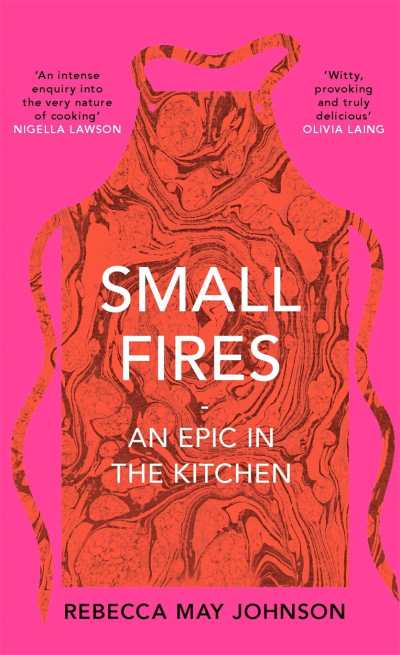

Rebecca’s experiences are captured in Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen, which earned a starred review from Rachel Jagareski in Foreword Reviews. Rachel calls the book an “intense, revelatory reconsideration of cooking, treating it as important work that can be liberating, intimate, imaginative, erotic, and heroic.”

Cooking can be all of those things, BUT for many, it is stressful, maddening, and one of the many ways our capitalistic system has disadvantaged women.

Heady stuff. Rebecca and Rachel don’t shy away in the interview below.

Your aim of learning to think and cook critically as a way of resisting the patriarchal history of knowledge really comes through in this book. You consider this all through the lens of your “hot red epic,” the tomato sauce recipe developed over ten years, ten kitchens, and thousands of iterations. What drew you to this recipe as your focus?

Every time I tried to think about what I knew about cooking and to identify the moment when I developed a meaningful understanding of it, I came back to this recipe. Occasionally in life, I gain a transformative insight that changes how I see the world and how I live—often this has been through study or reading, and from talking to people. This recipe brought about such a transformative moment, too: the first time cooking the recipe was a wild, paradigm-shifting experience—revelatory and ecstatic!

I suddenly perceived ingredients and the processes of cooking as never before. The recipe gave me principles for understanding so much beyond that one dish and became a kind of grammar that enabled me to speak through cooking—to express myself, and to communicate. As I began to document all the times I had cooked the sauce, I realised how much of my life was contained in the recipe, how many relationships of all kinds had come into being while making it.

As you note, so many chefs and contestants in the ubiquitous crop of food television shows cite inspiration from a beloved grandmother who “cooked with love”; what they don’t also acknowledge is the physical labor, creativity, and chore of putting food on the table everyday. Can you elaborate on why this is?

In Wages Against Housework, the feminist theorist Silvia Federici writes that in the capitalist system, housework including cooking, has been denied a wage and become transformed into an act of love as a strategy to deny its status as work. Federici writes that capitalism “had to convince us that it [housework] is a natural, unavoidable and even fulfilling activity to make us accept our unwaged work.” Unpaid housework financially benefits business owners whose workers are fed and cared for gratis—imagine how high wages would have to be if every worker had to pay the person caring and cooking for them out of their wage.

The legacy of this is that in the private family home, the work of cooking is often regarded as solely a gesture of love and is experienced as such by people growing up in those homes. Of course, cooking can be an expression of love and care and many of us cook out of love sometimes—I would never deny that!—but that is far from the extent of it. The characterisation of cooking as a “natural” expression of “feminine” love also acts to conceal the difficult work that cooking is, and the extent of the work it involves, and the fact that those expected to do it sometimes (and sometimes often) do not want to cook, or actively dislike cooking, and do not cook with love. And also, the pervasive image of the loving cook represses the fact that women such as these idealised grandmothers are often living with an expanse of complex emotions beyond a simple expression of love.

Small Fires explores the differences between cooking for one’s self and cooking for others. I was intrigued to consider how you view cooking as a performance and how it can be a transformational, intimate act between the individual and others. What kinds of guests do you most enjoy feeding?

I enjoy the challenge of cooking for most people, I think. It’s fascinating to get to know people through cooking, finding out about what people like to eat and cooking for them is a little like composing a portrait. At a bigger meal with more people, where it’s broader brushstrokes, it’s nice to cook for people who recognise that you’re doing your best and are up for participating in the spirit of the occasion. But I also know that many people find food stressful, so honestly whatever goes. I just want people to be happy!

How did COVID-19 affect your research and writing of this book?

Because I wrote my book during the pandemic, where for much of the time it was not really possible to leave the house—I couldn’t go to the library—however, this meant that I did not have the opportunity to kid myself that some tangential research was going to be the solution. I had to sit with the information I had, which was over a decade of cooking and living with different people and studying. Accepting that as “good enough” material was essential to writing the book, though, of course, via the internet and books at home, I could do some further reading.

It also gave me the impetus to treat the kitchen as a significant space for research, which turned out to be fundamental to the book (especially, the Winnicott X sausages chapter!). When I am anxious about a project, I have a tendency to think the solution is out there, somewhere else than where I am, and as a result, I fail to see what is right in front of me. The pandemic meant I had to stay where I was and work with what I had; I grew to appreciate the richness of what I had.

I was unfamiliar with the academic field of reception studies and how it examines classical texts and how they are translated and interpreted by different voices. Your treatment of the red sauce as an epic text worthy of scholarly examination digs into so many themes about gender and power. Have you received any feedback about this kind of rigorous analysis of a recipe?

I have received some generous words of appreciation from students and scholars, as well as from general readers who cook and who found the translation metaphor a useful way for understanding their own processes. There have also been readers who felt that the analysis of the word “lovely” reflected their own experiences of being patronised through working with food at home and professionally. One woman at an event said “it’s like you can see into my head!”

As for an academic reading of the book: not yet! Though I have heard it’s been put on some university courses, so perhaps it’s to come.

Your creative use of language and different genres throughout this essay collection was delightful. What other writing projects are you developing now?

That’s really wonderful to hear. Thank you! Although writing Small Fires was challenging, I had fun with it too, and remembering how to play was an essential part of the process.

I’ve just finished some essays that will come out in the next few months, and I am developing a second book that extends the approach taken in Small Fires to different spaces. I am both excited and nervous: a new writing project is an adventure of thought and feeling!

Rachel Jagareski