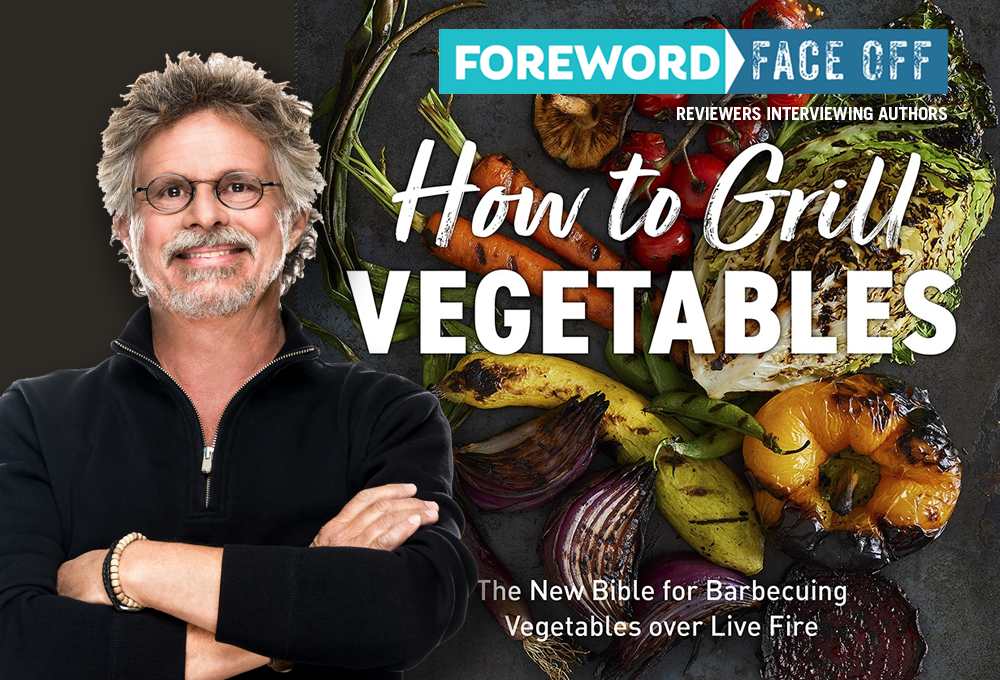

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Steven Raichlen, Author of How to Grill Vegetables: The New Bible for Barbecuing Vegetables over Live Fire

If you have a grill in your backyard and keep a few cookbooks at hand, you likely know the name Steven Raichlen, author of more than thirty books, grillmeister on several international cooking shows, and a shoo-in into the Barbecue Hall of Fame in 2015. Let’s also recognize the fact that he has a degree in French literature from Reed College and earned a Fulbright scholarship. The man writes as well as he bastes.

Rachel Jagareski honored his latest, How to Grill Vegetables, with a coveted starred review in the May/June issue of Foreword—which inspired this tong-’n-cheeky conversation.

Kudos for writing such a fun and creative book about grilling vegetables. The barbecue world typically has a laser focus on meat, but your new book excitingly shows off so many inviting ways to grill vegetables of every shape, size, and color. What was your main reason for wanting to move vegetables “from the periphery to center of the plate” with this grilling bible? Health? Environmental sustainability? Culinary variety?

Thank you. All of the reasons above. (And especially aesthetic: there’s no better way to cook a vegetable than on the grill. The high dry heat of the fire caramelizes the natural plant sugars, adding a smoky dimension you just can’t achieve in the kitchen). But actually, what got me started down this path was my family. My daughter and cousin became vegetarians. My wife has strong vegetarian leanings. So you could say I wrote this book in self defense!

When you are not traveling, how often would you say you typically fire up the grill each week? Do you have any tips for those of us who live in snowier areas to inspire us to shovel off the grill and keep barbecuing through the winter?

We fire up the grill virtually every time we cook at home (four to five nights a week). That includes breakfast, by the way. I love to cook breakfast on the grill. (See the Grilled Portobellos with Wood Fire Eggs on page 242.) And of course lunch: (see the Raichlen lunch quesadillas on page 117).

It is so helpful that you have variations in your recipes to accommodate cooks that own the different kinds of grills, smokers, and accessories. I notice, though, that you don’t include information about using electric grills. My go-to barbecue expert is a friendly butcher at the local supermarket meat/fish counter who rhapsodizes about his electric grill. Why the omission in your book?

I operate in the realm of live fire. That can be generated by wood, charcoal, gas, pellets, smokers, even handheld smokers, like the Smoking Gun. I don’t put electric grills down but most of the recipes in this book can be adapted to an electric grill. It’s just not what I do.

When you started out as a writer, did you ever imagine you would become such a well-known and well-traveled barbecue authority? What inspired you to focus on this type of cooking?

Definitely not. I have a degree in French literature. When I graduated, I thought I’d become a professor of comparative literature, writing novels on the side. (I actually did publish a novel in 2019—The Hermit of Chappaquiddick—check it out on Amazon.com.) After college, I went to France to study medieval cooking in Europe on a Thomas J. Watson Foundation Fellowship. During that year, I decided to become a food writer. I started as restaurant critic for Boston Magazine, then wine and spirits columnist for GQ. Somewhere along the way, my mentor, Anne Willan of the La Varenne Cooking School in Paris, told me: “Steven, you’ll never make a living writing cookbooks.” So I built my career trying to prove her wrong.

The barbecue thing started in 1994 with a very simple but profound realization (the Japanese would call it a satori). Grilling is the world’s most universal cooking method, but every country and culture does it differently. So I decided to travel around the world documenting how people grill in different cultures. The result was The Barbecue Bible (my first million-plus copy bestseller). And that’s how I got into barbecue.

Whenever we host a barbecue or are invited to someone else’s party, it always seems that the barbecue chef is chained to the grill and doesn’t have as much chance to socialize. Do you have any advice on how to get more people involved in the cooking or prep or other tips for having more fun and less work?

Very much so. Cook a communal dish in real time with everyone gathered around the fire, for example, the vegetable paella on page 206.

Or cook a sharable dish you can do ahead of time, like the smoked acorn squash with parmesan flan on page 195.

But the best way to spur socialization is to give everyone tongs and have them gather around the fire to help with the grilling.

Your long list of books has seemingly covered every aspect of barbecue cooking and has explored other ingredients and culinary traditions from Latin to Jewish to Italian. Is there anything left on the barbecue frontier? What research and writing projects are you interested in exploring next?

I’m thinking about a book on the history of barbecue, from prehistoric times to the modern day. (Also thinking about the companion TV series.) I’m also working on another novel—and this one will involve barbecue!

Rachel Jagareski