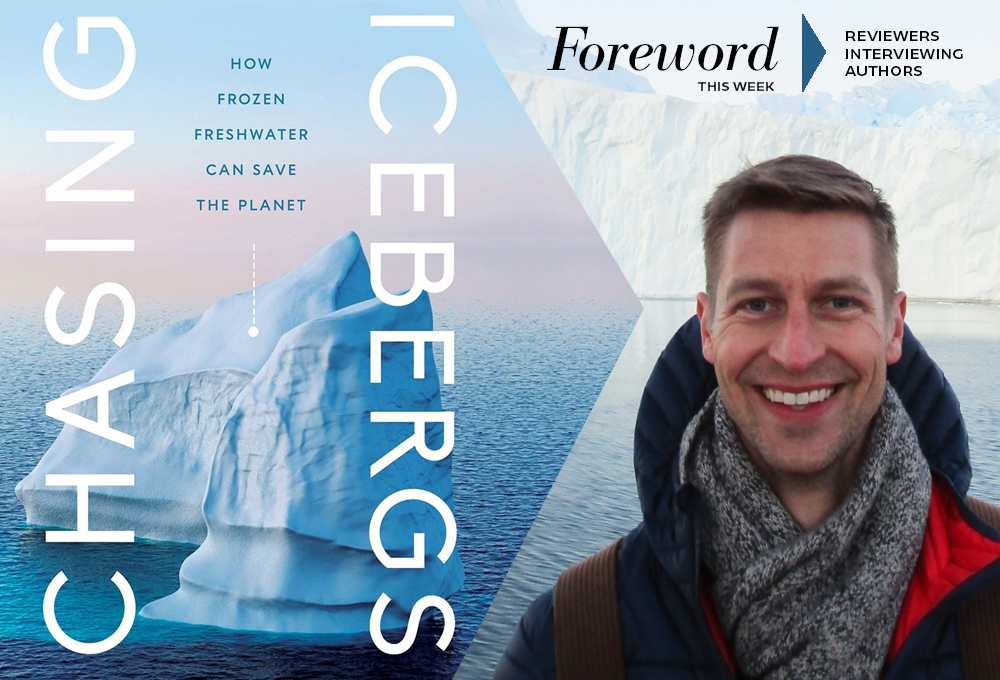

Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Matthew Birkhold, Author of Chasing Icebergs

Of late, we’ve come to expect the necessities of life to arrive shortly after the click of a mouse. Kung Pao Chicken, laundry soap, First Growth Bordeaux, birth control, you name it, at your door within a day or two.

But for many regions of the world, when it comes to life’s most vital necessity—freshwater—the Amazon/FedEx model isn’t an option. And with climate change rapidly changing weather patterns, the situation is only growing more dire for hundreds of millions of people.

But what if (don’t you love those words?) there’s a way to deliver stupendous amounts of drinking water to the shores of Africa and Asia and other places where water is scarce? Yes, that’s exactly what Matthew Birkhold is championing in Chasing Icebergs: How Frozen Freshwater Can Save the Planet.

Rebecca Foster reviewed the Pegasus Books project in Foreword‘s January/February issue, pointing out that Matthew offers “a playbook for a creative solution to an environmental quagmire.” Well, Rebecca, let’s hear more from Matthew.

Tell us a bit about how you first came across the practice of iceberg harvesting.

I first became interested in iceberg harvesting while visiting L’Anse aux Meadows, the site of an eleventh-century Viking settlement on the northernmost tip of Newfoundland, Canada. After a long day exploring the archaeological finds, my husband and I found a small bar and ordered cocktails. To our great delight, the drinks were served with gently fizzing iceberg ice. When the server explained that he harvested the ice himself, my attention instantly redirected from Vikings to law. Was it legal to capture icebergs? Who could do it? How many icebergs could a person take? As I began to research, I discovered there is a long history of iceberg harvesting but very few answers to my questions.

Globalization has been a source of many modern problems; can it solve the very issues it has caused, and/or different ones?

Globalization—and its attendant environmental costs—has unleashed planetary harms that we are still struggling to comprehend. But there is reason to hope that the responsible use of technologies to connect far-flung parts of the globe can help ameliorate some of those problems, particularly when the right trade goods are at the center of those efforts. Unlike goods like automobiles, say, which are moved around on container ships from country to country, icebergs are already in motion. Before the term “globalization” was coined, icebergs moved between borders and connected different countries and cultures. It makes perfect sense that they would be the subject of international coordination and, perhaps, the object of international trade. To minimize the deleterious environmental effects of globalization, the boldest iceberg-towing schemes purport to harness nature’s power. To the greatest extent, they plan to let icebergs move themselves, occasionally nudging them when necessary to ensure they end up in the desired location.

Does the carbon footprint seem like a reasonable measure of the environmental damage versus the potential benefits of a practice?

The potential benefit of iceberg towing is tremendous: save people dying of thirst. But this peril, of course, is directly linked to climate change. It would be a cruel irony if we allowed iceberg harvesting to actually contribute to the problem it is meant to solve by exacerbating global warming; a short-term win for more pain later.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to calculate the carbon footprint of iceberg harvesting since there are currently so many unknown variables (the size of the iceberg towed, the type of vessel towing the iceberg, the quality of its engine, how far it is traveling) and a lack of funding to study these issues.

We may learn that the carbon footprint is worth the good that harvesting can achieve. For that, we need people to invest in the effort—to invest their money, their minds, their hope. We also need people to invest in developing policies and regulations to ensure that iceberg harvesting never grows so popular that it does more harm to the planet than good.

Currently, icebergs represent a legal loophole—the legislation on water, fish, and flotsam does not apply to them. Based on your law background, how do you hope the drawing up of international regulations relating to icebergs might play out?

One of the greatest achievements of the United Nations is the development of a body of international law that helps preserve and promote international peace and security. (As a technical matter, the General Assembly deliberates and adopts multilateral treaties with the assistance of the Sixth Committee, which provides advice on substantive legal matters.) This work begins with working groups that explore complex, international legal issues. Because the idea of harvesting icebergs may seem fanciful, inspiring action may have to “trickle up” from the general public to diplomats and policymakers (otherwise thinking about something as seemingly harebrained as iceberg towing may feel like a waste of their time). If enough people become interested in icebergs—whether from an economic, humanitarian, or gustatory perspective—legal conversations will follow. This process will hopefully start with Chasing Icebergs!

One thing you’re careful to bear in mind is Indigenous rights, which you explore when you travel to Greenland. There’s a very poor global track record in terms of the exploitation of resources in ways that disadvantage Indigenous peoples. How can we ensure that access to water is controlled fairly?

Thank you for raising this issue! Indigenous stakeholders must have the opportunity to participate in conversations about iceberg harvesting. To borrow a popular analogy: they must have a seat at the table, since the current lack of regulation could be disastrous for Indigenous peoples, as has historically been the case around the globe. Right now, the dearth of regulation is an opportunity. There is no table yet. We get to decide as an international community what this table should look like and who should have seats. No one needs to be squeezed in. We can build it together. To do this, we need the help of the United Nations.

Are creative solutions like iceberg harvesting a key direction to pursue as the climate crisis accelerates?

We will have many urgent problems to tackle in the future. Some will involve trying to slow or reverse the devastating environmental consequences we’ve unleashed. Others will require us to act urgently to address acute human emergencies, like water scarcity. Creative solutions and outside-the-box thinking will be essential to solving any of these issues. As the climate crises accelerates, huge portions of the planet will run out of safe drinking water. Icebergs may be a great solution to this shortage—but whether harvesting icebergs saves the planet will depend on how we approach and regulate the practice.

Does iceberg water really taste better?

I love this question! I am not sure if I would say that iceberg water tastes “better”—after all, taste is subjective. But I can confirm that iceberg water tastes different than what I usually drink. Apart from the technical aspects of H2O, I learned from water sommeliers (such people exist!) that the story behind a water matters. As someone who grew up in landlocked Minnesota—surrounded by ice but a world away from icebergs—I initially thought the idea of drinking an iceberg seemed extraordinary. My background and inherited ideas about the Arctic made the water taste special. Now that I have more experience with iceberg water, I have a different perspective. Depending on where one lives, after all, iceberg water can be common. Exoticizing the water, I fear, could lead to thinking of the resource as a rarified product meant only for a select few. Nevertheless: I really enjoyed the premium iceberg water I have been lucky enough to sample!

Rebecca Foster