Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Thom van Dooren, Author of A World in a Shell: Snail Stories for a Time of Extinctions

Would be nice to go a week without hearing the word “extinction” mentioned alongside some other hapless animal/insect/plant facing existential doom. Alas, prepare yourself to hear it even more: the rate of species loss is “tens to hundreds of times higher than the average of the past 10 million years — and accelerating,” according to the United Nations.

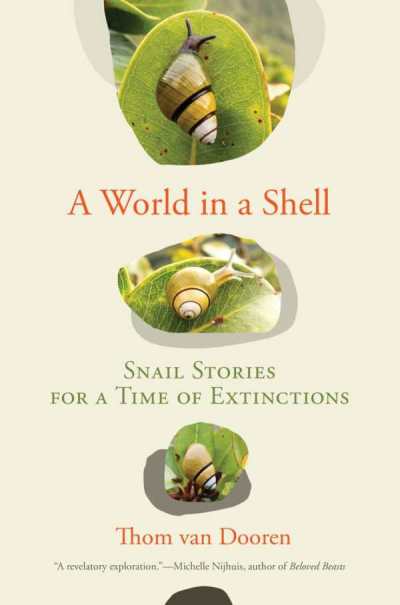

And while the big animals like white rhinos and Sumatran orangutan are sexiest to talk about at NGO fundraisers, today’s guest, Thom van Dooren, understands that every endangered or extinct species offers valuable lessons about biodiversity—so he chose to spotlight snails in A World in a Shell.

In her starred Foreword review, Rebecca Foster writes that snails are “full of surprises. They are hermaphrodites, so self-fertilization is possible. Mostly blind, they rely on chemoreception (similar to the human senses of smell and taste), and their slime serves for both spatial orientation and social interaction.” That’s Rebecca’s gentle way of chiding you for your big animal bias.

Special thanks to MIT for publishing another important work. Enjoy the interview!

You call yourself a “field philosopher”—a new term for me. What is the origin of this discipline, and what does its fusion of science and the humanities have to offer us?

At its core, field philosophy is about a commitment to exploring philosophical questions out in the world, with others. This sounds simple, but it actually has a range of important implications. In my work it has involved drawing on more anthropological field methods, including interviews and participant observation, but also taking part in the fieldwork of ecologists and other scientists. All of these insights, from the field, are then drawn into conversation with the questions and approaches of philosophy.

Bringing these methods into our thinking enables us to ask questions in ways that are more responsive to the wider world, and ultimately more responsible. There is a definite ethical dimension to field philosophy. In Isabelle Stenger’s words, it is about thinking in the presence of those who will be most affected. Doing so is partly about acknowledging the valuable ways of understanding and thinking that other people can contribute: to think with them, rather than just about them. This also means being guided to some extent by other’s questions and concerns. But, importantly, it is also about getting beyond the humans to think in the presence of snails, of birds, of forests: to take an interest in how the questions we’re asking and the stories we’re telling impact on them, and what they might have to teach us.

Finally, of course, thinking in the world, with others, requires communicating accessibly. And so, one of the other commitments of field philosophy is to find ways to share this thinking that are interesting and engaging to others—that contribute to a revitalized public discourse on these important topics. In this book I’ve sought to weave these diverse perspectives together into a series of engaging stories about snails, how they live in the world, what they mean to others, and the diverse ways in which their disappearance matters.

I live with an entomologist, so I don’t need convincing about the importance of invertebrates. Still, snails are probably a harder sell than beetles and moths. To convert remaining skeptics, how would you briefly make the case for invertebrates?

Of course, the standard answer here is to reference all the important ecological services that invertebrates provide, like pollination, decomposition, and nutrient cycling. All over the world, invertebrates are vital to the healthy functioning of the ecosystems that we cherish and depend on. But they are disappearing rapidly—with significant declines in both their abundance and their diversity. We can’t know for sure just how significant the impacts of these declines are likely to be. In part, we can’t know because of the huge gaps in our knowledge about these creatures and their roles. The vast majority of the planet’s invertebrates still haven’t been formally described and named by scientists—let alone meaningfully studied. There is a clear need to take an interest in them.

There’s definitely something to this argument about the ecological importance of invertebrates, but I don’t think it’s the only story to be told here. If we take the time to delve into their miniature worlds, invertebrates are up to all sorts of amazing things. In this book I’ve offered a glimpse into how snails perceive and learn, how they navigate and reproduce. In short, I’ve aimed to thicken our sense of who these creatures are and how they go about their lives. In this way, I hope we can begin to open up a fuller discussion about the value of these creatures in their own right, not just as vital cogs in the ecosystems we all rely on.

Your previous three books were about birds. In pivoting to write about snails, what were the challenges and continuities? (An intriguing question posed by your book, in fact, is: Can snails “fly”?)

There are all sorts of important differences between writing about birds and snails. Perhaps the biggest challenge in making this transition, though, was in how much less is known about snails. This goes for all of the aspects of their biology. There has just been so much less research on snail behavior and cognition than there has been on many of the birds—like the crows that were the focus of my last book.

This difference is also fascinatingly stark when it comes to taxonomy. When it comes to snails, taxonomic revisions are ongoing and it’s often much less clear whether or not a group of snails in fact constitute a unique species that might be classified as endangered and so protected. In this context, I learnt a lot about relatively obscure things like “triage taxonomy” (naming species as part of the effort to save them), as well as “taxonomic vandalism” (in which people basically make a mess for others to clean up by proposing potential new species and attaching their own or other’s names to them without doing the work of properly describing those species).

Your point about whether snails can fly is indeed a fascinating one, and a highly consequential one on islands like Hawai’i. This was actually the puzzle that first captured my attention. The taxonomists tell us that Hawai’i is home to more than 750 species of land snails, one of the most diverse assemblages found anywhere on earth. How did they all get out to these islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean (islands that emerged over a hotspot and have never been connected to other landmasses)? It turns out that there are a variety of possible answers to this question, but the most likely one is that they flew—perhaps on birds, or perhaps blown around up in the airstream.

Hawai’i persists in the collective imagination as a paradise—perhaps, now, a paradise lost. Why do you think it retains this metaphorical hold on us, and are such connotations useful for spurring conservation?

Postcard images of Hawai’i have done an incredible amount of damage. For the first peoples of these islands, the Kānaka Maoli, this imaginary is closely tied to historical and ongoing processes of disenfranchisement and dispossession from the land in a host of different ways. It has, of course, been core to the growth of the tourism industry, with all of its social and environmental impacts. It has played a core role in the incredible militarization of these islands. But it has also worked in more and less subtle ways on Kanaka notions of culture, identity, and gender. So paradise is far from innocent.

When it comes to the ongoing conservation crisis in Hawai’i, this collective imagination is also deeply problematic. For the most part, images of idyllic Hawaiian beaches simply ignore—and so help to erase—the incredible forests that once covered these islands and are now found only in remnant patches. Most tourists come and go from these islands without ever thinking about their many extinct and endangered birds and plants, let alone snails. But Hawai’i is one of the “extinction capitals” of the world, with nearly one-third of all of the listed endangered species in the United States being found only in the Hawaiian Islands. The first step in recognizing the huge problem in Hawai’i is asking people to think differently about these islands and their diverse ecosystems. The second step is upsetting the ahistorical notion of a paradise outside of the cares of the world, to recognize both the significant historical impacts of processes like colonization and plantation agriculture, and the present impacts of global trade, climate change, and more. These are the processes that have shaped the environment in Hawai’i and that need to be reckoned with to hold onto what is left, and they’re anything but paradisiacal.

Indigenous rights and the protection of endemic species go hand in hand. Both are threatened in places with a history of colonization and a continuing military presence. How do we go about addressing such intertwined and seemingly intractable issues?

There are many activists, scholars, writers, poets, and others finding creative ways to understand and convey these connections. I think we need to be led by Indigenous thinkers, in culturally appropriate and place-specific ways, in efforts to address the entanglement of these histories and ongoing realities.

For my part, in this book and in much of my other writing, I’ve sought to draw on the immense power of storytelling to highlight the way in which extinction is tangled up with processes of colonization, militarization, globalization, and more. I’ve been deeply inspired, for example, by the work of Mālama Mākua, a group who have successfully challenged the US Army’s destruction of a sacred valley on O’ahu, aided in no small part by the snails of that valley and the protections afforded them by the Endangered Species Act. Here, snails have been important allies in struggles for land and culture. In other times and places, the loss of snails has been a profound cultural wound. So these connections are complex and multifaceted.

We need a genre of popular “nature writing” that cuts across the imagined distinction between nature and culture to explore these tangled-up processes and help us to see our current environmental crisis as something that we are all inescapably complicit and at stake in, albeit in very unequal ways. And, as a crisis that is inseparable from a host of other ongoing crises and injustices. This close connection between culture and land (’āina) is, of course, at the heart of Kanaka life, as it is for many Indigenous peoples. So, it is no surprise that Indigenous writers are some of the most important storytellers in this space.

You write about the Hawaiian concept of “pono”—of everything being right. For someone who takes extinction as a recurring subject, it must be hard to find instances of things going right in the natural world. Where do you find hope these days?

I should start by saying that I don’t have any bold, utopic hopes when it comes to the future of Hawai’i’s snails or to so many other facets of our current environmental predicament. My hopes are saturated with ambivalence, and even mourning. They’re still hopes, though. I’m still deeply committed to working towards particular kinds of futures that are much better than what might otherwise come to pass. But they’re not hopes for a world “set to rights.” I think if we make more room for these kinds of hopes, we can find them everywhere, in all sorts of mundane, everyday labours and practices. These are the kinds of hopes I try to document and celebrate in the book. While on some level they might seem small, they often shelter all sorts of good things within themselves. And they also come together in unexpected and surprising ways, sometimes to achieve things that we would never have imagined. So, rather than being small, I prefer to think of these kinds of hopes as simply being overlooked, something that they have in common with snails.

Rebecca Foster