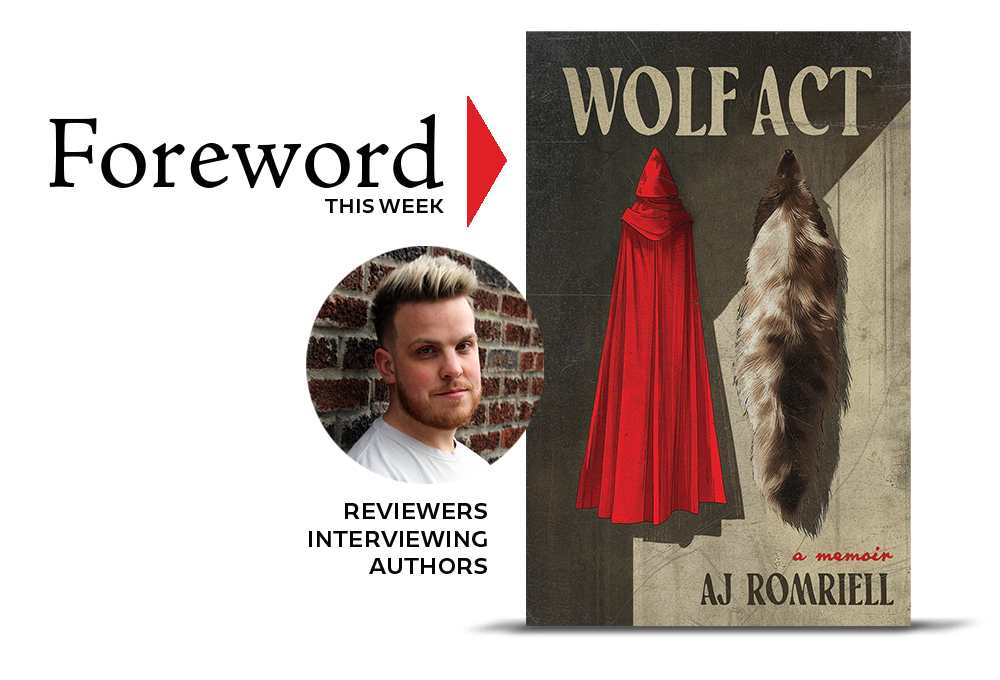

Reviewer Ryan Prado Interviews AJ Romriell, Author of Wolf Act

“The funny thing about queerness is that you never really stop coming out. Each new person I meet, every interaction, every time I stand up in front of a new class of students, I have to calculate how I’m going to embrace my whole self with them.’’ —AJ Romriell

Coming out as gay, coming out as HIV positive, coming out from under the cloak of Mormonism, coming out as a debut author—today’s guest has come far since his upbringing in Sandy, Utah. And after hearing him describe the wolf side that comes out when he feels the need, we get the sense he’s only getting started.

Romriell’s Wolf Act—it sure doesn’t seem like an act—earned a starred review from Ryan Prado in our latest issue of Foreword and never has a reviewer-author interview made more sense.

Check out the other compelling projects we covered in that Jan/Feb issue (PDF), and then pounce on your own free digital subscription to Foreword Reviews here.

I loved the way your story was informed by fairy tales and the imagery of the fabled wolf. When did the wolf motif come to you as a suitable vehicle through which to write your experiences?

I have had a fascination with wolves for as long as I can remember. They’ve always been one of my favorite animals. But the motif as it exists in the book now didn’t come until the later stages of crafting it. When I first started writing the pieces of Wolf Act, I didn’t really know it was a book I was writing. I was just telling my story of growing up in the Mormon religion and coming out as gay at nineteen. Writing was my way of processing trauma.

Then, as I finished up my first master’s degree in 2021, I decided to print out and pool together all the essays I’d written over the years. As I placed them side by side, I found patterns beginning to emerge—the most prominent motif being of the wolf. They just kept showing up. In nearly every essay, I had written something pertaining to an experience with them—acting out Little Red Riding Hood in my backyard as a kid, searching for the Balto statue in Central Park, crushing on the boy who played a wolf in our high school’s fall musical. Even my scene descriptions tended toward the animalistic: “baring my teeth” or “howling at God.” It turned out wolves had always been this lingering, unconscious part of my life. It was only after I saw the pattern that I started shaping it into a clearer metaphor—something that could help drive the narrative forward.

How do you feel the formatting of Wolf Act as a kind of screenplay, with chapters/essays written as acts, helped to home in on the bones of your story?

I remember one of the first things I ever learned about creative nonfiction was that the word “essay” has its roots in the verb “to try.” I also learned that the difference between the essayist and the biographer is that while the biographer writes about what they know, the essayist writes about what they don’t. From the very beginning of my work in creative nonfiction, I wanted to take risks. I wanted to play with form and narrative structure, even if my experiments ultimately “failed.” I wanted to try.

As I’m sure most any artist can relate to, creating art from trauma can feel so huge and impossible to wrangle. And at those times when words fail, it can be helpful to have a form that creates boundaries, even if those boundaries are later broken. It’s the relationship between form and content; the two can speak to each other in such fundamental and beautiful ways. So, when it came to the specific form of Wolf Act, I knew early on that I was interested in a loosely borrowed form of a script/screenplay. So much of what I was trying to say had its roots in how I was constantly hiding myself away, how I masked myself, how desperate I was to be someone other than who I was. Where so much of my life had felt like a costumed fabrication I crafted in order to survive, how else could I tell the story other than from the perspective of a production. And whether it was scene-work or some internal dialogue, I wanted readers to feel like they were right there in these moments with me. The form allowed me to create this sensory magic.

Your memoir offers a personable element through asking questions of the reader, even as your story is still being told. In what ways do you think your curiosity about the rearview moments you went through helped to sharpen their recollection, or hone them into something that perhaps made the writing of these often traumatizing memories a little easier?

I think there are a couple answers I could give to this, but I think what it boils down to is that writing honestly about all I went through and all I did is what allowed myself to heal. So many of the writers that have inspired me through my life are those who have shown the blunt realities of their lives, who aren’t afraid to get down and sort through the mud and muck of what they went through. Elissa Washuta. Cheryl Strayed. Carmen Maria Machado. These writers told the complexity of their own experiences, understanding that we all do good and bad and everything in between.

I’ve been hurt, and I’ve hurt others, and both of these realities exist. When I sat down to write about the dissolution of my marriage, the only way I could do so was to be honest with myself. My ex-husband hurt me, and I hurt him. We had happy times and painful times. We loved each other, and we also couldn’t stay together. All people share these kinds of complexities, and I had to sort through a lot of shame when writing about the moments and actions I still feel some shame over.

I’ve come to learn that there is no getting over trauma. The only way out is through. So, when I ask these questions of the reader, I’m asking them to understand that I am human. I’m asking them to just be there with me in the pain and joy. So often, we as people lie because we’re afraid of being held back by our honesty, that there’s something in our truths that would make people turn away. The truth can be a terrifying thing to share, so I’m looking out into the universe and asking for just a little bit of grace.

There are lots of moments in Wolf Act where your relative happiness is palpable—your pursuit of the Disney College Program and move to Orlando being perhaps the most blatant—despite the post-Mormon reconciliation and the winding road toward your coming out. How difficult was it to tap into some of those happier moments when the story still centered around these incredibly difficult memories, be they with your family’s burgeoning acceptance, or your relationships with exes?

I remember sitting in a coffee shop with my current partner as I was completing the book, and I told him about an exercise a teacher once gave me years before: to write a list of the top ten things you’re most afraid to write about, then to choose one and write about it. In the coffee shop, I made a new list with him, but I stalled out on the tenth fear. When I asked for his opinion, he told me, “Well, I would say, joy. I think you hesitate to write about joy.” And he was right.

Writing about any emotion is difficult. The human experience is so complex, so full of joy and hurt, and for a long time, I avoided writing about anything outside of the hurt. I foolishly believed that people wouldn’t care to read about joy. I thought narrative power came from never letting the reader take a breath, but that’s just not the case. It’s the ebb and flow, the push and pull. What moves me when reading is the ability to go on the emotional roller coaster of the writer’s story. Still, it took me a long time to implement that into my own writing.

I’ve learned the importance of understanding the happy and hard parts of our lives. A wonderful thing about writing this book was having the ability to look back into my history and discover (as will the reader, I hope) all the contradictions of experience, such as feeling isolated in a marriage while working every day at the most magical place on Earth.

The portions of your book where your confidence and experiences have surpassed the coming-out tier are a kind of exposé of gay culture as it exists in the 21st century. Your “Bricolage” chapter, especially, brings the politics of gay dating apps and the science of hooking up into focus. When writing those portions, was there a kind of liberation to articulate that era of your life in that way from the perspective of being in a long-term relationship?

There was an absolute feeling of liberation. There’s a strange kind of duality I’ve seen in the LGBTQ+ community over the years. Some of the kindest, most open and gracious people I know identify as part of the queer community. The people who have been most cruel to me in my adult life have been a part of the community as well. It seems obvious to say aloud, but queer people can be just as racist, sexist, transphobic, and homophobic as anyone, internalized or otherwise. Profiles on gay dating apps are full of hateful rhetoric. Guys will judge you by your weight, your height, your race, your body mass index, how hairy you are, whether you’re more masculine or feminine, etc. And what was most surprising to me was how unafraid people are to be blunt and upfront with these things. They’re normalized as “preferences” placed in the About Me sections, “No fats, no fems” being one of the most common I’ve seen, said by those wanting to meet up with the stereotypical thin, muscular, masculine man.

Go on Grindr, Scruff, or most any other gay dating app and you’ll see profiles littered with statements like “Masc for masc,” “White guys only,” and “DDF, be clean.” I took a screenshot once of one particularly nasty one that wrote, “Listen, I’m just not into old, fat, ugly people.” Many guys will ghost you the second you say something they don’t like, such as I’d prefer you use a condom or can you send a face pic? And simply going to the gay club can feel like an invitation to get groped on the dance floor.

When I first started writing about these kinds of experiences, I hadn’t planned on it being that kind of exposé. It was only after writing the “Bricolage” chapter and sharing it with some friends who weren’t a part of the gay community that I realized just how much I was revealing. They were stunned by what I shared. And when I shared it with my partner and my friends within the community, they all sympathized with the frustration. The reception pushed me to write more, and I feel like I’ve still only scratched the surface on all I have to say regarding it.

Has the publishing of this book prompted constructive conversations between yourself and those still involved with the Church of Latter-day Saints? If so, how do you navigate those conversations, considering your upbringing in the church?

It’s interesting to live at a time where Mormonism is so prevalent in pop culture. The Real Housewives of Salt Lake City showcases, in part, some of the extreme wealth and contentions of affluent Mormons and ex-Mormons; Under the Banner of Heaven illustrates the dark underbelly and toxicity of extreme Mormon fundamentalists; while The Book of Mormon musical and the new horror movie Heretic both, in very different ways, exaggerate some of the very real struggles of Mormon missionaries. All of these (and more) have pushed Mormonism into the current zeitgeist, and each have merit in conversations about the religion.

As for my own work and the kinds of conversations it will create in my life, I’m not sure yet what that will look like. I am very fortunate in that my parents and siblings have all left the religion behind; they are incredible allies who seem to never run out of support and love. As for conversations had between me and those still involved with the Church, there just haven’t been very many lately. Part of the reason, I think, is that I live in Ohio now and don’t run into members quite as often as I used to. Additionally, many Mormons I know tend to be extremely polite and avoid any kind of contention, so I don’t know if/when someone will bring up the book to me in that way. If those conversations happen (and I believe they likely will), I hope they can be productive ones. Because, while I know the kind of damage people in the religion have caused to myself and others, Wolf Act was never meant to be an attack on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was simply an exploration of what I went through while in it.

In the book’s foreword, “The Wolf Boy Overture,” you write, “I came out with a whimper, but I eventually learned to howl.” In what ways do you feel like you’re still howling, and how does that manifest for you now in terms of the way you create, be it through your writing, your photography, or your teaching?

I think we all have a journey of self-realization. We make and remake ourselves all the time, and every time we do, we have to find the courage to tell the world, “This is who I am, even if you’ll condemn me for it.” The funny thing about queerness is that you never really stop coming out. Each new person I meet, every interaction, every time I stand up in front of a new class of students, I have to calculate how I’m going to embrace my whole self with them. And while I refuse to lie anymore, I do have to consider whether I should mention my partner, tell the story of my diagnosis, explain about my religious trauma, or whatever else. I don’t think it’s easy for anyone to live life vulnerable, but my experience growing up in Mormonism, going through my divorce, contracting HIV—these things have taught me how important it is to speak up. To raise my voice. To refuse to be silenced again.

On a walk I took with a friend on the day I was diagnosed with HIV, I told her about my conversation with the doctor. My doctor had explained that medicine was good enough now that no one would ever need to know about my diagnosis if I didn’t want them to know. And I told my friend that while I understood the doctor’s words to be true, I wouldn’t let this become another “closet” I locked myself into. I was determined to write about it, to tell the story, to live proudly.

Taped on the wall behind my desk, there is a little piece of paper that reads, Speak. I keep it there as a reminder because, far too easily, I can fall back into old patterns. When I feel like I don’t belong, I start to minimize myself. But I’ve learned over the years to love not belonging because it means that the people who stay are the ones that are meant to. This is open-hand living. I try to walk through the world with my arms outstretched, palms open, letting whatever comes fall into my hands, and trusting that whatever is meant to stay will stay, and whatever is meant to fall away will fall away. To show yourself completely—the good, the bad, and everything in between—is a choice we have to make every single day.

Ryan Prado