Reviewer Sarah White Interviews Doug Stowe, Author of The Wisdom of Our Hands: Crafting, a Life

This week is all about hands so look down and ask yours if they’re happy.

What, you don’t know?

Well, do you let them play at things? Are they skilled at chopping vegetables or knitting quilts or throwing pots on a wheel or landscape watercolors or working gold and silver into innovative jewelry? Hands like to do things, with our brain’s inquisitive help. We’re not in the Jurassic anymore, Martha, note your thumbs.

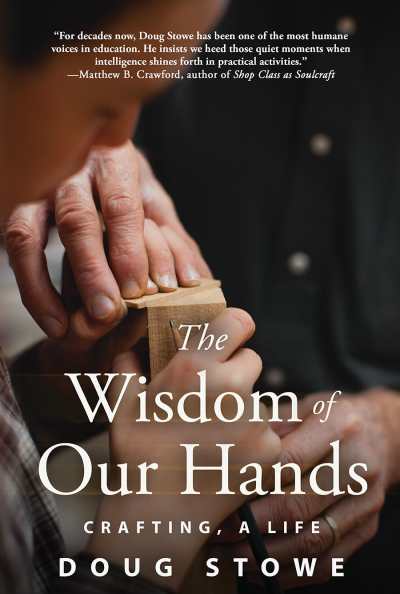

Our guest is Doug Stowe, author of The Wisdom of Our Hands, and his chosen handiwork is inlaid wooden boxes—though his designs are recognized worldwide for both innovation and skill. In the book, as well as the interview with knitter and reviewer Sarah White below, he concedes that it is easy to take our hands for granted, but says they can be a source of endless fascination if we pay attention. “Part of what I hope my book does is to help people connect more deeply and creatively with their hands and to awaken others to their power. The potential power in the hands is the same for surgeons and scientists as for knitters like you or for woodworkers like me.”

Thanks to Linden Publishing for help connecting Sarah and Doug.

What attracted you to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, and why have you stayed there all these years?

When I moved to Eureka Springs, I was looking for a place to develop skills in crafts. There was a busy downtown area with a few galleries, and a pottery. There was also a sense of magic about the place. Some people have described Eureka Springs as being “a place where misfits fit.” And many artists and craftspeople know we don’t quite fit the establishment’s square holes. We’re artists because we see something more and want to make a better place. So, this being a place where misfits fit, I found a lot of young folks here that helped establish that magic to the place—a sense of camaraderie, that kept us interested. It helped that the town is laid out pretty.

I know a sense of place is important to your work and that you focus on using local woods. How did you develop that focus and why is it important to you aesthetically and environmentally?

These days many do not know what it’s like to live in the same place for a very long time. There’s a sense of belonging when the folks at the grocery store know you by name, and when you walk into the post office to pick up a package, the postal clerk has seen you coming, knows that a package is there for you and has gone in the back to pick it up before you’ve arrived at the counter. There are feelings of kinship and belonging when the librarian stops you on the street to let you know that a new book by your favorite author has just come in and that you’re already on the list for it.

Friendships can happen overnight, but old friendships take time. Various woods, like people, can also become friends. There’s some comfort in knowing what they’ll be best for, and knowing that by caring for them, they’ll still be growing for others to use when we’re gone. If you are an avid TV watcher, and one who likes nature shows, you can end up knowing a lot about the world, and yet be stupid about the things growing in your own back yard. The environmental imperative is to think globally and act locally, and if you think globally, you know that our planet’s forests are paying a heavy price. I can drive through the mountains here and observe the state of the forests. Being a woodworker gives me insight into the value they present and acting within my local sphere gives me a stronger voice.

You’re known for making inlaid wooden boxes, and in the book you talk a bit about how you came to develop the techniques you use when making them. I enjoyed reading about that because I feel like in pursuit of skill people often try to skip over or rush through the tinkering, playing around, experimenting, and failing that is essential to creative growth. I’m not sure what the question is in there. Maybe how do you hold onto that experimental spirit as you gain competence rather than just doing things you’re comfortable with (and that pay the bills)? How can you balance that? Do you balance that?

Living in a small town of artisans gives me the opportunity to witness the value of play in others and to remind myself to go out on a limb. I’m reminded of a friend, Lizzy, in the 1970s. She was trying to learn to play the violin and made a god-awful screeching sound with it as she walked around town. I don’t know who told her to quit. It wasn’t me. But if you were raised listening to Itzhak Perlman and pick up a bow for the first time, miracles of sound will come from your instrument, but not ones you expect. You must balance your sense of where you’re growing with a healthy acceptance of where you are now and avoid self-recrimination over developments in the space between.

It’s interesting that when we pick up a musical instrument, we call it play. It should be the same thing with a hammer or saw or knitting needles or whatever. But economics can provide ample distraction and cause for anxiety. A quick lesson from my early days served me as a reminder that I must live with some degree of faith. I was down to my last ten dollars, had made a few boxes and other things, so I loaded them in my pickup truck, put in seven dollars’ worth of gas to top off the tank and drove to Memphis. There I sold an inlaid mirror to one of my sister’s neighbors for $75. With a bit of pocket money, I gassed up the truck again and drove to Nashville, where I hoped to get orders from a furniture company. Not selling a single thing, I returned home with about twice the money I had starting out, only to find upon arriving back in Eureka that friends with a gallery had been looking for me. They wanted more work and if I’d stayed home, money I needed would have arrived at a faster clip. So, it helps to have a sense of purpose, as well as a sense of the unexpected arriving when we least expect.

I’m also married to a librarian and her income was steady enough to bring us safely through tighter times.

I’m a knitter, so I appreciate the mind-hand connection you write about as being so important for everyone to engage with. How can we better connect with the “brains in our hands”? How do you encourage people to start a creative practice, whether it’s woodworking or something else?

We take the hands for granted but they can be a source of endless fascination if we pay attention. Part of what I hope my book does is to help people connect more deeply and creatively with their hands and to awaken others to their power. The potential power in the hands is the same for surgeons and scientists as for knitters like you or for woodworkers like me. And even those who consider themselves all thumbs need to establish an appreciation for skilled craftsmanship. How can one fully appreciate the wonderful objects in our great museums without better understanding the hands of those who created such work? The gifts of the hands are present regardless of what we do in our working lives, but the rest of life is made more meaningful when we learn to appreciate the culture that the hands have created and that surrounds us whether we know it or not.

The examples you use in the book are largely derived from your woodworking experience. How are these useful to those involved in other crafts?

I hope folks understand that the book is not just about woodworking. Even poets craft their work according to the senses. A poet’s material may consist of words and letters, but these, too, have sensory impact and can give shape to our surroundings. A poet’s tools may be less physical. A poet’s techniques may be more abstract. But we human beings respond deeply to the physical world, and it’s worth paying deep attention to.

Writing and teaching have been a big part of your creative life. How has that given you a different perspective on your work?

I’ve always been somewhat philosophical and inclined toward a search for deeper meaning. That requires that we find ways to interact with others beyond what we make. And as I mention in the book, teaching is part of what all artisans do, even when we’re alone in our studios, trying to craft things that will have meaning and value for others. Teaching and writing in a more formal sense have challenged me to always have new, fresher things to offer. As an example, when I was asked to do my first book, Creating Beautiful Boxes with Inlay Techniques, the acquisitions editor had seen small inlaid boxes I’d made, but to fill sixteen chapters as he wanted me to do, I had to design sixteen new boxes, each utilizing different techniques. So, teaching and writing were both instruments in making me think outside and beyond the basic box.

I know you’ve taught people of all ages woodworking skills. Do you find a difference in teaching kids versus adults? Any advice for adults trying a new skill for the first time?

Kids are easier going about the quality of their finished work. Adults are more judgmental and can be harsh on themselves when just starting out. Adults are well advised to become as little children again. I often make mistakes when teaching adults and have been told by them that they appreciate it when I make mistakes. It helps them to be more accepting of themselves when their own efforts go awry.

I think we could learn a lot about teaching children from how adults learn. Adults study and learn the things that most interest them. And they keep learning driven by intrinsic rewards that come from a sense of accomplishment. Kids are the same, and yet we make up highly convoluted and constrained systems of education that snuff out the spark that drives learning. Kids in the woodshop want to learn everything, use every tool that’s allowed them, and often think that their own creative powers are without constraint. Adults, having a more self-critical outlook, could learn a few things from that.

We’re facing a crisis in American education that I think the arts and crafts can help fix. While many artisans may not have felt that they did well in school, they’re the ones we should look to and assist in taking education in a fresh direction. The arts, nature studies, laboratory science, and other direct engagements of the hands in learning have the power to reshape the school experience. Artisans who may have felt themselves to be misfits in school have important contributions to make in education.

Sarah White