Reviewer Tanisha Rule Interviews Renée Watson, Author of Some Places More Than Others

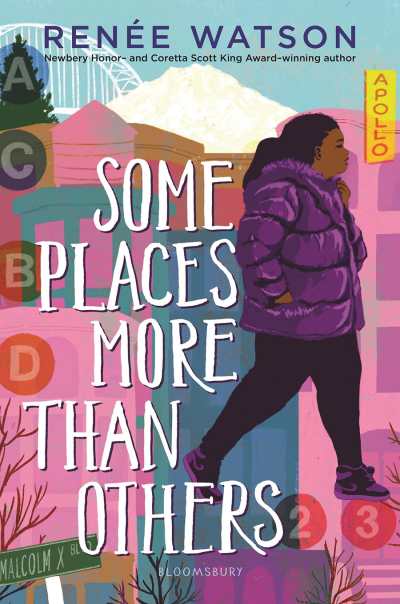

This week, we’re thrilled to spend some time with Renée Watson, A-List poet and author of books for children and young adults, including the recently released Some Places More Than Others. Most notably, she won a Newbery Honor and Coretta Scott King Award for Piecing Me Together in 2017. Watson also finds time to teach creative writing and theater in public schools.

In the main, Watson’s work features black girls and women navigating intersectional minefields of race, gender, and class. In her review for the September/October issue of Foreword Reviews, Tanisha Rule calls Some Places More Than Others “humorous and uplifting,” as it “stresses the importance of family, history, and acceptance.”

With the help of Bloomsbury, we coordinated this heartfelt email conversation between Tanisha and Renée, one that we know you’ll enjoy.

Tanisha, the stage is yours.

Some Places More Than Others deals with several difficult topics: self-identity, miscarriage, broken familial relationships, envy. Why is it important to include real-world struggles in YA fiction today?

As a writer of realistic fiction, I want to make sure the stories I create feel familiar, and that young people see the world they are living in reflected back to them. In Some Places More Than Others, readers see Amara’s loving—but also complicated—family. I think it’s important that young people see how a family can forgive and heal. Books can provide a safe space for young readers to see how characters work through hardships and challenging situations.

Discovering roots is a major theme in the book. What do you see as being the biggest risk of a person not knowing, or being interested in, one’s roots?

We risk hopelessness, we risk stagnation.

I believe knowing where you come from can give a sense of hope, pride, and determination. And when I say “where you come from” I mean this literally and spiritually, with an understanding that sometimes our families are the people we choose. Sometimes, we have to look to people we haven’t met in real life—our ancestors, activists, artists—to find commonality and inspiration. If we don’t have that, if we don’t connect to a history, I think it’s hard to have a vision for oneself. Knowing the stories of the people who came before me motivates and encourages me to take what they left me and add on, leaving something better behind for the next generation.

Which aspects of Some Places More Than Others do you hope will resonate most with young readers?

I hope readers are intrigued enough to ask questions of their own loved ones. The backmatter of the book includes prompts for creating a cultural suitcase, like the one Amara makes in the book. I’d love it if teachers actually do The Suitcase Project with students.

I also hope young readers become curious about their hometowns, that they see the places they pass everyday in a new light. Amara brings a sense of awe with her to New York that her cousins don’t have, because to them New York is such a familiar and regular place. I hope readers see their own home with new eyes.

In Harlem, your protagonist Amara benefitted from her surroundings not just because she bonded with relatives and learned more about her family’s history, but because Harlem gave her a sense of belonging in its open embrace of Black history and culture. What are your thoughts on the rapid-paced gentrification that is currently happening in Harlem? No one knows the future, but how do you think Harlem’s impact on the next gen of Black youth might be different from the type of impact Amara received if changes to the area continue at this rate?

I lived through gentrification in Portland, Oregon, where the Black community was dismantled. I hope there isn’t the same kind of push-out in Harlem.

I’m hopeful that the mainstays of Harlem will continue to exist—The Apollo, Studio Museum, The Schomburg Center. All of these spaces (and more) are pillars in the community and are an anchor that preserves Black history and culture. Because of that, I think that years from now if a girl like Amara visits Harlem, she’ll still find inspiration and be able to learn her history. This is why these kinds of spaces are so important. As neighborhoods change, we must hold on to sacred spaces so we can continue to pass down the story of who we are, where we come from.

The nonprofit you founded—I, Too, Arts Collective—has a great mission to nurture underrepresented voices in the creative arts. Your nonprofit could inspire others to start organizations geared toward legacy preservation or the arts. How did you get the idea to lease the brownstone that belonged to Langston Hughes? And what practical advice do you have for someone looking to start an arts-based nonprofit?

I was inspired to launch I, Too, Arts Collective because I wanted to see the home of Langston Hughes used as a space where the literary community could gather for writing workshops, readings, and author conversations. We build on his legacy by offering poetry intensives for youth in the summer and hope to establish a writer-in-residence program in the future.

My advice for people who want to start an arts-based nonprofit is to first ask the community what it would like to see. I had my vision, of course, but it was important for me to build something with the community not just for the community. I believe our neighbors and fellow writers and poets are invested in our programs because their feedback and suggestions help shape the programs we offer. Another piece of advice is to build a team of people who have strengths that bring balance to your own. The board of directors, staff, and volunteers of I, Too, Arts each bring assets and passion to the collective, and I could not do this work without them.

Tanisha Rule