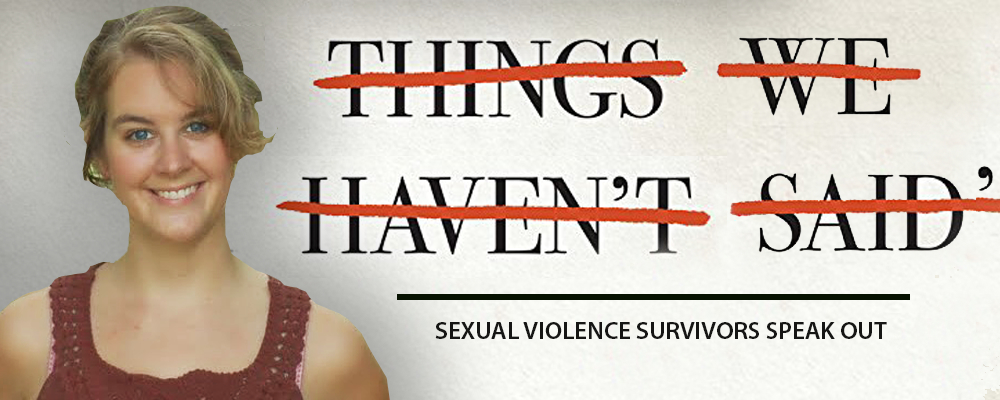

Sexual Violence Survivors Speak Out: An Interview with Erin Moulton, Editor of Things We Haven’t Said

The steady drumbeat of news stories about sexual harassment / sexual misconduct / sexual violence is both horrifying and encouraging. Women and men of all ages are finally being listened to and believed. Best of all, perpetrators are losing jobs and reputations, and, in many cases, going to jail. It’s about time, dammit.

We’re extremely pleased to introduce Erin Moulton, editor of Things We Haven’t Said: Sexual Violence Survivors Speak Out, a forthcoming collection of poems, interviews, essays, and letters written by twenty-five adults who survived sexual violence as children. A teen librarian, Moulton was inspired to orchestrate this project after realizing how few resources exist for teenage victims of sexual violence. She stepped in to fill a huge void—and we’re certain Things We Haven’t Said will offer countless young women and men a much needed dose of support, as only books can. You can preorder the book now, though it won’t be released till the end of February 2018.\

(ISBN: 978-1-942186-34-2, Zest Books)

In your intro, you discuss the incident that sparked your decision to do this book and how you came to realize how unprepared you were to discuss sexual violence with the young lady. Why do you think society as a whole avoids talking about the subject.

I think there are several different problems that perpetuate silence around this subject for children and adolescents. 1) In our culture, we already struggle to discuss sex with our teens and children, so it’s difficult to make the leap into the complexities of sexual violence. 2) Some people are so empathetic that they struggle to look at difficult, painful situations because we don’t want to immerse ourselves in that sort of pain. We remember what it was like to be that age. We tend to want to preserve innocence as long as we can. But we need to acknowledge that teens and children are victims of sexual violence. To withhold information on this subject within our homes, communities, and schools just perpetuates the problem. We can do better by seeking out information and sitting in on uncomfortable conversations. 3) The core problem may be our lack of knowledge and resources on the subject altogether. Unless you’ve studied the subject, it’s not particularly taught in schools, so unless you seek out information on your own, you lack basic knowledge. I think the antidote to this is to provide resources for teens and adults to help us grapple with this subject. One of the best resources is survivors themselves. 4) Finally, our language around this subject (consent, rape, etc.) is inconsistent depending on region. What constitutes consent in Alabama does not constitute consent in NH. If we had a universal language around the subject, I think it would go a long way in helping us navigate the conversation. Precision of language matters.

Why do you think sexual violence victims so often feel shame?

I think it’s because of the taboo nature of the subject. When we shirk away from the conversations in society, we tell survivors that they should be ashamed to speak of it. That it’s too ugly for words. That breeds isolation and shame.

On the other hand, we also see backlash in the age of the internet. For everyone cheering the voices of survivors, there are also those who shame them, outwardly. I’d love people to try to move beyond soundbites and headlines and to return to human nature’s greatest superpower: empathy. We can learn a lot through simulating the perspectives of other human beings. We need to make the effort to do so, and narrative is a great place to explore this.

What is it about books that, as you say, make them particularly “effective in showing teens that their experiences are not isolated.” And, regarding the writing process, how was it for the victims to put down their experiences down on paper, knowing they would be part of a book?

We see it over and over again: A teen feels outcast in the world and stumbles upon a character in a book who has experienced a similar trauma. The appearance of an ally, even on the page, can provide great solace to a person. That may be because the narrative process is, at its heart, a simulation of reality. In many ways, it feels like that ally, that friend on the page, is real.

As far as writing it down, these survivors showed up for the job and they were amazing. I can’t speak for them. They speak very well for themselves within the book. What I can say is that I hope it was a positive experience for them. They amazed me at how receptive they were to feedback. Many have mentioned that the experience of writing this for teens who might need it was a freeing, powerful experience.

Throughout the book, I noticed numerous words that carry loaded, powerful, provocative, though often conflicting meaning from person to person. Words like victim, survivor, shame, blame, rape, and so many others. How does the language of sexual violence affect/influence/trouble with a victim’s retelling of her/his trauma story?

Words are difficult. They seem to carry this internal battle between perception and definition. People take negative words and reclaim them for their own. Labels, particularly, carry positive or negative weight depending on who is using them. That’s one of the reasons I thought it was important to include even contradictory feelings about these words. There are no easy answers, here. Least of all in language. Let’s acknowledge the complexity. Delve deep into context. Then break it all down from there.

There is much debate about whether or how to judge the severity of different types of sexual violence—from sexual harassment and misconduct through assault and rape. Is it beneficial to the larger sexual violence conversation to discuss whether one form of abuse is worse than another?

Within Things We Haven’t Said, I wanted to expose a variety of experiences under the umbrella term sexual violence because the reader would be able to understand the complexities from assault to rape to incest, etc., and how they play out against children and adolescents. All experiences are different, all with various mental and physical health results. Instead of judging and weighing experiences against one another, I opened my ears and learned so much from all of them. I think it’s especially dangerous for teens to play that game of comparisons. “Well, there was a lot of bad touching but … he didn’t rape me. It’s not as bad as what happened to so and so. It’s ok.” To that I would say, “No, it’s not ok. What happened to you was bad. And I’m sorry. I’m sorry you have been toiling over it and I’m sorry you’ve had to spend time trying to justify that person’s actions instead of focusing on your own dreams and goals. I’m sorry you were hurt, made uncomfortable or silenced. I’m glad you are speaking now.”

What is your hope for this book? Can you see any similar projects in the future? Are you intrigued by another approach or format for addressing this topic?

I hope this book starts conversations about how sexual violence plays out, in all its many forms, against children and adolescents. I would like it to help survivors know that they are not alone. Moreover, I would like people outside of the experience to read it and gather perspective. I would like adults to read it and think about what we share with children and adolescents about the subject. I would like teachers and librarians to read it and think about what resources and information they offer in classrooms. I would like anyone who works with victims of sexual violence to read it and explore what it means to be an ally. I would like people to read it with empathy and open hearts. I would like us all to stop victim blaming, be better allies, raise our voices, and believe that the future will be better.

As far as future projects along the same lines. I really think this is a useful format to delve into complicated and stigmatized subjects. I was thinking that it might be useful to look at the opioid epidemic in a similar format. But as soon as I thought of it I began to dread it. I’d need a little break first. I want to focus on sending this project out with all the love and strength I’ve got.

Matt Sutherland