Surviving the Tudors

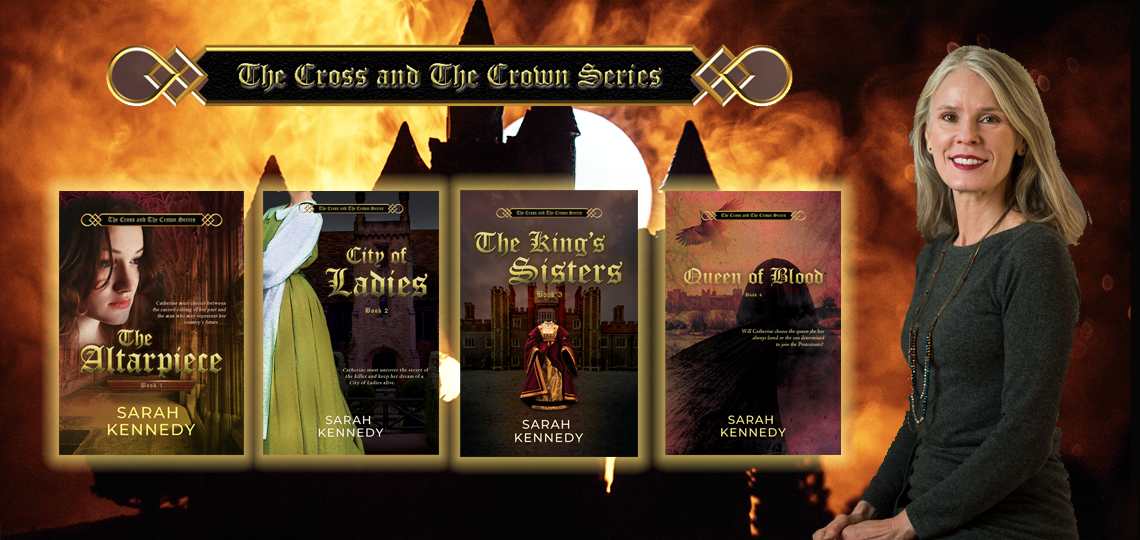

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Sarah Kennedy, Author of Queen of Blood—Book Four in The Cross and the Crown Series

Epics of historical fiction most often follow the feats and follies of major figures—kings, conquerors, masterminds, and the like—while the average Joes of the period play minor roles as minions to the plot. But for every Caesar and Sun King, the lives of millions of interesting characters go unexplored. Let’s hear it for the ordinary people.

In her compelling The Cross and the Crown series based in Tudor England, Sarah Kennedy relegates the royals and nobles to the background. Important, of course, but not integral to the story. In the interview below, she says her interest lies in “the folks whose lives weren’t recorded or celebrated, who made do with what could be had and got on with it, doing the real work of daily life.”

Capturing the lives of those commoners from five hundred years ago isn’t as straightforward as it might seem, so we were intrigued to hear about Sarah’s background and research work. Foreword’s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland jumped at the chance to discover her secrets to writing first rate historical novels.

Please set the stage for us with a primer on Tudor England politics, religious intrigue, and other factors that make it such a fascinating era in European history?

Tudor England (roughly encompassing the sixteenth century) was a time and place of enormous changes in politics and religion. As most people know, Henry VIII, once called “Defender of the Faith,” broke from Rome when he sought a divorce from his first wife, Katherine of Aragon. This break had wide-ranging consequences. Henry dissolved the Roman Catholic monasteries and convents and seized their property and goods for the crown. This had several effects.

Firstly, it upended the enclosed worlds of the religious houses, and while many of the monks had the choice to become priests in the Church of England, no such allowances were made for former nuns. These women were in a kind of limbo: not allowed to marry (though my main character, as a novice, gets permission after her betrothed greases a few palms) and often not wanted by their families. We know about some of them, and there’s been quite a lot of research into the fates of these women since I wrote my first novel, The Altarpiece, but there is still much we don’t know, especially about nuns who were not from noble families.

Secondly, Henry’s seizure of church buildings consolidated power for the monarchy. England’s monarchy was one of three great powers: the Church, the landholders, and the Crown. Once the Church’s moveable goods and the lands with their buildings were in the hands of the Crown, the power at the “top” became that much more powerful.

Thirdly, the sudden shift in belief systems shook people in England from top to bottom. This is perhaps the most important change, for me. I wonder endlessly how “ordinary” people—not royals or nobles or clergy—faced these enforced shifts in how they worshipped. Some, surely, simply did what they had to do. Others (famously Thomas More, who refused to acknowledge Henry’s Royal Supremacy of the new church) lost their lives in defense of the old religion.

Of course, the Tudor era remains an interesting one just because of all of the larger-than-life personalities involved. Henry VIII was notorious, even at the time, for his six wives, and his daughters were both queens regnant. The endless intrigues, adultery, murder, and general grandeur make the Tudor monarchs endlessly fascinating. I like a good story about them as much as anyone else, but for me as a writer the most interesting aspect of this century is how the seismic changes in religion and state power—and the fact that they were enforced by law—affected everyday people. The Crown consolidated its power, and the spy network that all of the Tudors employed made it dangerous to defy the law. And yet, people did. Any period in which a controlling government (secular or sacred) contends with its own people is going to be an interesting one, and the Tudor era is one of the most colorful examples of such a time.

How do those events influence the world we live in today?

It’s hard to say exactly how the events of sixteenth-century England affect the world we live in today. Renaissance England has come to be called the “Early Modern Period” in academic studies, however, for good reasons. Global exploration, expansions of and claims to “discovered” territory, battles over religious domination, and scientific discoveries all affected the way people saw the world. If the sun is the center of the universe and not the Earth, then are human beings really God’s special creation? If the Church can split apart, then what is the truth of Christian belief? How can one save one’s soul? Can a queen govern a country? Can she lead a church?

These questions, among many others, helped to generate an inwardness, an introspection, that often seems quite modern. Without the structures, rites, and rituals of the Roman Catholic church, a person needed to look within to determine whether their soul was fit or not. News of a “new world” raised questions of “ownership.” Global trading expanded, including the commerce in human beings; this raised questions among some thinkers about what it means to be human and whether some people are more “human” than others. Questions about the universe suggested that perhaps human beings are not the center of creation and perhaps not even very important. The plays of Shakespeare often examine such questions, and the soliloquies in Hamlet raise further questions: what is the difference between an actor and a “regular” person? Where do costumes and masks leave off to reveal the true person? Hamlet famously tells his mother, “I have that within which passeth show,” but we never find out what that interior “thing” is that makes us unique. Hamlet can feel it, though, as so many of us believe we still can.

And how does that affect the world we live in? Our notions of self—the autonomous, free self—are in many ways rooted in the sixteenth century. Our ideas about conquest and the value of science, the study of observable phenomena, about statehood and national identity, about human identity and value, are largely being generated in this period—and not only in England. These ideas were being actively engaged in many places. And those ideas have large ramifications indeed.

Queen of Blood is laced with learned descriptions of privileged domestic life in sixteenth century England, the duties of maidservants and stableboys and chicken-plucking expertise, amongst so much more. Please tell us about your research for the series?

I read a lot! I teach Early Modern literature, including Shakespeare, and many people mention these activities. I’ve also traveled extensively in Europe, and I love to visit the sites of old houses, abbeys, churches, and convents/monasteries. Docents at these sites have enormous amounts of information, but just wandering around such places can allow me to actually see how people would have lived. Where are the kitchens? How big are they? Where are the toilets and how do they flush (by which I mean how did they flush waste and garbage out of the building)? It’s fascinating just to walk around the foundations of ruins and see where the various rooms were and how they connected to each other. For example, books and papers were often stored, in religious houses, in rooms above the main room where there would be a fire. That keeps the papers upstairs nice and dry—and provides a more comfortable place to read or write.

I also have lived for long periods of time in the country, and I’ve learned how to pluck a chicken. You can’t just yank feathers out of a dry chicken unless you want to spend hours and hours digging out pin feathers. I’ve lived without electricity and I know how to wash things outdoors, and I’ve experienced the labor involved in cleaning stables. So, I imaginatively cross-reference what I know from experience with what I have observed in travel. The kitchens at Hampton Court Palace, by the way, are fabulous.

When Mary ascended the throne and restored Catholicism as the state religion, it created a sizable class of traitors—those who (secretly or not) refused to convert from their Protestant beliefs—including Robert Overton, teenaged son of your protagonist, Catherine Davies, a longtime acquaintance of the queen. Can you talk about this mother-son family dynamic, family division. Why did it appeal to you and, in your research, did you find it was common to have families divided so in England’s history of religious wars?

Family division is always a feature of big cultural shifts, and though we’ll never know how many families experienced such clashes, I wanted to highlight one of the very real effects of political and religious conflict. Catherine has always suffered over Robbie, because he’s always been a rather melancholy boy. He thought rightly that his father didn’t really love him, and since his father’s death he’s increasingly blamed his mother—and then all women—for his various miseries.

It wouldn’t be strange for him to lean toward Protestantism, as it was the religion of England throughout his childhood. The fact that his mother grew up in a convent becomes a point for him to pick at, too. He is not an especially reflective young man. He’s hot-headed and leaps to positions that undergird his personal angers. His Protestantism isn’t well thought-out, either. He just knows that he’s not Catholic and that he dislikes women, except for his sister and his mother’s old friend Ann Smith. When a woman becomes the monarch of England, he, of course, is quick to fall in with rebels against her. Mary Tudor represents for him everything that’s been wrong with England—and, unconsciously, with his life.

For me, the conflict between Catherine and her son emblematizes the larger conflicts in Europe during the sixteenth century. The family is a sort of microcosm of the larger state and religious structures, but, within the family, conflicts are often more deeply personal and tragic, simply because many people feel so strongly about their relatives. This is certainly the case for Catherine, who feels that she has somehow failed her son, but can’t quite figure out how. She loves him beyond measure, and she can still see (as many parents can) the infant, the toddler, and the child in the angry young man that her son has become. She loves him, but she doesn’t really like him very much, and that’s a difficult emotional position to be in. It allows for a personal drama that mirrors the larger dramas taking place in England and across the European continent.

It also makes me just very sad to think about the ways families rip themselves apart. Catherine sees this first-hand in the second novel of the series, City of Ladies, when she’s sent to work in the household where Mary and Elizabeth Tudor are living. Even though she has felt real hatred for Anne Boleyn and her daughter, she comes to see that the way these two girls are treated after their mothers are discarded is pitiable and, though she wouldn’t put it in these terms, personality-distorting. There was, years ago, an academic position that Renaissance parents didn’t get attached to their children, because they were so likely to die. This seems to me patently untrue, as anyone can see in the many letters, poems, and plays about the grief parents felt when their children either died or disappointed them.

What unique challenges (and perhaps, advantages) did female royalty experience in the Tudor years?

I don’t know that female royalty had any real advantages during the Tudor years. Women were often characterized as weak, emotional, and irrational, in need of a strong male hand and head to guide and control them. The social stratification of England didn’t change very much during the Tudor years, though the intellectual and theological landscapes shifted massively.

The disadvantages of being royal and female were numerous. Any female member of the royal household was generally seen as a possible trade on the marriage market. Marriages at this level were usually arranged, and it was likely only the upheavals of Henry VIII’s own matrimonial life and then the young age at which Edward VI died that allowed Mary and Elizabeth to remain unmarried.

Jane Grey, the so-called “nine-days’ queen,” wasn’t so lucky. She was married to Guildford Dudley, one of the sons of the powerful Dudley family. When she came to (or was placed onto) the throne, she was subject to the various struggles around her. Mary Tudor expected to be queen when her brother died, and she, as the eldest child of Henry VIII, had a great deal of support. But she was Catholic. Jane Grey was Protestant. Mary managed to garner enough support to take the throne and imprison Jane, but she faced almost immediate opposition in the form of the Wyatt rebellion, the event that’s at the center of my novel Queen of Blood. When this uprising was quelled, Jane and Guildford were summarily executed. Whether Jane would have had to die, if the Wyatt rebellion hadn’t occurred, we’ll never know. But Mary knew that her claim to the throne wasn’t solid as long as Jane was alive.

Mary Tudor decided to accept a husband, Philip of Spain, in hopes, surely, of bearing a child. Philip, however, was never designated king, which was a novelty for England.

When Mary died, Elizabeth was next in line. She was a young woman, and it was naturally expected that she would marry and produce heirs. For whatever reason—and there has been a vast amount of speculation about this—Elizabeth chose not to marry. This was unprecedented, and it gave her, in her childbearing years, perhaps the one advantage that a female monarch had: the promise of marriage. Elizabeth was able to suggest and pretend that she was considering this or that contender for marriage, which provided opportunities for alliance and negotiation. As she aged, this advantage faded, but by then Elizabeth’s domestic support was very strong.

Despite that support, however, Elizabeth always faced challenges to her monarchy, both foreign and home-grown. She kept a very tight, trusted group of male councilors who developed a wide spy network to control and eliminate the threats to her throne and to her life. Mary, Queen of Scots, is perhaps the most famous of these threats, and she was finally executed. Elizabeth, either genuinely or not, grieved deeply over this decision, which she claimed, genuinely or not, had been carried out against her wishes.

The threats to female royals who did not submit to the conventions of royal marriage were quite real. The fact that three royal women in the sixteenth century—Mary Tudor; Elizabeth Tudor; and Mary, Queen of Scots—refused to conform to convention is remarkable, and their colorful, dramatic lives are more reasons that the Tudor era is still so fascinating to us today.

With your vivid descriptions of how religious leaders wielded political power in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Era, your books reinforce the wisdom of our constitutional separation of church and state. Well, we certainly live in interesting times now politically. The more things change, the more they … Any comment on the current political divisions in the US and what we might learn from Tudor England?

We certainly do live in contentious times. The ease with which opinion can be circulated widely contributes to this, I’m sure. Many studies, both formal and informal, have marked how polarized our political and social discourse has become. It’s difficult for me not to extrapolate when I study the Tudors, who didn’t have social media but who did have many walls and posts where angry citizens could publicize their opinions in pamphlets and announcements. This social divide happened right across the European continent, of course, as the religious wars raged, through the sixteenth and well into the seventeenth century.

Unlike Tudor England, we now live in a democracy with constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech (within reasonable limits) and the right to choose our leaders. The average English person living under the Tudors had to be very careful about what they said in public. If they rose up against the current leader and got caught, they were likely to end up at the end of a rope, if not kneeling before an executioner with a big ax. The contentions over monarchical power and religious truth finally, in the seventeenth century, led to a bloody and protracted civil war in England, which began with the beheading of the king and caused families and friends to fight each other to the death. We usually don’t need to worry about anything worse than being put into Facebook jail for a while.

That’s all to say that we have it very good compared to Tudor England, and I wish that our rights and privileges led to more measured conversations about our very real differences. We can learn from the Tudors, and from other periods, that inflammatory rhetoric and autocratic power lead to control and censorship, to the loss of rights and lives. Centralization of authority into the hands of a single individual is dangerous. There’s not a good way to legislate this, but my comment is this: be civil in dealing with those who disagree with you, and always exercise your right to vote.

Hidden loyalties, spies around every corner, counter-intelligence, rampant suspicion, traitors uprising—this was the reality of the day. Were all of these factors how you would explain the high-level of intrigue known to the Tudor period? It seems so much more sophisticated than what we have today. But then, in light of Mary’s ruthless hangings of hundreds of rebels, the stakes were extremely high. Indeed, she earned her moniker, Queen of Blood. Has history judged her fairly?

Mary Tudor really did become ruthless in stamping out Protestantism in England, and she came to be known in later periods as “Bloody Mary,” a term I played on with the title of my fourth Tudor novel, Queen of Blood. It’s important to keep in mind that this way of viewing Mary’s reign developed after her death, in an England that had returned firmly to Protestantism. Mary Tudor as the “odd” one of the Tudors is very much part of the Tudor myth, that self-promoting set of appearances and propaganda that marks the reigns, primarily, of Henry and Elizabeth. They both worked very hard to show themselves to their people as glamorous, beautiful, talented, strong, and almost supernatural in their physical appeal.

Mary may not have been as dazzling as her father and her younger sister, but she had the power that Henry had consolidated, and she used it in the cause of restoring Catholicism to England. She executed many rebels and clergy, and she was not reluctant to use that very intricate network of spies to root out conspiracy.

The question of whether history has judged Mary Tudor fairly is a vexed one, then. I tend to think that it hasn’t, despite all we know about her willingness to hang people who disagreed with her or who threatened her. She was the first true queen regnant on the English throne, and that blazed the trail for her more famous younger sister, Elizabeth. What she did, in seizing the throne, was remarkable, and the fact that she kept it until her death is even more astonishing. When she married, she insisted that she remain the monarch of England, when it was expected that she would allow Philip of Spain to become king. She didn’t, and, for that, female monarchs have her to thank.

Mary Tudor was tough, and she had to be tough to do what she did. We should remember that.

That said, she was ruthless, and she did execute many rebels. My main character, Catherine, becomes sorely disappointed with Mary and bitterly resents the way she comes to wield power. She’s not sure that Mary can succeed in returning England to Rome. For an individual who gets on the wrong side of Mary’s wrath, I think this is completely plausible.

But did Mary Tudor wreak vengeance on her enemies any more violently than the other Tudors? I would say no, she didn’t. She knew that Protestants wanted to remove her. She knew that executing Jane Grey would create enemies for her. All Tudor monarchs (I would venture to say all monarchs of the era) signed death warrants. Edward VI was probably an exception, but only because he was a boy and he didn’t live very long.

So, I’m sure it’s accurate to say that many people in England accepted that Mary I was in fact “Bloody Mary,” and that the nation was safer with her dead. But at the same time, I do think history has rather taken the line of the Tudor myth about her too literally and could do with some correction.

You are as aware as anyone of the vast amount of other books written about this period. Why do you think you have something new to bring to the story?

My focus is on ordinary people, and that’s unusual among novels set in this period. I’m much less interested in royals and nobles than I am in the everyday women and men whose lives were thrown this way and that by the decisions of their “betters.” I’m interested in the folks whose lives weren’t recorded or celebrated, who made do with what could be had and got on with it, doing the real work of daily life. My main focus has always been on women, but I’m much less interested in famous women than I am in those women whose stories have been lost to history.

There are mountains of novels about the Tudor period. Some are quite detailed and accurate about the lives of famous people and their families; others are more whimsical and worry less about historical fact. Some are fantastical and suggest that characters are magical or connected somehow with the supernatural. I generally enjoy them all, and I’m glad that this era is so resonant with material that many different kinds of writers find inspiration in it.

The royals and nobles, for me, however, are more part of the setting than part of the story. They do appear as minor characters, and I give more space to Mary and Elizabeth Tudor when they’re young. The third novel, The King’s Sisters, makes use of Anne of Cleves’s life after her divorce from Henry, but, again, she’s not really the central character. Taking my cue from Shakespeare, I’m less concerned with the day-to-day record of where exactly a historical person was and more interested in how that “real” personality might interact with one of my fictional characters, though I try not to maul the historical record too badly.

My story is about a woman who has some advantages but who always feels a little separated from the standards of her day. I made her a novice to begin the story, but I put her in an out-of-the-way village in Yorkshire. She’s not in a big, important convent, and she’s not part of a noble family. She’s the daughter of a nun and a priest, which becomes in part a source of shame for her. Once she gets married, Catherine never feels quite at home as the mistress of a big house. She makes mistakes. She likes to be out getting dirty in the garden. She wants to nurse her own children. She has a fling with another man while her first husband is still alive. She later gets pregnant out of wedlock and then marries the baby’s father though she has doubts about whether she wants the child—or the husband.

My Catherine is unique in that she isn’t noble or royal or famous. She’s an intelligent woman trying to find her way in a world that keeps changing around her. She works, for a while, in the household where Mary and Elizabeth Tudor are, and she feels an enormous sorrow at what Mary has suffered. But then she comes to sympathize with Elizabeth, as well. So, she’s caught between the Catholicism of her youth and the Protestantism of her adulthood, and she doesn’t feel entirely at home in either church. She really just wants to have some freedom to use her mind and her hands. She wants to be surrounded by women that she trusts.

She’s not that different from other ordinary people, and she’s not that different from us, and those are the people of the Tudor era that catch my imagination the most. The famous Tudors and the nobles, and all of their families, are fascinating, and I love to read about them, but that’s not where my writerly interest lies. I want to bring to life the kind of person who has been invisible because they’ve wrongly been considered unimportant.

Queen of Blood is book number four in The Cross and the Crown series, and you’re currently at work on number five. Please tell us about the breadth and reach of the story, and what we have to look forward to in the next book?

Catherine finally gets to travel out of England in book five, which begins with the death of Mary Tudor and the ascension of Elizabeth I. This final novel doesn’t end with the end of my main character’s life; she’s definitely still casting a shadow at the end of it. This novel is made up of quests, and it emphasizes how the notion of quest might be different for a woman than it would be for a man. Catherine travels to the continent, and though I don’t want to give away the plot details, she finds more—and less—than she expects. A woman in this period rarely traveled alone, so she’ll have people around her who care about her.

I want, with this last novel, to take on some of the issues of the day beyond England. The global trade is well underway on the Continent, and though it’s gotten started in England, that island was usually behind the times compared to Continental Europe. Catherine has high hopes at the beginning of her journey that she will quickly prevail and return home successful. But she encounters more difficulties than she plans on, and she discovers that triumphal returns may be in the stars for the queens she’s admired and sometimes feared, but for an everyday woman like her, who is aging and somewhat tired, things may be entirely different. That’s all I’ll say, but I hope readers enjoy going on a journey with Catherine!

Matt Sutherland