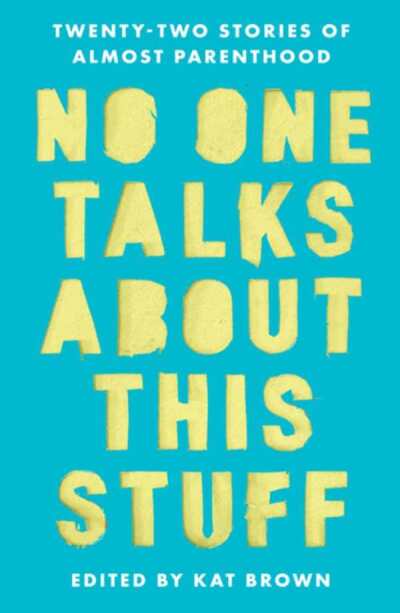

Talking to Kat Brown about No One Talks about This Stuff: Twenty-Stories of Almost Parenthood

You count on us to answer questions you didn’t know you have, so you will be pleased to hear that Ivan Andreevich Krylov came up with the “elephant in the room” phrase in an 1814 fable named The Inquisitive Man. You’re welcome.

Yes, unacknowledged elephants are top of mind but only because today’s interview caused us to reflect on conversations with friends and family when something uncomfortable—death of a spouse, cancer diagnosis, a recent breakup—was on everyone’s mind but no one had the nerve to bring it up. Even more fraught was running into a sexual assault survivor, which elephanted a flurry of guilt, emotion, and sex taboo to avoid talking about—causing the young woman even more isolation and shame than she was already feeling. We will try to do better next time. And we encourage you to make an effort to acknowledge those elephants. Be empathetic. Listen. Just be there.

We’re immensely thankful Rebecca Foster didn’t shy away from asking Kat Brown about infertility, childlessness, miscarriage, and the other sensitive topics covered in Kat’s No One Talks about This Stuff, which earned a flattering review from Rebecca in Foreword’s July/August issue.

Go ahead, Rebecca, ask Kat.

As children we might have a magical, romantic idea of what becoming a parent will be like. Instead, nowadays, it can be a very medicalized process. How can we balance the clinical and emotional realities when writing about “almost parenthood?”

Thanks to being an addictive reader, I grew up with very romanticised ideas about love but not parenting. There was a whopping great recession when I was small, and I saw how difficult things were for my own parents—and this was as a middle-class family. I spent my twenties terrified of falling pregnant and my thirties not able to. My schools taught me very little about the reality of sex and how bodies work beyond the fear they instilled in us all of even looking at the opposite sex lest we ruin our lives. Even now, what we know about pregnancy and childbirth can feel utterly bewildering. Teaching children that families come in all shapes and sizes is a great start to raising a generation that feels included and seen, and is prepared for what might come down the line. I really love the way schools celebrate carers and grandparents along with parents for this reason.

I was fascinated by the concept of disenfranchised grief—hidden grief that doesn’t get acknowledged by society. Is the situation getting better? (Thinking of things like free commemorative photography of stillborn babies, and urns or caskets for miscarriages.)

So much of this stuff is out there if you look, but in the moment—what is there really? What do we know instinctively to reach for? In her book All the Living and the Dead, my friend Hayley Campbell wrote some breathtaking portraits of bereavement midwives who help deliver stillborn babies. I would have had no idea they existed otherwise because I hadn’t needed their help.

Social media and changing attitudes mean that we can now talk and hear about what isn’t considered “nice” and gather support from friends and family that simply wasn’t possible years ago. Pain needs to be recognised in order for you to set it free. In the UK, the government has recently introduced baby loss certificates for anyone who has gone through a miscarriage. It’s thanks to the campaigning work of Zoe Clark-Coates, who has also introduced free and secular goodbye ceremonies in beautiful British churches for anyone who has lost a baby—even if they didn’t have the chance to conceive. This sort of inclusion and thoughtfulness is absolutely wonderful. I’ve been to one of the services with my husband, in a stunning Oxford cathedral, and it was really meaningful.

However did you go about narrowing down the pool of essay submissions while portraying the breadth of people’s experiences and presenting an intersectional view?

We hear ourselves in other people. We find ourselves in stories that, on the surface, have nothing to do with our own. There is a really lovely saying in recovery circles: “Listen to the similarities and not the differences in the sharing which follows.” You could find my long-lost identical twin, who was somehow also childless, yet we would probably think our stories were completely different.

Crowdfunding meant that not every writer needed to be a celebrity to be included, and I wanted to include as wide a range of voices and experiences as possible, with a bit of what else was going on in their lives at the same time as baby loss. Everyone could write well—that was never a problem! My first editor, Fiona Lensvelt, and I first collaborated on getting fifteen stories together. I was then approached by a donor who gave an extra pledge so that we could have seven further stories.

I opened up to public submission with clear guidelines that writers needed to be well on in their grieving—being edited is no place for processing trauma! I was staggered to receive more than two hundred submissions from around the world, and was very grateful that people trusted me with their stories, which enabled us to carry stories from Jewish and trans women, genderqueer people, fathers going through loss, and their own very specific intersections of race, gender, religion, sexuality, mental health, and living.

Choosing who would contribute was horrendous, as everyone is always so clear and generous when sharing their own story. There could be a second book, a third, a fourth. The world is filled with stories that demand to be shared, read, and heard.

Your own contribution prints excerpts of entries taken from five years of your phone diary. Why did this reflect your journey better than a retrospective written later?

I wanted to be as vulnerable as the reader. I didn’t want to come to anyone from a lofty “editor” chair with all my edges rubbed smooth or made palatable. My brain, my mind, and my heart were all over the place when I was going through this, and I wanted that to be reflected along with my slow healing.

Retrospectives are some of my favourite types of writing. You can weave your story into something cohesive and whole. I did that for my introduction to the book, where I also brought in a fair bit of my own story: failed IVF due to immature eggs and a non-diagnosis of unexplained infertility leading to childlessness (and two cats and a dog). Doing something different was my sneaky prerogative.

Your other book recounts being diagnosed with ADHD as an adult. Do you feel like that was a parallel experience to infertility—misunderstood, veiled in secrecy or shame?

Yes, totally! Accessing treatment can similarly involve long waiting times and large amounts of money. Undiagnosed ADHD played a big part in how I responded to the IVF not working: I quit my stable job on a whim, and after doing a lot of work looking into adoption, I felt instead like I really needed time to recover from the years of trying to conceive. I didn’t feel steady enough to go through such a massive process—and I was worried that I might be seen as an unsafe parent because my brain seemed a bit odd. I was deeply comforted after my diagnosis when a therapist reassured me that plenty of people with ADHD are excellent birth and adoptive parents (and I interviewed plenty of them for my other book, which became another source of healing).

What was your experience of working with Unbound (a crowdfunding publisher)? Did you initially worry that only relatives and friends of contributors would pledge?

It was probably totally deranged of me, given the target was £20,000, but I was never worried about getting the book funded. I had total confidence in the need for this book, and I was enthused enough about it to keep people interested. I also knew from when I ran the London Marathon in 2014 that you need way more than your circle to reach funding targets. It was more important for me to reach people who would truly benefit from this book existing in the world and to get them and other readers excited about it than to take a pot around my family and friends (who I also didn’t want to potentially guilt trip about something so sensitive).

While you and the other essayists may have felt that “No one talks about this stuff…”, some do have the courage to. Can you give examples of role models and admired authors who have spoken out publicly about their struggles or published work that was helpful or cathartic for you?

The name feels almost out of date now, which is wonderful. Then I wonder whether it’s just that I’m “in” this world, so I notice it more. So many people do talk about this stuff—but you have to look for it. Chances are that nobody in your family is talking about it, and perhaps not in your inner circle. “This stuff” is sad and upsetting, and you want people to feel like nothing bad will ever happen to them. For a long time, it felt like the only people “allowed” to speak were celebrities or people who had a living child and so wouldn’t bring the mood down too low. Social media and podcasts have evened the playing field.

Kate Bowler’s intensely thoughtful and very funny podcast, Everything Happens, and her accompanying books have guided me through the last five years. Bowler’s own fertility was affected by stage IV cancer treatment, meaning she couldn’t further expand her family, and the array of guests she has had on her show to talk about grief and living after unthinkable loss has brought me huge comfort, along with books, posts, and newsletters by Mari Andrew, Heather Havrilevsky, and Chanel Miller. Then the hysterically funny and deeply real Chrissy Teigen has done more for awareness and understanding than I could ever hope to, through her Twitter and Instagram.

Anyone who speaks about “this stuff” publicly helps, whether they’re an icon or a private person on Instagram. I’m very lucky that some of them have written for this book! Stella Duffy, who has weaved it in her extraordinary fiction for years; the author and activist Jody Day and her book Living the Life Unexpected, which was my absolute crutch while coming to terms with never having my own children; Sophia Money-Coutts, who did a brilliant podcast, Freezing Time, in between her wildly successful journalism and novels. I’ve dedicated the book to the British novelist Jilly Cooper, who, for years, was the only blockbuster author I knew to put her own infertility and loss into her glamorous main characters.

How lucky we are to live in a time where (some) people feel comfortable sharing their stories—and where we can go to a bookstore and find just what we need to help get us through.

Rebecca Foster