The Cure for Ignorance About Islam: Facing the Ugly Truth About All Beliefs

“You don’t know everything, Howard. You think you know a lot, but you don’t know everything.” I was nineteen years old, so a more accurate statement might have been that I didn’t know anything. The topic was Islam, and this spot-on criticism was one of the first things Lamya ever said to me at the beginning of a personal and intellectual relationship that would change my life.

The year was 1984 and I was a student journalist at Wayne State University in Detroit. I had just written a story for the student newspaper about a Muslim student group that was peddling copies of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion at a book sale. My coverage of the sale of this book, a notorious anti-Semitic forgery, would be my first trip down the rabbit hole of religious misinformation and conflict, and I would emerge better prepared for a career as a journalist and as a writer more equipped to understand nuance. I am thinking of this thirty years later because all nuance is being lost in discussions about Islam today.

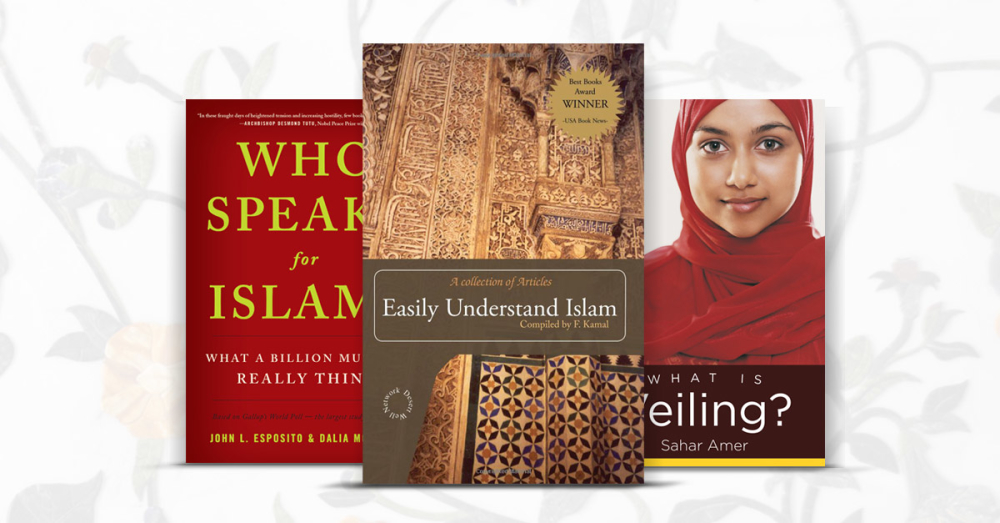

Understanding Islam: 8 Books Introduce a Diverse World Tradition

I don’t pretend to have the answer to the ugly anti-Muslim hatred—borne of fear, ignorance, and selective listening—raging across the country. But I do know that some of the solution is about facing the truth and perceptions regarding one’s own beliefs and their almost chemical reaction with the beliefs of others. The truth is not pretty—not the ones about yourself nor the ones about others. At the age of nineteen, I was a Jew from the suburbs who knew absolutely nothing about Islam except for what I absorbed through my own culture and heritage. Yet I was fortunate that, in college, I ran smack into the stone wall of my own ignorance and slowly began carving a tunnel.

I have my Palestinian friend, Lamya, to thank for that, along with my nemeses among the Muslim students who made it their mission to publicly denounce me at every turn. They all told me that I didn’t know everything. Not that what they told me was the truth. But I learned how the other thinks and perceives of the truth.

“We are Semites ourselves,” said Mohammed, speaking to me in a cramped office at the Student Center during our interview for my Protocols story. “How can we be anti-Semitic?” It was the first taste of an argument that would be fed to me throughout my college life, and that still tastes funny today—that anti-Jewish sentiment on campus is, in fact, not anti-Jewish, it’s anti-Zionist. But, like an African American at a Klan rally or a woman passing by a construction site, silence does not mean you don’t feel what you feel what you feel.

“It doesn’t matter if the Protocols are fiction. Maybe they are, maybe they aren’t,” said Mohammed’s friend, Khalil, animated and hovering over me as I remained seated. “But you cannot deny that many of the prophecies in this book have come true. Jews run the financial systems.”

I dutifully wrote a story for the school newspaper about the selling of the Protocols, quoting the head of campus chapter of Hillel denouncing it and quoting the Muslim students about their right to sell what they wanted. From my limited knowledge and perspective at the time, there was nothing more I could do but a “he said, he said” story, although the Muslim students were not happy at all with what I wrote. They sent in angry letters to the editor about the Protocols coverage, and about some pro-Israel pieces I had written. I was targeted. Specifically. I was denounced repeatedly during my college years. At one time, just about every Muslim student on campus showed up to a meeting denouncing me when I was up for the position of editor-in-chief.

Had my college experience been that, and only that, it likely would have hardened my own position about what all Muslims believe and how they handle contrary information. I was fortunate, then, that I had Lamya, my Palestinian friend who eventually became more than my friend. We were inseparable for a few years. Ten years my senior, she had escaped an abusive marriage, along with her ten-year-old daughter, and had gone back to school to study English and journalism. She knew first-hand the violent side of her own culture, but was also proudly Palestinian.

Together, we told each other what the other did not know. We arranged Jewish-Muslim talks on campus, we discussed books. Lamya helped me move beyond my Philip Roth and Saul Bellow phase, great writers with whom I had an inborn cultural understanding. It was time to move on. Lamya introduced me to the Qur’an, which I read for the first time at her home in Dearborn, Michigan. The stories were familiar. There’s the story of Noah. There’s the story of Abraham. All there. All told slightly differently. The Qur’an, itself, I noticed, was not inherently anti-Semitic (or, anti-Jewish, if you allow Mohammad and Khalil’s point that we are all Semites), but the commentary in the footnotes that began “The Jews, in their arrogance, would say …” left me a bit cold.

Yet, through Lamya, I was introduced to the full breadth of Muslim thought, which seemed to me much like Jewish thought—you get two of us together, you get three opinions. The spirit of discussion, of dialogue, of cultural repartee, was a refreshing counterpoint to the angry letters, the denouncements, I received at the newspaper and at student meetings. It is one thing to sit and write denouncements, to throw slogans, to step up to a microphone against a Jew or a Muslim, but go ahead and debate each other, read each other’s books, tell each other jokes, and there will come something more tangible and human.

My relationship with Lamya ended toward the end of my college days, and it ended violently due to members of her family who, let’s say, did not understand the subtleties of our relationship. But that is a story for another day.

I am thinking of her these days, though, as I see the same pattern of denouncement and fear based on willful ignorance. What I went through all those years ago was about me being forced to face both the truth and the perception about my own beliefs and the beliefs of others. Truth may not be pretty when its light shines everywhere, including uncomfortable places. But we can rise above our own upbringing and culture to enter a more-nuanced world.

The story of humanity is the story of culture and faith. We can choose the easy way of sitting behind our computers to denounce or we can engage in conversations to find the truth, no matter how ugly, and rise above it together.

Howard Lovy is executive editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow him on Twitter @Howard_Lovy

Howard Lovy