The glittering world of the Ziegfeld Follies comes alive in this mesmerizing book

Reviewer Karen Rigby Interviews Susanne Dunlap, Author of The Adored One

Without a doubt the entertainment industry would have been a prettier place if the #MeToo movement had gained a foothold in the early days of both Broadway and Hollywood. Ambition, greed, misogyny, power imbalance, and vile behavior were the law of that dreams-come-true land, and, as usual, women took the brunt of it.

Even so, they were exciting times and Susanne Dunlap chose two of the most fascinating characters of the era—Florenz Ziegfeld and Lillian Lorraine—to base her thrilling historical novel, The Adored One. After reading her glowing Clarion review, we asked Karen Rigby to connect with Susanne for an in-depth conversation about early Broadway, the Ziegfeld Follies, Lillian’s gutsiness, and the other reasons she was drawn to the story.

The Adored One explores turn of the century Broadway. What drew you to this side of New York history? Any particular surprises in the archives?

The first decade of the 20th century has always intrigued me. It’s a time of such forward momentum in industry and commerce, and a time of change in the roles of women. As a pianist and music historian, I am perennially interested in what’s going on in the arts at any given time, and then as now, New York was the hub of creativity.

As I researched earlier days in a city I know well—having lived there three different times in my life—I was constantly surprised both by how much has changed and how much has stayed the same. Digging into the history of Broadway and Ziegfeld turns up many familiar landmarks, places that still exist today although often in an altered state, or a different location.

One of the biggest surprises of my research was discovering the open-air rooftop theaters, where productions were staged during the summertime. No air conditioning, of course, so they took advantage of whatever breeze they could find to lure the public in for entertainment. It was the perfect setting for the Ziegfeld Follies brand, and without these opportunities, the Follies may never have existed.

Music, costuming, and the intricacies of the stage are vivid—would you comment about your relationship (if any) to the theater?

I was never really a theater kid—although I acted in high school productions. My backstage experience stems largely from having been a ballet mom to two talented dancer daughters, and being handy with a needle. I loved working in costume shops and would help out when I could, or even create costumes for some productions. I witnessed first hand the backstage business, the tension during a performance, and the egos and personalities involved. It was easy for me to imagine some of that transplanted to Broadway in the early 1900s. And Ziegfeld was a costume guy: he spent more on costumes and sets than many Broadway producers of his day spent on entire productions.

I also had a brief spell as a vintage clothing and textile dealer, which has always given me an intense interest in fashion as well as costume.

As far as the music goes, it was tremendous fun to find the lists of songs in each of the follies, and locate some of the sheet music so I could actually play them myself. I’ve worked for an opera company as well as getting my PhD in music history (with a concentration in opera), so the mechanics of singing are familiar to me—even though I’m a pianist, not a singer. And having performed on stage myself, digging into what that felt like, nerves and all, and translating it to how Lillian might have felt was a welcome challenge.

Lillian is inspired by a striking, real woman, and Ziegfeld is a complicated visionary. Their relationship, though, isn’t a May-December romance: it’s rife with #metoo power dynamics. How did you go about creating Lillian’s simultaneous naivete and precocity?

This was hard to do. I had to work to put myself in her mind (or what I imagined of her mind), as a girl who had been exposed to too much too early in her life, made to act like an adult when she was still very much a child, and put into a position where she had to survive in a somewhat hostile world. Lillian isn’t at all like me! I’m an introverted intellectual who doesn’t drink, never smoked, and has never done drugs—which is pretty much the opposite of Lillian!

So I really had to imagine someone completely different from me. I had to comb my past for people I knew who were more like her, and ask myself all the time not what I would have done, how I would have responded in her situation, but to put myself back in that time where different things were expected of girls like Lillian. It was a challenge to imagine how she might have walked that tightrope between innocence and experience, what she knew or didn’t know, how people responded to her. I tried to envision the conflict between having that life and being so young.

But what really helped was that in The Adored One, Lillian is talking about her life in retrospect, with the wisdom of hindsight and self-knowledge. I think it would have been much harder if I hadn’t framed the story as a memoir. Having her look back allowed me to enable her to put her relationship with Ziegfeld in perspective, to gain some closure, in a way. Or at least, overlay some justification for her actions at the time.

Were there concerns or particular challenges about portraying their connection?

In a word, yes. How could it not be tricky to explore a relationship between a teenager and a forty-year-old? I tried not to portray Lillian as a victim. I didn’t want to impose our modern sensibilities on what people would have thought at the time. I chose to let the reader make that connection based on what actually happened and the world itself. And at the same time, I didn’t want Ziegfeld to come across as a lecherous old man. He was probably no more susceptible to taking advantage of his power in the theater than anyone else was at the time. Plus, I think he genuinely loved Lillian. He certainly took care of her when he could. Why else would he have asked her to marry him four times?

With historical characters, who may or may not be familiar to the reader, is there any special consideration about portraying the “truth” of their lives, while doing what is necessary for the novel? Does it amplify a writer’s responsibility? Or is it best not to overthink this?

This is a great question. What I always say to the writers I coach is that the story comes first. Without a great story, you don’t have a novel. And that means the protagonist has to have perceivable wants and needs and obstacles and struggle to overcome them. Those are the things that can be hard to discover in the actual history, so it’s a balancing act between what you know and what you invent. You have to read between the lines, and be willing to invent for the sake of the story. You have to dig below the “what happened” and “how” to get to the “why.” And that why might not exist anywhere else in history, but you have to go there for the sake of the story.

And, in all honesty, even in a biographical novel, as soon as you are in your historical protagonist’s head, you are inventing. As soon as you create scenes with dialogue, you are inventing. Staying true to the character you believe that protagonist to be requires scrupulous research on the part of an author of historical fiction. But ultimately, like all history, it’s an interpretation.

Fiction is the noun. Historical is the modifier.

Amid the glamour onstage, hardships backstage, and scandals involving chorines, the novel’s mother-daughter relationship stands out. Could you speak further about the poignant tension and underspoken love between Lillian and her mother?

It’s always a challenge to portray a mother-daughter relationship—at least for me! In some ways, having been in the ballet world and witnessed the antics and machinations of umpteen dance moms, it wasn’t that hard to imagine the specific relationship of Lillian and her mother. The difference was that the underlying trauma (which is not historically based that I could discover) of the abusive father/husband is what I imagined pushed Mary Anne to be emotionally unavailable and to force her daughter to succeed at all costs. And yet, to dedicate your entire life to a child’s career, at the expense of your own fulfillment as a woman, is a gesture of great love—and unimaginable pressure on the child.

I think that my Lillian struggled against her mother’s control, but when it was no longer there, she became rootless, unhinged. That all played into her twisted relationship with Ziegfeld, I think. And perhaps—because he in some ways stepped into her mother’s shoes—it was the reason she wouldn’t tie herself to him.

The story is told in retrospective, as a memorial service prompts Lillian to consider her past. When did you land on this point of view, and the general structure for the book?

So interesting that you ask that! In fact, I wrote the very beginning of the book last of all, after several different versions that started in different places, some of them digging back into her childhood in San Francisco. That opening really helped me discover Lillian’s voice and her perspective about her life. It also made it easier, in a way, to deal with some of the difficult material, as I said.

Because the book draws from Lillian’s biographical details, the conclusion to her story is in some sense knowable. Still, when you were inhabiting her voice, were there any turns that you hadn’t expected?

The biggest unexpected turn as I was writing Lillian, trying to get inside her mind, was that I figured out that above all else, she valued friendship. Her romantic relationships were disastrous, but even through some rough patches, she always stayed true to her friends. It made sense to me. She’d been denied a childhood, where friendships are most often established. In a way, as an adult, she was constantly trying to create that friend community she didn’t have as a child. Even Ziegfeld, who she rejected multiple times, stayed friendly with her to the point of paying for her medical care after she broke her neck in an accident and was in a hospital bed for months.

Fortune, its blessings, and its fallout are a strong theme; love and relationships are, too. Are there other subtle facets of the novel that you’d like to highlight for readers?

I think the one thing we haven’t talked about is how the world of entertainment, the theater, was both a passion and a powerful economic engine. Theater, showmanship, was in Ziegfeld’s blood, yet he almost never made a lot of money on his productions. In some cases, more money was made on sheet music sales than on tickets.

At the same time, Lillian herself doesn’t seem to have had that burning ambition as an artist, or been very mercenary. She didn’t have an exaggerated sense of her abilities, and perhaps because her mother made sure to point out her faults, she is clear-eyed about how far she could go on stage. She exploits her own beauty, but it doesn’t seem to blind her to how fleeting it is. The fact that she pushed herself to do other things—writing and directing films, albeit not very successfully—and was perfectly willing to make her way in whatever venue presented itself, proves that she was, in essence, more than just a pretty face.

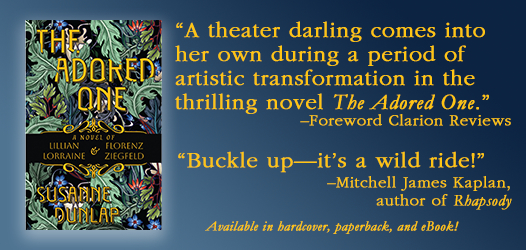

THE ADORED ONE

A NOVEL OF LILLIAN LORRAINE AND FLORENZ ZIEGFELD

Atmosphere Press (Oct 17, 2023)

Clarion Rating: 4 out of 5

A theater darling comes into her own during a period of artistic transformation in the thrilling novel The Adored One.

In Susanne Dunlap’s mesmerizing historical novel The Adored One, a chorus girl comes of age under the watchful eye of a theater impresario.

Lillian is fourteen when her calculating mother ushers her from San Francisco to New York City. Though she is told that she only has her looks to bank on, Lillian is smarter than she’s given credit for. She looks for opportunities on Broadway and models for artists and photographers, making connections she can rely on later.

Recounted in hindsight from Lillian’s wiser, wry, and worldly adult perspective, this is a potent and emotional tale. Lillian recalls being bright and eager in her youth, dreaming of stardom though she’d already experienced harm before arriving in New York City. And she pays homage to early twentieth-century New York itself with details about its horses, automobiles, ragtime culture, and classic hotels. She’s there to witness the city’s changing society.

Here, Lillian is positioned as someone who helped to lead the way in the arts during this transformative period––a precarious, sometimes envied position. She shares glimpses of the era’s scandals, including the murder of an architect by the husband of a fellow chorus girl. Excitement and danger surround her; she is reckless in her passion. But self-awareness and savvy buoy her somewhat—until Florenz Ziegfeld takes an interest in her.

Florenz is married and over twice Lillian’s age. A Pygmalion figure, he is instrumental to Lillian’s rise, but he’s an elusive lead character. He orchestrates roles for Lillian; he also turns cold. His temperamental attentions confuse Lillian, who appreciates being favored by him but also experiences isolation from the rest of the cast as a result of this attention. In hindsight, she reflects on what might have been in their business relationship; her takeaways are candid ones. The result is a tangled central relationship—one attended to with delicate balance, neither excusing nor pillorying Florenz while also honoring the delicacy of Lillian’s childhood emotions.

Lillian’s theater life is depicted in its full hedonism, with instances of substance abuse and being fêted in public included. The narrative is calibrated with hard truths about Lillian’s choices, too: in the pursuit of stardom, she lies about her age and keeps her mother hidden; her relationship with her mother is complicated by feelings of indebtedness and expectations. However, amid this excitement comes increasing outside speculation regarding Lillian’s relationship with Florenz; some momentum is lost in the process. And a late, impulsive decision related to a handsome passerby results in a distracting (if biographically accurate) narrative digression—an event that is covered in terms that are somewhat at odds with the arresting explorations of the ingenue’s exploits that precede it.

In the intricate historical novel The Adored One, a memorable star of the stage reminisces on her past relationships and her rise in fortunes.

Karen Rigby