"The most realistic yet least depressing end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it guide out there."

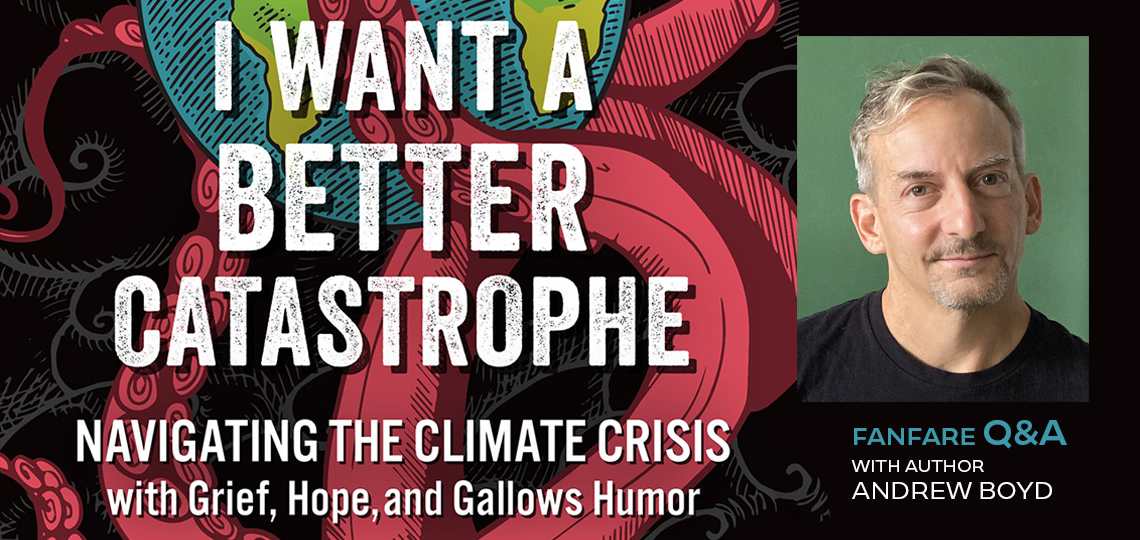

Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Andrew Boyd, Author of I Want a Better Catastrophe: Navigating the Climate Crisis with Grief, Hope, and Gallows Humor

From our perch in the wide and wonderful world of indie publishing, we’ve been blessed to connect with scores of fascinating authors, some of whom are working their tails off to change the planet for the better.

Which brings us to Andrew Boyd—he’s definitely one of the good guys in the fight against climate change, but he’s proved himself to be more thoughtful, more aware, more alive than the rest of us and his approach stands a chance, finally, of moving the issue to front and center of a distracted world.

In her review of Andrew’s I Want a Better Catastrophe, Rebecca Foster writes that Andrew’s I Want a Better Catastrophe “may well be the most realistic yet least depressing end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it guide out there.” She goes on to say that even while his “wisecracking and sardonic attitude temper the sometimes gloomy predictions he’s bound to report. He views gallows humor as ‘cosmic defiance, a reframing.’”

We asked Rebecca to put her all into the following conversation with Andrew and we are stunned with the result.

Can you briefly take us through your own journey from a hopeful activist to—whatever you might call yourself now; a realistic catastrophist?—as you look toward various future scenarios?

As I say towards the end of the book, looking back at the whole journey:

I’d begun this quest a hopeless-hopeful schizophrenic. And now—eight meetings, thousands of miles, and two flowcharts later—here I am at the end, still anguished by how much we’re likely to lose but still striving to lose as little of it as possible. In the end, I am an optimist and pessimist both.

It’s a cop-out to be a do-nothing pessimist, but given the brutal facts of our climate situation you can’t in good faith be a pure optimist. We need to hold the light and the dark of our situation, and I came to call the approaches I landed on as “can-do pessimism” and “tragic optimism.” And I came up with superhero-esque garments to get us in the groove:

Whatever tint is the opposite of rosy, that’s what color the goggles of can-do pessimism are. They let me see—in plain brutal terms how fucked we are. They also focus me on where I can help. When I put them on I become stubborn and purposeful; my eyes narrow in on the prize.

And when I’m brokenhearted, but still want to attempt large things, I reach for my cape of tragic optimism. I put it on and feel, well, broken-hearted—but now in a more soulful and empowered way. It will all end badly, I tell myself, but not quite as badly as it would if I did not act. So let me do something. While expecting nothing. While still longing for everything. And I call upon that grand longing—for everything wrong to be set right and everything broken to be set whole—to help me act in as large and openhearted a way as I can, even in the face of inevitable failure.

For the book, how did you go about choosing your gurus and ensuring a range of opinions and responses?

The “inciting event” that drove me to write the book was a crisis of hope. After thirty years of doggedly finding enough hope to take on cause after cause, I lost hope. In the face of the “impossible news” climate scientists are bringing us, I lost hope, or at least the kind of can-do, problem-solving hope I was used to. So, I set off in search of a darker, more robust kind of hope. Or at least an ethical way to be hopeless. I sought out leading climate thinkers—“remarkable hopers and doomers”—and sat down with them. So that was the first criteria: people who are not pretending things were better than they are. People who’d learned how to hold the awareness of our terrifying future, and all its complexity and contradictions in a grounded way, and still act.

And I wanted a diversity of perspective. Among them scientists, activists, psychologists, and wisdom teachers; folks from the east, west, and center of the country; only two of the eight are white dudes; some identify as Christian, others as Indigenous or Buddhist.

Climate activist Tim DeChristopher shared how action is his coping mechanism, likening it to how you get on a bicycle and start pedaling and that’s how you find your balance. “We’re going to suffer,” Gopal Dayaneni, a leading voice in the climate and environmental justice movement, told me, “so let’s distribute that suffering equitably.” “We’re in for a big fall,” organizational healer, adrienne maree brown told me, “so, let’s fall as if we were holding a child on our chest.”

Our situation is unprecedented. I don’t have the answers. These gurus, as you call them, don’t claim to either. But each has something to offer, each holds a piece of the puzzle.

How have you tried to strike a balance between striving and resignation? For example, Dr. Guy McPherson mentions in your interview with him the Buddhist concept of performing the right action and then detaching from its consequences.

There’s a Jewish wisdom-teaching that basically goes: “It is not your job to save the world, but it is your job to ‘try’ to save the world,” that helps me stay grounded. So long as I’m trying—and not a “college try.” No, you have to be really trying to save the world, even if it is impossible, and you know you will fail—then I’m at least somewhat okay with whatever happens.

It’s basically the difference between an optimism that ultimately depends on getting good results, to a more values-based hope, where you’re doing what’s right because it’s right, independent of ultimate results.

You call yourself “a half-Jew, functional atheist” and “probably more Buddhist than any other religion.” What made you open to including spirituality as part of the environmentalist’s toolkit?

Our broken relationship with the natural world is at the core of the crisis. This is not only a practical relationship—how we farm, etc.—but a spiritual one. Are the plants and animals we share the Earth with merely objects? And thus merely there for our extraction and consumption? Or are they our brother and sister species? Or, even our elders and teachers, as Indigenous botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer said when we met.

If the latter, they are sacred, our equals or more, and to honor them and live by that understanding, our entire civilization would have to radically change—in exactly the ways we need to change if we are to long-term survive the ecological crisis we have plunged ourselves into, and live in harmony with the natural world we depend on for our existence.

Second, the crisis is existential in nature. Not only is the survival of humanity literally on the line, but how we respond, both as individuals, and as a society, involves questions of hope, faith, solidarity, and responsibility that go to the core of who we are—a reckoning that could be aptly described as spiritual.

When we’re living in the mundane everyday—chores, deadlines, family commitments—it can be hard to bear the cosmic in mind and live as if there’s this inexorable disaster unfolding. (Of course, some are unaware of or in denial about it.) Do you find it’s something you can momentarily forget about? Do you have to deliberately remind yourself by, say, following science news?

Just the other day, I woke up to the sun streaming in my window on a gorgeous 55°F day in New York. I was overjoyed. And then as my brain woke up more fully, I remembered it was the middle of February and this shouldn’t be happening at all! Sure, I went out and enjoyed the sunlight. Who wouldn’t? But all through the day, I was on and off aware that this same personal loveliness was part of an unfolding disaster for our planet and our future.

In the book, I refer to this awareness of impending catastrophe as the arrival of “impossible news.”

It is painfully surreal trying to get on with daily life knowing there is a horrific catastrophe around the corner. And it is made all the worse by the fact that our leaders are not taking sufficient action, and we as a society are not treating it as the emergency it truly is. Jenny Offill brilliantly captures this haunting awareness in her 2020 novel Weather.

In the course of the conversations in the book, I’ve noticed people adopting various strategies: One person described herself “squinting at the apocalypse,” only letting in the sliver of bad news that she could handle. Another described how a few times a year, he has a full-on reckoning with how awful our situation truly is, and he’s “going, ‘Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!’ But then I’ve got to eat my nachos.”

When the impossible news hit fifteen-year-old Greta Thunberg, she went through a horrible period of despair and depression before she accepted the terrible truth of our climate situation and began to act. It was speaking her climate truth—and, crucially, acting on it—that allowed her to live with it.

In a similar vein, a campaigner friend of mine says, “Action is my coping—and hoping—mechanism.” I’d say I’m built that way, too. Yes, it’s awful, but at least I’m doing something about it (these days, primarily through my work with the Climate Clock). It doesn’t make the news any less impossible, but it helps me look it in the eye with a half-way clean conscience.

I think of something George Monbiot (whom you quote at a few points) once wrote, that the public has been conned into believing climate breakdown is a matter of “micro-consumerist bollocks” (e.g., ordinary people need to reduce their use of plastics), rather than holding corporations and governments to account for it. Is the language of personal, individual responsibility for environmental crises helpful, or shaming, or only part of the picture?

All of the above. It is not an either/or. It is a both/and. As I say in the book:

“We have met the enemy and he is us. No, them! But also us. But mostly them.”

The notion of “carbon footprint” was invented by the advertising firm Ogilvy & Mather in 2004 for their client oil major BP to avoid responsibility for the fossil fuel industry’s primary role in causing the crisis, and instead shunt it off onto individual consumers. They want us to feel guilt and shame, and too think we are to blame. But when we look beyond our recycling box, we quickly realize the entire business model of late capitalism is ecocide. And then we start demanding, as the kids say, “System change, not climate change!” Does this mean we shouldn’t recycle? No, we absolutely should. But we should do it—and every other ecological shift we can make as individuals—knowing that they are utterly insufficient to the task. As I say in the book:

Reduce-Reuse-Recycle is only a fraction of what we need to do, and recycling is only a fraction of that fraction, but with the future of the planet at stake, fractions of fractions count. So, let’s get cracking on the big system-wide changes we need, but let’s also recycle, let’s hold on to our appliances as long as we can, let’s fly less, let’s try to go vegan (or at least “consume no animal products before dinner,” as author Jonathan Safran Foer modestly suggests[1]). Let’s slim down our footprint wherever possible.

Doing so is not only good spiritual practice, it’s smart politics. Because when our opponents can’t trash our ideas, they try to trash our character—often, by cynically turning our own eco-morality against us. You want to be able to say to those people, “Yes, I recycle, thank you very much. Now let’s talk about eliminating that $467 billion dollars in fossil fuel subsidies.” (CNBC, October 29, 2021)

Your book is packed with ideas and stories and formats. When did you feel that you’d found a shape for it all, and know that it would come together?

Yes, the book went through at least five major reinventions over the nearly eight years I struggled to write it. It began as a series of vignettes, composite sketches of a-day-in-the-inner-life of folks with very different points of view on our climate predicament. These vignettes were based on interviews I was doing and take-aways from a series of “hopelessness workshops” I was convening. This early version of the book is mostly absent from the final book, but the best of them were published as “12 Characters in Search of an Apocalypse” in Dark Mountain: Issue 11, and have incited an ongoing conversation project that has now spread across three continents.

At one point, the entire book was structured around the 6 Stages of Climate Grief; at another point, it was a series of “Dilemmas at the End of the World;” at yet another, a more whimsical, What Would Jesus (and Camus/Marcus Aurelius/James Bond/etc Do about climate change? A key turning point came when a friend said, Enough with the composites; I like hearing the real stories of the actual people you’re interviewing. Which eventually led me to the final hybrid structure: a book held together by a narrative arc of me on a cross-country quest in search of a kind of hope worth having in our treacherous times, meeting with leading climate thinkers, and hanging my own gallows-humor-esque takes on grief, hope, and our possible futures off of the wisdom they’re laying down.

Dystopian fiction has been engaging with these issues for a long time, with “cli-fi” really coming into its own in recent years. I recall, for instance, from your chat with Tim DeChristopher, that he read The Road for a class at Harvard Divinity School. Do you think that fiction, and the arts in general, can push the conversation forward, and if so, in what ways?

Yes, The Road came up in my conversations quite often, a touchstone of a kind, a thought (and heart) experiment: is there anything recognizably human left in the bleakest of our possible futures? And, even amidst the wreckage and cannibalism of the novel, Tim was able to find a thread of resilience, gratitude, love, and maybe even hope.

While dystopian fiction can warn us of futures we want to avoid, helping us heed the warning signs here in the present and course-correct, too much dystopian fiction can numb us into assuming we’re locked in for the worst outcomes. This is where utopian (or “visionary”) fiction comes in, helping us to envision futures—and the pathways to them—that we never imagined were possible.

One of the other “remarkable hopers and doomers” I track down during the course of the book, organizational healer adrienne maree brown, thinks of visionary fiction as a “medicine of possibility,” and likens social change work to “science fictional behavior.”

Adrienne’s notion of visionary fiction (radical speculation to advance justice and liberation) is just one of the sci-fi/cli-fi sub-genres helping us imagine viable, non-terrible futures. There’s also hopepunk (being kind as an act of rebellion), retro-utopia (using cosmopolitan appropriate-tech to go forward by going backwards), and solarpunk (gritty, optimistic, post-carbon sci-fi).

“Artists are the antennae of the species,” said a wise person I haven’t yet been able to track down via Google. Along with climate scientists, tree frogs, sea coral, and those living on the frontlines of climate impacts, artists are part of humanity’s early warning system. It’s easy to think climate chaos is mostly a scientific, lifestyle, or policy problem. It might be far more a problem of simply being able to see and feel what is actually happening, try to imagine how it might happen differently, and then muster the craft and soul-force to tell those stories.

Who knows, in the end it might be the arts and the artists that save the world.

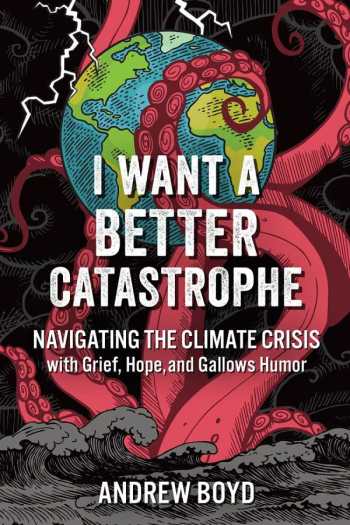

I WANT A BETTER CATASTROPHE

NAVIGATING THE CLIMATE CRISIS WITH GRIEF, HOPE, AND GALLOWS HUMOR

Andrew Boyd New Society Publishers (Feb 14, 2023)

“Mass extinction and social collapse” are “a hard set of lemons to be making lemonade out of,” environmental activist Andrew Boyd admits. I Want a Better Catastrophe is his inventive, no-nonsense manual of constructive and philosophical responses to climate breakdown.

Here, the climate emergency is a “personal existential crisis for each of us.” While Boyd—the founder of creative protest measures including the Climate Clock and Climate Ribbon—is used to hoping against the odds and the evidence, this text strikes a somber tone. Humanity, he writes, is on a “path of profound grief,” and to cope with this “impossible new reality,” people will need the wisdom, rituals, and stories that literature and spiritual teachers offer.

In keeping with the theories of the Post-Carbon Institute, the book envisions four possible routes for the human future, two of them disastrous (denial and competition) and the others more promising (“powerdown”—a drastic scaling down of economies and sharing of what remains; and solidarity). Eight interviews spotlight scientists, campaigners, and gurus who have reckoned with the worst-case scenarios. Their approaches vary: evolutionary biologist Guy McPherson predicts imminent human extinction; activist Tim DeChristopher, who attended Harvard Divinity School, advocates rituals and pastoral care; Buddhist teacher Meg Wheatley advises an embrace of chaos and pain; and Indigenous botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer speaks of gratitude to the earth and heart experiments, like asking oneself, “What do you love too much to lose? And what are you going to do about it?”

Boyd’s wisecracking and sardonic attitude temper the sometimes gloomy predictions he’s bound to report. He views gallows humor as “cosmic defiance, a reframing.” Along with dialogues, he slots zany figures, thought experiments, and honest anecdotes into his imaginative framework.

I Want a Better Catastrophe may well be the most realistic yet least depressing end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it guide out there.

Reviewed by Rebecca Foster January / February 2023

Rebecca Foster