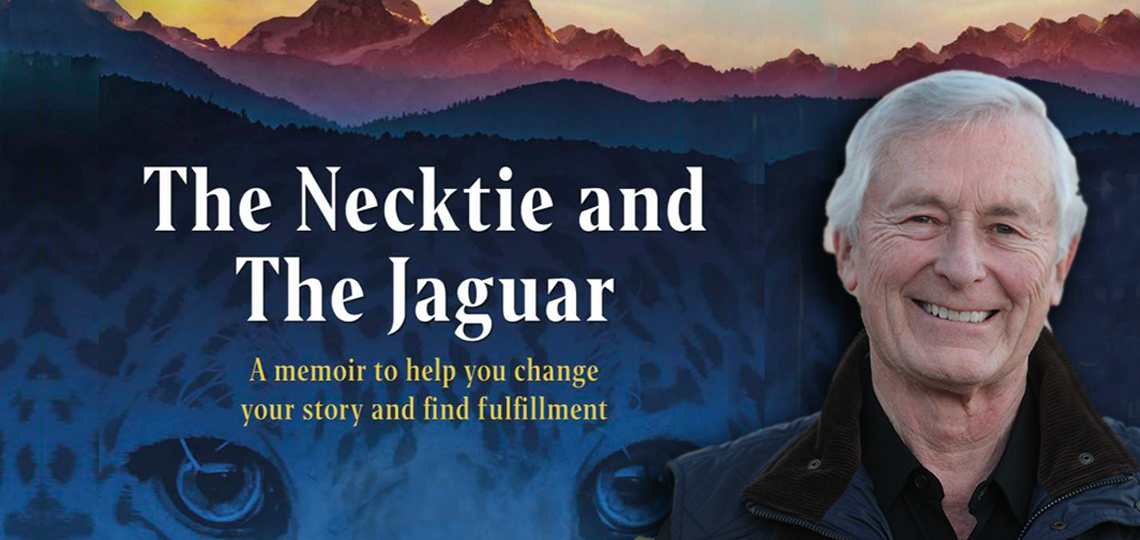

The Power of Self Discovery ~ An Interview with Carl Greer

The spiritual path contains a multitude of forks and branches along which to explore—it’s a very personal, intuitive, not-at-all predestined journey, and seekers come from all walks of life. In his own lifelong pursuit of personal growth, Carl Greer studied martial arts, Jungian psychoanalysis, and Indigenous shamanism, even while he captained a major Midwestern oil company through tumultuous times and raised a family. His is a very American story.

Upon the recent release of his memoir, The Necktie and the Jaguar, we asked Foreword’s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland to catch up with Carl for a heartfelt discussion about memory, legacy, serving others, and dying a good death—with lessons for all.

As a child, you had a great deal of freedom in addition to somewhat uninvolved parents: a mother who died from suicide when you were eight, and a stepmother who showed little warmth to you and your brother. Were your future relationships burdened by your boyhood experiences with your parents?

I believe that they were. You don’t know what you don’t know, but I don’t have memories of my home being a warm, nurturing place. Both consciously and unconsciously, I wondered if my future relationships would be warm and nurturing. For a while, I projected onto my relationships feelings that weren’t warranted. Sometimes, I anticipated warmth that wasn’t there, and sometimes I anticipated coldness and found warmth. It took me years to sort all that out.

The warrior in you was readily present through your teen years, as well as what you refer to as the “mythopoetic” you. Can you talk about those seemingly competing drives and their lasting impressions on your life? Do you believe it’s possible to overcome childhood baggage and unconscious wounds through introspection, analysis, or some other form of inner exploration?

In my teen years, my upbringing and cultural conditioning led me to identify more with the warrior—achieving, competing, being cut off from my feelings. I felt my mythopoetic self—the self that sought spiritual connection—would not serve me, so for years, I would mostly ignore its call for nourishment.

I do feel it’s possible to overcome childhood baggage and unconscious wounds, but it is a long process. For me, it involved Jungian analysis, working with my dreams, using shamanic processes—including shamanic journeys, rituals, and ceremonies—spending time in nature, and taking time to reflect on my life and make changes.

During your college years, you took to the road hitchhiking around the country, often sleeping on the ground to save some money, while taking temporary jobs at places like moving companies or dude ranches. Adventurous, to say the least. What drew you to the road?

My conservative Midwestern upbringing had not given me opportunities to satisfy my thirst for adventure and exploration, and I was curious about the larger world. While hitchhiking, I was picked up by, among others, a Catholic priest, a Protestant minister, a college professor, inebriated gamblers, a group of Hell’s Angels, and even a guy who had been convicted of and served time for murder. Those experiences made me recognize that there was much I didn’t know about different ways of living!

After earning advanced degrees at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Business and teaching there, but without much business experience, you were hired into a top management position at Martin Oil Service, an independent gas station operator with stations in thirteen states. Competing against Shell, Exxon, and other mega corporations, you also had to weather big changes in the oil industry, including the OPEC oil embargo cutting off oil to the US from the Middle East, and union battles with the Teamsters. Throughout the book, you give partial credit for your success in business to your martial arts training. How did that training influence you in some of your business dealings?

Two martial arts principles that influenced me were kime and ma. Kime is the idea of the right focus at the right time: You remain loose until the moment that requires concentrated, focused action, which is followed by being loose again. The idea is to not waste energy being tight and to know the right time to make your move. In one business negotiation, I had done a lot of research and analysis, but then I had to both say yes to a deal and make it happen within a very limited timeframe. The period of concluding the deal was intense, and I planned to relax afterward, but I stayed focused (“tight”) up until the very last minute. I even followed through on a detail that could have been missed and cost the company millions.

Ma is the idea of maintaining the right distance from people and situations. If I was too close to a situation, I could lose objectivity. If I was too detached, I wasn’t as involved as I should have been. Practicing ma helped me interpersonally when people I was dealing with became very emotional and even aggressive. It helped me to not be overly influenced by their emotions and respond in kind but rather to stay cool-headed, listen, and respond effectively. In other situations, it kept me from being too detached and unsympathetic to what was very important emotionally to the person I was dealing with.

In regards to your career, you write that you “tried to burn out the more mythopoetic parts of myself through hard work and self-discipline.” What was the personal cost of devoting many years to business?

My business endeavors allowed me to fulfill my desire to achieve success as I had learned to define it. I also accumulated resources that enabled me to support my family and later, to give back to philanthropic causes. In addition, I developed competencies that have served me well. In retrospect, being involved in business was a necessary step in my evolution to where I am now. But my business career wasn’t sufficient to feed my longing for meaning, purpose, and spiritual connection.

You credit your ability to compartmentalize as both a strength and a weakness. How so?

It was a strength in that by keeping a number of different aspects of my life contained, I was able to be involved with my family and in business, martial arts, other sports (such as platform tennis), and education (I was studying to be a psychologist). The downside was that because each of these worlds took a lot of energy, I wasn’t always able to be completely present in them. For example, I gave my family relationships less attention than I could have. If I had been more conscious of the downside, maybe I would have paced myself or reallocated my focus, maintaining different priorities.

In midlife, you hit a rough patch with your marriage and children. You write, “I was beginning a long journey toward evolving into someone who is more emotionally connected to people and less focused on competition and achieving success as it has been defined traditionally. I’ve had to learn to be honest with myself about my shortcomings and my choices. Altering old patterns and beliefs takes a lot of soul searching and a lot of feedback from people who make you uneasy because they call you out for what you say and do.” Obviously, this is a critical moment—perhaps the first time you were confronted by the people you love, and no doubt the experience left you feeling extremely vulnerable and conflicted. How did you turn this pain into a positive? Did your father also deal with similar circumstances based on his own life choices?

The pain caused me to embark on self-exploration as to where I had been, where I was going, and how I was living. I did this through Jungian analysis, pursuing training as a clinical psychologist, and eventually, studying shamanism. These activities, which weren’t common among men with my upbringing, helped me to better understand myself and make positive changes in my life.

I think my father was confronted by similar circumstances, but either by choice or by lack of opportunity, did not deal with them the same way I did. He drank to manage his pain, had difficulty being vulnerable and expressing his emotions, and was given to angry outbursts. All of that is the case with so many men. I can’t know what was going on inside my father’s head, but I believe he died with some unresolved inner conflicts and anguish even though toward the end of his life, some of his hard edges were beginning to soften.

Did losing your mother early affect your relationships with women?

I believe that it did. On the one hand, I learned to survive without much of a maternal, feminine presence, so I could be somewhat more independent of the feminine than others are. At another level, it made me more vulnerable because I was yearning for and needing the connection I would have had if my mother had lived. I believe I would have been more emotionally available in my relationships had I not suffered the loss of my mother.

Your work in Jungian therapy immersed you in the study of the masculine archetypes: warrior, king, magician, and lover. We might guess you identify with the warrior role, but what about the other archetypes? Why do you find Jung’s work to be so effective in shedding light on our life’s journey, hero or otherwise?

As an analyst, I have talked to my analysands about the danger of identifying with any particular archetype. We can note that we’re under the influence of a particular archetype without starting to believe “I am the magician” or “I am the warrior.” By not over-identifying with an archetype, we have more freedom to recognize where it is helping us and where it is hindering us and work toward resolving the imbalance. We can also see where we’re being influenced by other archetypes. In my own case, I have attempted to dance with both the positive and negative aspects of the warrior, king, magician, and lover. It’s a continuing process for me.

Jung’s work, as well as my shamanic work, has been effective in giving me insights into my life journey I might not have had otherwise. That’s because they have allowed me to explore unconscious determinants of my behavior in both my personal unconscious and transpersonal realms, including Jung’s collective unconscious.

Like other Jungians, do you also value insight gleaned from dreams?

I do, and I have had many dreams over the years that I have worked with that have helped me gain insights and energies for changing how I am in the world.

At the close of each chapter in The Necktie and the Jaguar, you offer readers an opportunity to reflect, perhaps even journal, on how your life experiences might also spur memories and insight into their own lives. With some of those engaged readers in mind, can you talk about the reasons you decided to write the book? And please also give us a sense of why you chose the title The Necktie and the Jaguar?

I decided to write the book in part to reflect on my own life. Years ago, I was a reader of Carlos Castaneda’s books and believed in the power of life reviews that he suggested. Beyond that, I was motivated by wanting to leave something for my family and friends to remember me by. I had written two self-help books (Change Your Story, Change Your Life and Change the Story of Your Health) in which I incorporated questions for the reader. As my memoir was taking shape, I realized there was an opportunity to suggest questions about the themes I was grappling with in various stages of my life that readers might want to ponder in relation to their own lives.

I picked the title The Necktie and the Jaguar to represent the juxtaposition between the conventional world in which I grew up—a necktie being somewhat constricting—and the mystery of the jaguar, which in Andean mythology can travel between the worlds of life and death, between the realms of the conscious and unconscious.

You’ve spent part of the last twenty years deeply involved in working with indigenous shamans around the world. About this experience, you write, “my main desire in entering a shamanic training program was to satisfy my longing for a richer experience of my life and a closer relationship to God, or Spirit. I wanted to not just believe that we are all interconnected, or accept that idea intellectually, but actually experience it.” Additionally, you say that through shamanism, you hoped to “learn how to die a good death: with equanimity, satisfaction with how I had lived, and as much consciousness as I could bring to the moment.” Can you talk specifically about personally experiencing the realization that we are “part of a great mind or consciousness shared by all,” as you say?

As a young boy, I wandered into a farmer’s field one day and saw ahead of me a lone apple tree that suddenly seemed to be glowing. I had the distinct feeling that I and the apple tree and all that surrounded us—the sky, the earth, the farmer’s crops, the wind, the birds—were all one, with no separation between any of it. It was an extraordinary feeling. Many years later as an adult, I underwent a shamanic journey in which I unexpectedly encountered a realm that I knew to be the place before creation, a place I call the Quiet. It’s a place of pure potential that exists before the introduction of an idea or its form or energization. I’ve come to believe that this energetic realm coexists with us in every moment, and it’s from this realm that shamans work to cause things to happen in this lifetime that perhaps otherwise wouldn’t. And on other shamanic journeys, I’ve encountered the Matrix of infinite connections linking all that is, has been, and will be—past, present, and future—through energetic cords.

As for dying a good death, it is something I strive for as a result of my experiences in transpersonal realms and what I encountered there. I believe that I came from the Quiet and I will return to it at my death.

Your later work in shamanism includes workshops to help attendees access their own unconscious, occasionally including medical professionals seeking guidance on integrative medicine. Do you sense a shift is happening in the medical community, an opening to other forms of healing and not such a heavy reliance on pharmaceuticals and Western ideas?

I don’t know how many medical professionals are interested in holistic, integrative approaches compared to in the past, but I do know there are those who believe that illness has spiritual, psychological, energetic, as well as physical components. They recognize that effective treatments for illness could include interventions such as eating more healthfully, taking nutritional supplements and herbs, getting massage and undergoing chiropractic treatment, or working with essential oils, color therapy, and acupuncture.

In the shamanic and Jungian realms, interacting with inner figures that are related to healing frameworks, such as one’s inner healer, which can serve as a personification of one’s immune system, can be effective for healing. Dialoguing with our symptoms, asking questions and listening to the answers they give, can be a powerful technique for healing, too.

You and your wife are currently working with over sixty charitable organizations. Do you find this service to others to be a natural extension of your years of study in analysis, shamanism, and various other disciplines involved with accessing the unconscious?

According to the Tao Te Jing, there’s a stage at the end of life called the Way of the Return: You ready yourself for your reunion with Source by releasing into the world the knowledge and wealth you have built up over a lifetime, giving back in service to others. I’m in that stage now: All of the work I’ve done has helped me at this point in my life to realign my priorities as to how I want to spend my time and my resources. Analysis, shamanism, and other disciplines have helped me change my objectives and priorities. These days, I feel it’s more important than ever for me to share what I have with others and make a difference in people’s lives at the physical level but also the spiritual and psychological levels. I do that through my charitable work. I also do it through teaching and writing (and the proceeds for my books all go to charity).

At any point, we can wake up to the benefits of being less self-focused and more tuned in to how we can serve others and the earth. Maybe my writing and charitable work will inspire some people to do that.

Matt Sutherland