The Sioux Chef Talks Native American Cooking

Let’s play a word association game. What’s the first thing you think of when you read: indigenous North American food and cooking?

Fry bread, tacos, wild rice … If you’re drawing a blank, don’t beat yourself up. You need to remember that when the US government went to war with the native American tribes back in the 1800s, one of the goals was to eradicate indigenous culture. Consequently, we have very little knowledge of how the hundreds of tribes fed themselves, and much of what little we know is buried in the memories of aging tribal elders.

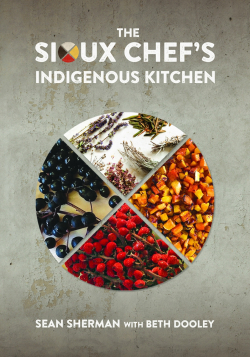

All of which makes Sean Sherman’s The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen hugely important and exciting. We asked Foreword reviewer Eric Patterson—an award-winning chef himself—to catch up with Sherman for a chat about the urgency of capturing indigenous food memories, whether Native American cooking is primed to be one of the next big cooking trends, and anything else he wanted to know about Sherman’s work. Based on the repartee, they both seemed to enjoy the experience. Here’s Patterson’s review of the book.

First of all, congratulations on your book; it’s great.

Thanks, man, I appreciate that.

How’d your tour go?

It went good. It was pretty crazy, but we got through it. Ready to be home after that month on the road.

I’m sure. Is the book being received well?

It’s blazing through its second pressing; it’s almost on its third. This is our first book, so it’s all new to us, but rocking it.

As I was reading it I thought this is one book, but could be many. Do you see in the future a work incorporating more indigenous or traditional techniques? Right now there’s a lot of what I would think of as French techniques.

Yeah, for sure. We really wanted to keep the first book simple, to help readers understand and comprehend, and kind of open their eyes to what’s around them, no matter where they’re at, when it comes to indigenous cultures. We definitely want to work on more. I would love to do a book showcasing the diversity of North America—there’s just so much indigenous culture out there.

Is there much difference in the way that indigenous cooking is done throughout the country, or are techniques pretty similar?

We look at the immense diversity that’s out there—there are 567 tribes in the US, 634 in Canada. And in Mexico, one-fifth of the country still speaks indigenous languages. There’s so much indigenous food culture still alive in Mexico. Areas where agriculture developed, some where it didn’t. People using permaculture and wild foods for everything. There’s a lot of differences.

But with cooking techniques, you start to find a lot of commonalities, because it’s really basic. You’re cooking with simple elements: fire and water, dehydrating foods and rehydrating foods. It helps to look at all of North America instead of just focusing on one tribe. There’s so much out there, and every tribe and region is unique.

I was struck by the “no fry bread” principle in the book and the idea that the people who control the food control the power. I kind of see that as your mantra throughout the book—basically taking the power back for indigenous cultures. Could you talk a little bit about where this whole concept comes from?

Driving the work is trying to right a wrong. I do a lot of talking about how colonialism works and how it affected indigenous communities. I showcase how fast it went down. At the turn of the 1800s, over 80 percent of the country was still under indigenous control. By 1900, only 1 percent was left under indigenous control. It really got wiped out fast in the latter part of that century. The reason we don’t see a lot of tribal and indigenous food businesses is just that everybody went through an immense amount of trauma. Post-colonial Native America has been nothing but a lot of hardship, even up to today. We look at boarding schools at the turn of the century that tried to wipe away culture completely. The US and Canada really did a really thorough job of trying to destroy those cultures.

For me, growing up on reservations in the 1970s and 1980s, there was very little left—especially the food. What people are working off of today for food, commodity food lists, it’s just a bunch of processed foods. But that’s what people have been surviving on for the past few generations, and the problem with that program is that it’s not nutritional, it’s just a farm supplement program. It’s done immense damage to the people. Native Americans have two to four times more chance of type 2 diabetes. Some communities have 60 percent of their people with diabetes, and very little food access, because they’re still living off of government reliance.

We’re trying to find ways of reclaiming a lot of the knowledge and practice through food, and it’s just giving people something back. If we can figure out the Rubik Cube problem of breaking that system and pushing for food sovereignty in the truest sense, we’ll start to see a lot of change.

How did you research true indigenous cuisine?

It was actually pretty difficult. I had my epiphany moment and wanted to figure it out, but there just wasn’t that much information out there. I really had to dig deep, search through ethnobotanical, archaeological, historical records; talking to elders. The key for me was practicing it more and more on a daily basis, sifting through it with a culinary lens and perspective to understand food before colonialism.

We’re not trying to do a time piece; we’re trying to absorb as much knowledge of the past as possible, but utilize a lot of the knowledge we have today.

How long have you been actively pursuing this?

The first time I tried to do an all indigenous menu was in 2004, then I took some other jobs. But from 2008 onward, I’ve been focused on trying to understand. I spent 2008 to 2012 just filling up my head with whatever I could find on the subject, which I’m still continuing, but as of 2012, I’ve started actively practicing and trying out some dinners. By 2014, I had started my own business and by the end of the year, working for myself.

What was the reception like?

It was received well. I tried this out with indigenous crowds, so the first couple dinners were in Minnesota and it was was very well received. It seemed an obvious path to continue to pursue.

With the taco trucks, utilizing only regional indigenous ingredients, we were going against the grain of even what Native Americans were considering Native American food. With fry bread, we just thought that there was so much better education to think about and move forward with—agriculture, wild foods, game, simple cooking techniques.

This definitely does cross over with more of that European feel in some of the recipes, with Beth’s help. She did an awesome job. It was a huge project for her. She was learning so much so fast, there was a lot to take in, she was really scared of how it would be perceived by people, or that they wouldn’t understand it.

It would be fascinating to see some of the indigenous cooking techniques, just from a chef’s point of view.

We’re really hoping to try some of that, with research and development through the nonprofit and the Indigenous Food Lab, creating more educational resources. We’re hoping that we can really delve into educational resources for people, if they’re interested in learning more about indigenous food.

Are there any world traditions that have informed your techniques?

Talking to elders, and getting a lot of memories—when we started doing these dinners in tribal communities—these elders hadn’t had some of these flavors since they were young, but this food triggers hidden memories that they hadn’t thought of for a long time. Then we get a flood stories, of food from their grandparents, of walking through the woods or going out into the lake and collecting plants and things like that. It started to become more and more about that.

It sounds like another generation from now, this might not have even been possible.

I think that the timing was key—it had to happen now. When I was educating myself, everything was telling me that I had a little time to study, and I had to do it, I had to get it out there. I wish my parents’ generation could have recorded a lot more information, when there were more elders to talk to. Basically, it’s the generation of my great grandparents that we’re studying.

All of my grandparents grew up Lakota and were born at the turn of the century. They’ve passed now, but I would have had a lot of questions for them. Luckily, there are a lot of elders around the country, and there have been some good works. I think of Nancy Turner, who’s a professor in Victoria, who’s recorded an immense amount of ethnobotanical work in the Pacific Northwest, British Columbia, over a hundred year stretch. It’s been awesome to have some of those resources that people worked hard on.

There is a movement happening. We feel it, we’re in it constantly, traveling the country and working with different groups. It’s up and coming. There are a lot of players; we tried to convey that by having other voices in the project, too. It’s not just about us. We wanted to go into the culinary project and remove the ego completely, which is rare in the culinary world.

People like Loretta Barrett Oden, or Lois Ellen Frank, who did Native American Cooking 1991—she’s done an immense amount of work with Gary Nabhan. She’s awesome, and she’s been doing a lot of work for a long time. We tried to challenge ourselves to do something different by using only indigenous ingredients. That set us apart. We’re seeing a lot more people falling in line with that perspective, trying to decolonize the food and make something that feels authentic, maintains health, and speaks to the region.

What’s the biggest challenge you face right now? Finding ingredients? The health department? Do they give you any crap over this?

We’re lucky in Minneapolis; we have a good food scene, a lot of coops, good foragers, and the way that we’ve done it is by prioritizing indigenous vendors. We’ve been leaning on native farms. They have the licenses to sell, and we’re using a lot of their outlying plants. They’re actually pretty happy for us to come out and basically weed the gardens. There’s just a bunch of flavors that we can use. One way that we’ve been going about that is by staying within the rule sets, but being creative with them.

What are your short term and long term goals?

We kind of accidentally created a lifetime of work, more work than I’ll be around to do. But we’ve created the nonprofit, and we’re trying to open up a building in Minneapolis that will be the heart of the nonprofit. The two goals are indigenous education and food access.

The model that we want to utilize for the future is a live restaurant as a training center. We feel that live training is effective, and then the indigenous food lab, which will be a place for people to come and learn about the various parts of the food: native agriculture, cooking techniques, food preservation. We hope to develop this as a business model that other tribal regions can use. We hope to impact what the next generation thinks of as traditional foods, and help them move towards better health. We want it to be replicable across the nation.

There’s a shortage of young chefs, generally. Are you seeing interest in the younger generation for getting into cooking?

We’re seeing a lot of interest. Fifth to ninth graders are really interested. I think it’s going to be okay. At the James Beard dinner we did recently, we had an eleven year old girl on our team. She was a Mohawk from that region, with experience.

We’re creating community places that embrace young people. We’re going to have apprenticeship programs that make it easy for kids on reservations to apply to work with us right out of high school.

You seem to have arranged the book based on where ingredients are grown.

We split it up a few ways in the beginning. It was never going to be just soup, salad … that arrangement. It was always more about looking at the big picture: wild food, agriculture, cooking techniques, hunting, fishing, things like that. We wanted to compartmentalize it in that way. The recipes kind of become a choose your own adventure. You can go backwards in the book, or look at them from a different perspective.

What are your thoughts on cultural appropriation, or white chefs trying to utilize these techniques?

That’s a good question and something we’ve been talking about a lot recently. The biggest thing, I think, is that it benefits everyone to be curious about history, the land, where you’re at. Learn from indigenous cultures, and their thousand years of experience versus fifty years of Eurocentric colonial ideology.

When it comes to cultural appropriation, there’s a fine line. If you’re a white chef and you open up a Native American restaurant, you’re going to face a lot of hard conversations. But if you’re just celebrating the knowledge, foods, and flavors, you don’t have to call yourself a Native American restaurant to do that.

Someone who does it well is Pascal Baudar. He’s out on the West Coast. He’s a wild food expert who has a beautiful cookbook using only wild foods of the California region, and his techniques cross over into Native American cooking techniques and lessons, but he’s never called himself a Native American chef. It’s fine if you’re just understanding and appreciating regional food.

It’s a touchy subject. There will be people who want to capitalize on other cultures; they’re going to have hard conversations.

Eric Patterson