The Vulgar, Intelligence-Insulting, Mudslinging Campaign ... of 1840

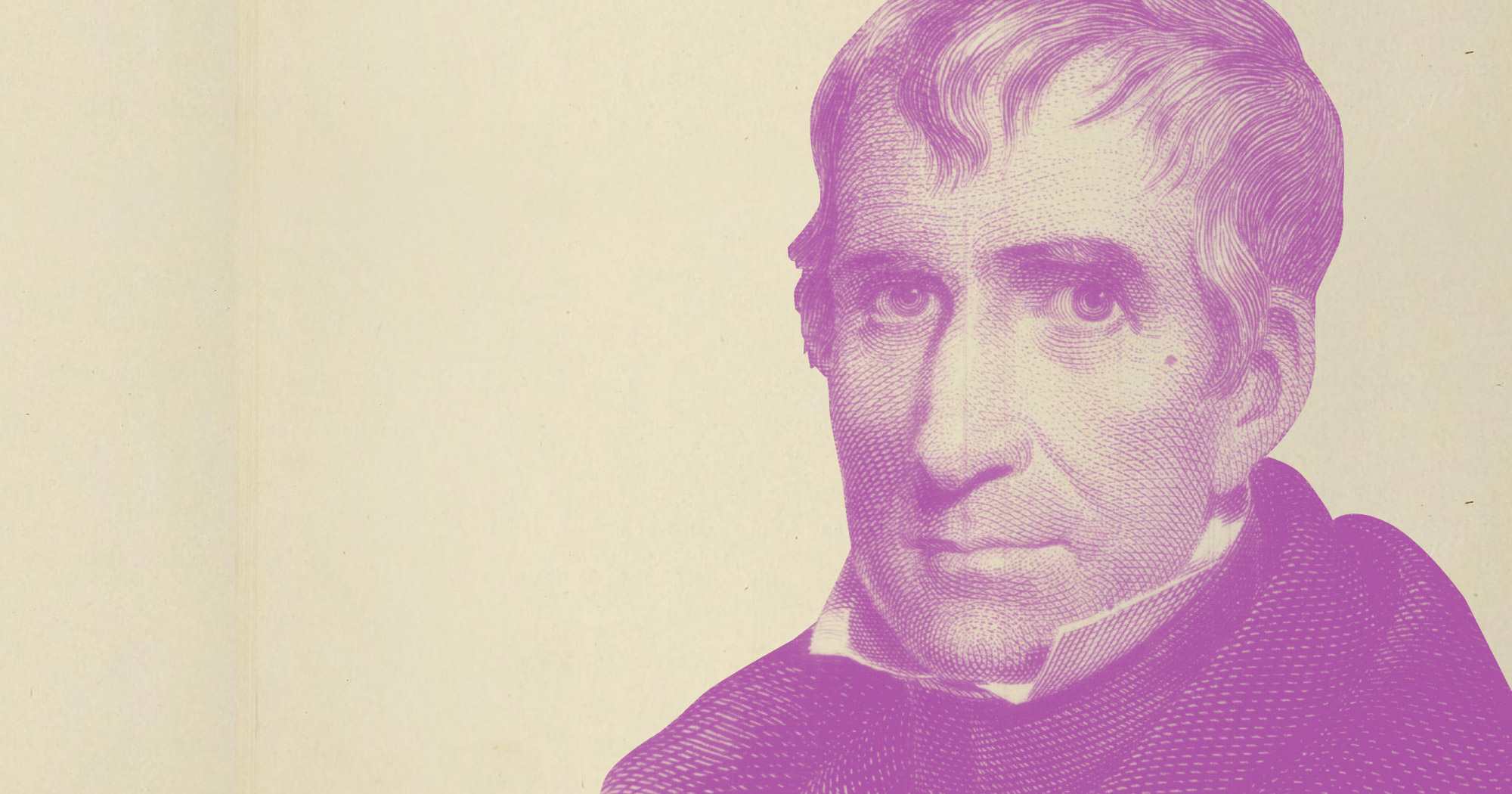

Allegations of candidate infidelity, a circus atmosphere, and fact-free image over reality. Yes, you’ve guessed correctly. I’m talking about the presidential campaign of 1840 that pit Martin Van Buren against William Henry Harrison. What? Did you think I was talking about any other presidential campaign?

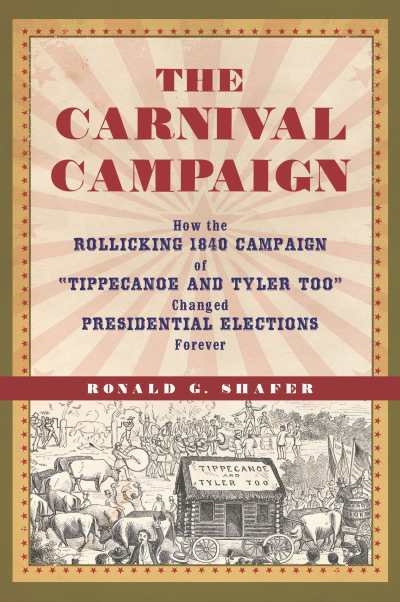

While Election 2016 is certainly a circus, with all the usual clownishness taken to new heights, it is built upon tents pitched back in 1840, when presidential contenders decided to get their hands dirty for the first time and sling mud at one another. Ronald G. Shafer, former Wall Street Journal reporter, has covered his share of modern political campaigns, but for his new book, he decided to go all the way back to the beginning. The result is The Carnival Campaign: How the Rollicking 1840 Campaign of “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” Changed Presidential Elections Forever (Chicago Review Press).

Below, I ask Shafer about the roots of the kind of intelligence-insulting campaigns that we’ve seen since 1840. And, of course, I ask him which candidate he supports … Van Buren or Harrison?

Name a few ways the seeds to Campaign 2016 were sown in Campaign 1840.

Ronald G. Shafer: 'Personal insults led to the invention of modern campaign tactics'

The 1840 campaign began the traditions of big presidential campaign rallies, speeches by the candidates themselves and the involvement of women. Ladies couldn’t vote in 1840, but Whig women swayed their husbands and boyfriends. Women finally won the vote in 1920, and in 2016 a woman is running for president.

Before the 1840 election, presidential candidates considered it beneath their station to actively campaign. Then, what you call the “carnival” began. What changed?

Personal insults led to the invention of modern campaign tactics. Critics jeered that 67-year-old General Harrison would rather sit in his log cabin and drink hard cider. So the Whigs wooed average voters by portraying Old Tippecanoe as the champion of the common man in entertaining grass-roots log cabin and hard cider rallies and parades—even though Harrison really lived in a mansion in Ohio. After opponents derided Harrison as “General Mum” for ducking issues in responses to voter letters, he decided to become the first candidate to campaign. This was so shocking that he drew crowds as large as 100,000 people.

There was no Fox News, no CNN, no Twitter in 1840. Still, did that campaign see the beginning of candidates slamming the press even as they depend on it?

Newspapers were fiercely partisan, freely spreading lies about the opposition candidate. Like modern candidates, Harrison complained that the media took his comments out of context. “It seems almost incredible,” he said, but from a long speech “short sentences have been taken” and twisted from their original meaning.

There has always been racism, sexism, and ant-immigrant rhetoric in campaigns. Maybe even references to private body parts. But is 2016 really the most vulgar in history? How does 1840 compare?

The current campaign takes the trophy for vulgarity, but the 1840 one got plenty down and dirty. Harrison used “SHOCKING PROFANITY,” critics charged. Democrats dredged up a decades-old allegation that Old Tip had seduced a young woman “in an act of such a deep and damning nature that virtue must ever blush in crimson.” Whigs charged that Harrison’s opponent—President Martin Van Buren—had turned the White House into a “palace of splendor,” surrounded by grassy mounds shaped like “AN AMAZON’S BOSOM” with a knoll at the top “to depict the nipple.”

Let’s say you’re a voter in 1840. Are you for Van Buren or Harrison?

Who to vote for in 1840, Harrison or Van Buren? If you’re the average man, you probably went for Old Tippecanoe because in the middle of an economic depression Van Buren refused to offer any government help while the Whigs promised “Harrison and Reform.”

As a historian, can you assure us that, no matter what the result, November 8 will not be the last day of the American experiment?

I am a journalist more than a historian, and based on covering so-called political revolutions over 30 years, I predict that Nov. 8 won’t be the last day of the American experiment. Even in the gloom of the 1840 election loss, an anti-Harrison newspaper said, “People will ultimately recover from the delusion into which they have fallen.” Sure enough, the Republic survived, though poor President Harrison expired after only 31 days on the job. Bummer.

Howard Lovy is executive editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow him on Twitter @Howard_Lovy

Howard Lovy