This Place: 150 Years Retold

Reviewer Peter Dabbene Interviews Indigenous Authors of This Place: 150 Years Retold

Canada, our cheerful, polite neighbor to the north, hasn’t always lived up to its ideals. Just as the US grotesquely mistreated its Indigenous population over the course of centuries, Canada, too, implemented any number of federal, provincial, and local policies to keep its native peoples from reaching their potential.

One of the most egregious forms of disenfranchisement is the act of silencing the voices and stories of a population. Not only does it keep the dominant majority from understanding (and valuing) the lives of fellow countrymen and -women, it also serves to keep the minority population from knowing who they are, how they came to be, and other important aspects of their identity. Throughout Canada’s history, Indigenous people were isolated socially and culturally, their voices and experiences all but erased from the public record.

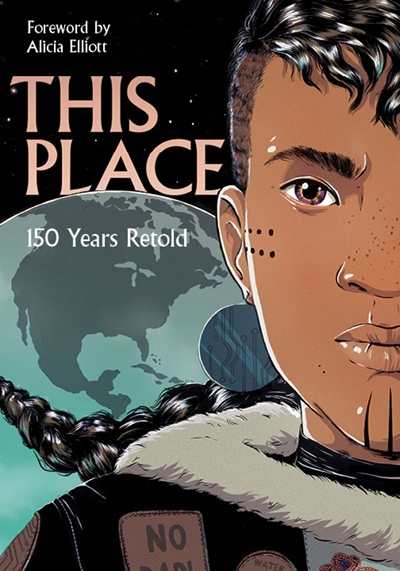

This week, we’re extremely pleased to hear from a handful of the writers behind This Place: 150 Years Retold, a graphic novel of immense importance to Canada’s historical record. As is the routine with these Foreword This Week Face Offs, we assigned reviewer Peter Dabbene to interview four of the twenty-one Indigenous Canadian writers and illustrators who contributed to the book, beautifully published by Highwater Press. Peter gave This Place a starred review in the May/June issue of Foreword Reviews.

Here’s a snippet from the review: “The talented writers and artists of This Place tell stories of protest and uprising against Canada’s government, including incidents seldom discussed outside of Indigenous communities. … But first and foremost, [the book is] a collection of exciting, entertaining, beautifully drawn stories; as Alicia Elliott states in her foreword, ‘Every Indigenous person’s story is, in a way, a tale of overcoming apocalypse.’”

Peter, take it from here.

Typically, with a compilation of short pieces, there’s a single editor—maybe two—who guides the process and puts it all together. Although there’s a foreword by Alicia Elliott, This Place: 150 Years Retold is unusual in that it doesn’t have an editor credit. How did this project come about, who organized it, and how did you get involved?

Katerena Vermette: The legend has it that David Robertson, Catherine Gerbasi (our publisher), and I were just chatting at an event a few years ago and came up with the idea, spontaneous-like, in conversation. Don’t know who first thought of it, but it was a “wouldn’t this be great!” “And we should do this!” “And this!!” kind of conversation—we were on fire!—that Catherine really loved. She went back and wrote the proposal in two days (I think she had some help from the Portage and Main family, too) and sent it along to the Canada Council’s 150 grants. The rest, as they say, is history.

David A. Robertson: I know that there was discussion around a project that would take the Canada 150 stuff, and flip it on its head to open up a dialogue about 150 years in Canada from an Indigenous perspective. The concept, to me, was to shed light on the reality that this place that we now call Canada has more history than we are aware, and that history has been ignored, or told by others. It is a project of reclamation and reconciliation.

Jen Storm: I was approached by Cathy [Gerbasi] to participate while she was in the process of applying for a grant to fund this project. When she told me the idea of having Indigenous writers rewrite Canadian history from our perspective, I immediately jumped on board. The project was huge and it was handled with so much care and passion. Laura McKay worked with all the writers and artists and I believe her work in this is what really polished it off.

David, your story “Peggy,” about Francis “Peggy” Pegahmagabow, was fascinating, artfully compressing a very full life into a limited number of pages. Was it difficult to decide what to include, and what had to be left out?

DR: Yeah, I mean, part of the challenge in writing about somebody’s life, or writing a story at all, in the constricted space that you have, such as with “Peggy,” is that you have to decide what goes in, and what does not. What you’re looking for, in all the moments of his life that we know about, is a common thread that can create a narrative. You sew those moments into the thread, and hopefully end up with a story that is compelling, engaging, and thought-provoking. There is so much more to Peggy’s life than what is in these pages. I would encourage anybody to continue to learn about him, and of the many stories held within these pages, and the stories that are not, that exist in the incredible Indigenous literature being written today, by Indigenous writers.

Jen, your contribution to the book “Red Clouds” tells a fictionalized story, but is faithful to the larger truths of the story of Jack Fiddler, the first Indigenous man to be charged as a serial killer. Can you talk about how using fiction in this story provides other insights beyond what’s been strictly documented in history books?

JS: The fictional parts are the women’s (and windigo’s) quotes, and I switched Wasakapeequay’s “windigo-ism” (I just made that up), from her original mental psychosis to that of cannibalism. The cannibalism portion of the story is also true, and in its original form, the woman was cured and lived to be a very old woman. So I merged the story of two windigo’s from Fiddler’s past into one. There isn’t much, if at all, in the history books that discuss what the women were saying or experiencing with regards to these situations. Most certainly nothing from the Windigo spirit survivors. I really wanted this story to be told from Wasakapeequay’s perspective (the female windigo) because there is already a great book written on this story from the Fiddler family’s perspective (Killing the Shaman).

Katherena, I’d guess that most of the historical figures featured in your story, “Annie of Red River”—and the entire book, for that matter—would be unfamiliar to most US citizens. In the introduction to your story, you mention that Annie Bannatyne’s whipping of Charles Mair, who had besmirched the honor of Indigenous women, inspired Louis Riel’s own efforts to preserve Métis rights and culture. Having never heard of Anne Bannatyne or Louis Riel previously, I’m curious: are they well-known figures in Canadian history?

KV: I hadn’t heard of Annie Bannatyne until a few years ago. So, like most figures in the book, she is quite unknown. But isn’t she memorable!? Louis Riel, on the other hand, is very well known and quite iconic to the Metis (and some others too, like Manitobans and Quebecois). But, like many historic Indigenous leaders, the Canadian version of the story lingers with many untruths and he’s still rather controversial to the rest of Canada.

Richard, the stories in this book are satisfying in their own right, but they’ll also inspire curious readers to look further. Your story, “Like a Razor Slash,” highlights the speech given by Chief Frank T’Seleie in 1975 against a proposed pipeline, and also points readers to video of the speech online, which makes a nice endnote to the graphic novel experience. You spoke to Mr. T’Seleie while writing the piece—what did he think about you creating a comic book version of his life?

Richard Van Camp: Frank T’Seleie, I felt, was deeply honored that a comic exists now that celebrates his timeless speech that he wrote in a few days when he was 28 and delivered 43 years ago this August 5th, 2019. I was 4 years old, in Fort Smith, when he spoke the words that won my heart.

I called him in Fort Good Hope on the 42nd anniversary of his speech at the Berger Inquiry and thanked him for protecting the land and for his leadership. He helped guide my writing with numerous phone calls and several emails.

Have there been any recent developments, positive or negative, regarding the Indigenous population or policies that affect them?

DR: This is such a broad question I’m not sure I would even know how to answer it. Of course, this is a vital time in Canada’s history. It is a time of reconciliation, but often I don’t think we really know what that means, or the scope of it. I am certain that the government isn’t all that sure what it means, based on the decisions that have been made at the provincial and federal levels, and the policies it has developed or disregarded. What I would say, I suppose, is that reconciliation in the end, should never be a policy. It will never work as a government directed movement. It is a movement of the people. This book will hopefully help to mobilize, and to create lasting change through knowledge.

This Place: 150 Years Retold is a tremendous achievement. Are any of you continuing to work on Indigenous stories? Any upcoming projects you’d like to mention?

DR: My whole writing career is focused on Indigenous stories of culture, community, history, contemporary issues. I am working on children’s literature, young adult novels, graphic novels, memoir, and middle grade novels. They all concern Indigenous peoples, and they all carry with them the intent of education through truth that can only come from lived experiences, or own voices. My The Reckoner trilogy is ending in May with the third book, Ghosts, but the rest of my books are kind of secret right now, and yet to be announced.

JS: I plan to continue to contribute Indigenous stories and characters for as long as I can! I’m working on a couple of new projects, but nothing is off to the printers just yet.

Peter Dabbene