Top Ten Fascinating Responses from a Fabulous Year of Conversations Between Reviewers and Authors

As book people with a proper sense of history, we’ve always been fascinated by the literary salons of 17th and 18th century Paris. These social gatherings of intellectuals and haute bourgeoisie were instrumental in fueling the revolutionary ideas of the Enlightenment, and played an important role in toppling the ancien regime and the French Revolution. And let’s not forget that most often it was women who served as salonnières—hosts with the all-important responsibility of choosing the guest list to assure the evenings’ conversations were both stimulating and convivial.

That same salonnière spirit is behind the FaceOff interviews you receive in every installment of Foreword This Week. From the hundreds of reviews we publish in Foreword Reviews, we search out the perfect author-reviewer combination to enlighten, educate, and entertain us as we eavesdrop on their conversation.

This week, we’re bringing you the Best of 2019—our favorite ten questions and answers from more than fifty interviews.

Happy holidays.

Reviewer Melissa Wuske Interviews Andrew T. Le Peau, Author of Write Better: A Lifelong Editor on Craft, Art, and Spirituality

How has the life of faith changed over your career? And what does that mean for writers who come from a faith perspective?

Our Christianized culture has faded away in much of Western society (though segments of the American South are exceptions). As with the digital revolution, this has had mixed results. Two opposite impulses seem to be at work at once. On the one hand is the impulse to be accepting of a greater range of religious belief and expression. On the other hand is the impulse to expunge religion from the public square rather than see it as having an equal (though not privileged) voice alongside others.

I think the impact generally has been to turn faith into just another preference, like toothpaste or being a vegetarian. One doesn’t suggest in polite company that we have been in touch with ultimate reality. Yet without a sense of the transcendent, our lives are so much flatter. Boredom then leads us to seek flashy but finally unsatisfying experiences.

The challenge for writers who want to express something of their faith is to vividly portray the world people experience in their everyday lives and at the same time communicate the deeper world beyond our senses. As others have noted, the interest in zombies, vampires, aliens, superheroes, wizards, indeed all of science fiction and fantasy, point to our desire to fill a landscape stripped bare by a secular, preference-driven mindset.

Reviewer Michelle Anne Schingler Catches Up with Paul Theroux, Author of On the Plain of Snakes: A Mexican Journey

How much planning goes into your trips, and why do you choose to travel that way?

I do quite a lot of advance preparation. I look at maps, I read a lot of the national literature. When I decided to go to Mexico, I read lots of Mexican novels, books about Mexican culture, Mexican life, histories—I plunged into them. And I looked at maps, all to figure out how best to write about Mexico. I also thought that I wanted to improve my Spanish, and I needed a message.

I had gone on a road trip to the Deep South (for my Deep South book, published in 2015)—to Arkansas, Mississippi, and Alabama and so forth, and I thought I’d also take a road trip to Mexico, and drive my own car. That posed a problem: people were saying “Don’t do it … It’s not a good idea.” You just disobey them; that’s what I did. I’d figure out how to do it. There were problems, obviously, but I worked out a method.

My motivation was Donald Trump saying that all Mexicans are rapists and murderers and that the border is strange and awful. I wanted to look at it myself. I want to destroy the stereotype. And to do that I read books, talked to people, drove my car, improved my Spanish.

When I set off, I was prepared, but I was also prepared for any random thing that could happen. I was driving alone, so if someone made a suggestion—“Go here, see that”—I changed my plan in an instant.

Reviewer Tanisha Rule Interviews Renée Watson, Author of Some Places More Than Others

Discovering roots is a major theme in the book. What do you see as being the biggest risk of a person not knowing, or being interested in, one’s roots?

We risk hopelessness, we risk stagnation.

I believe knowing where you come from can give a sense of hope, pride, and determination. And when I say “where you come from” I mean this literally and spiritually, with an understanding that sometimes our families are the people we choose. Sometimes, we have to look to people we haven’t met in real life—our ancestors, activists, artists—to find commonality and inspiration. If we don’t have that, if we don’t connect to a history, I think it’s hard to have a vision for oneself. Knowing the stories of the people who came before me motivates and encourages me to take what they left me and add on, leaving something better behind for the next generation.

Reviewer Claire Rudy Foster Interviews Joshua M. Ferguson, Author of Me, Myself, They: Life Beyond the Binary

Your memoir is a testament to the power of personal stories to create real change for marginalized people, like acknowledgement, protection, and support at the policy level. How do you hope to change the world with your book?

Thank you for saying that, Foster. You wrote in your review of the book that “queer pain is powerful, but queer joy will change the world.” The book is dedicated to my husband, Florian. The acknowledgements section is seven pages long. Queer joy around me has changed my life, and I am hopeful that the joy and love others find in their identities can help to change the world.

Peace and love. That’s what it’s about for me. If we can be recognized in society, protected and supported, then we can feel a little more free to be who we are in our personal lives. The policy level changes need to happen on all fronts. Recognition on identity documents is a very small part of the matrix of policy changes for trans people.

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews David Barrie, Author of Supernavigators: Exploring the Wonders of How Animals Find Their Way

Your book mentions that exercising the navigational skill we possess as humans could help us as we age, and maybe even affect the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. What types of activities do you recommend? What might people of any age who are “always getting lost” do to improve their sense of direction?

Yes, indeed. The parts of the brain that support human spatial navigation also seem to play a key role in other, purely conceptual forms of navigation. They seem to support our capacity for prediction, imagination, and even artistic creativity. So perhaps it’s not surprising that we use navigational metaphors so frequently. We speak of being “on top” of a subject, or “under the weather,” or “mapping a problem,” and so on.

The trouble is that our brain circuits shrink when they’re not used. Now that we’re becoming ever more reliant on our gadgets to solve our navigational problems, this not only means that our natural ability to find our way around is going to decay, we may also find that these other, more abstract but crucial functions are compromised, too. For the same reason, our capacity to cope in the face of Alzheimer’s disease—an increasingly common scourge that attacks the very same circuits—may well be reduced.

So yes, I really do think we should discourage our children (and ourselves!) from becoming totally dependent on electronic navigation. That means turning off the Satnav in your car and putting aside your GPS-enabled phone unless you really need to use them. It means learning routes by taking note of landmarks, and when necessary, plotting your position on an old-fashioned map. Quite simply, you need to start paying attention to everything that’s going on around you, just as people used to do! But I have to admit that it’s going to be very hard to win this battle when arguments of safety, speed, and convenience generally favor the other side.

Actually, there’s another objection to our increasing reliance on these gadgets—they put yet another barrier between us and the world around us. Instead of looking around, noticing where the sun is, or the patterns of stars in the night sky, or which way a river flows; instead of actually working out where we are and where we’re headed, we now just stare at our little glowing screens. We have become passive consumers of navigational information, traveling the world without ever really knowing where we are.

This is a new and dangerous form of alienation. Gadgets can, and do, fail. And there are many places where they don’t work. So just as I would encourage children to admire and respect the living things around them, I would also teach them to find their way around like our ancestors, making use of their sense and their native wits. To learn the “language of the earth,” as Rebecca Solnit has so beautifully put it. It’s not only safer, but a lot more fun!

Reviewer Katie Asher Interviews Lori Erickson, Author of Near the Exit: Travels with the Not-So-Grim Reaper

If you could abandon all previous knowledge and context, and choose a culture and/or religion based solely on its guidelines and theology, what would you choose, and why?

This question really stumped me. After thinking about it for some time, I’d choose not just one, but instead a blend of several traditions, though of course that’s just the sort of squishy theology that question #3 refers to. I’d put together an amalgam of Christianity and Buddhism with some nature mysticism thrown in. I’d love to live in a compound with Jesus and Buddha next door, and every Saturday evening we’d get together for a service with incense and bells and chant, and then we’d have a big party with wonderful food and invite everyone in who needed a meal. We’d spend the next day meditating in silence. And every year we’d do at least one wilderness trek where we’d commune with bears.

Reviewer Matt Sutherland Makes Baby Talk with Jenny Brown, Author of Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight over Women’s Work

What’s the one thing about the book or topic that you find interesting and noteworthy, but doesn’t get the attention it deserves?

Immigration has always been the primary US method for increasing population. But I think the government’s crackdown on immigrant communities has left the impression that the establishment opposes immigration, when in fact most employers and even most Republican lawmakers support immigration. However, they don’t want immigrants to have rights, which is why you see all this high-profile enforcement and terror. At the same time president Trump is trying to stop refugees from violence in Central America, he’s supporting a 30,000-person increase in the H2B guest worker program. Guest workers are ideal for employers, because they don’t have any rights on the job. They can be deported if they don’t work fast enough or object to dangerous working conditions or wage theft. And in the long term, they won’t be able to organize against injustice or vote, because as soon as their employer doesn’t need them, they can be kicked out of the country. Even largely pro-immigration Republicans such as Jeb Bush want to get rid of family reunification because, he says, parents and children of workers often need services such as health care and education. These thinkers are gleeful that working-age immigrants have been “raised on someone else’s nickel,”—US employers are getting workers without contributing to their upbringing. This is a huge ripoff of mothers, families, and communities in sending countries, but it is consistent with the desire of employers in the US to obtain workers without paying anything towards our social infrastructure.

Reviewer Mya Alexice Talks Female Transformation with Rebecca Solnit, Author of Cinderella Liberator

Was Cinderella Liberator inspired by a particular event or idea or more by the current political moment as a whole?

As I mentioned in the afterword, it was prompted by buying an image from a book in the San Francisco Public Library bookstore, one that showed Cinderella as a ragged but cheerful girl at work. I turned it over a while after I bought it and it had a bit of text on it, in which the fairy godmother and Cinderella are collaborating on transforming creatures.

“Here, my child,” said the fairy godmother, “is a

coach and horses, but what shall we do for a coachman?“

“I will get the rat trap,” said Cinderella.

That was rather exciting: here they were improvising together, here was Cinderella as an active participant. I thought that perhaps it always was a story about transformation, a sort of micro-Metamorphoses, and that with that as the operating principle it could be about the transformation that is liberation. One of the catch-phrases of Buddhism is “the liberation of all beings” and that works for the goals of this book.

Reviewer Anna Gooding-Call Interviews Leigh Calvez, Author of The Breath of a Whale

How do you maintain your emotional stamina despite the difficulty of environmental activity?

Environmental conservation is life and death. I came close enough to death myself that I understand this deeply. I don’t let myself spend too much time in the negative emotions, like anger and fear. If I start to feel guilty—as I do, I can go there in an instant—I go directly to the ponopono prayer that I discuss at the end of the book. I’m sorry, please forgive me, thank you, I love you. I just say that over and over. It’s like a meditation. I repeat it until I start to feel better, until I can start to feel that forgiveness. Sometimes this is a daily thing. I constantly remind myself to look at the beauty of the trees, the whales. It’s a choice, a constant choice, to pick beauty over fear or love over fear.

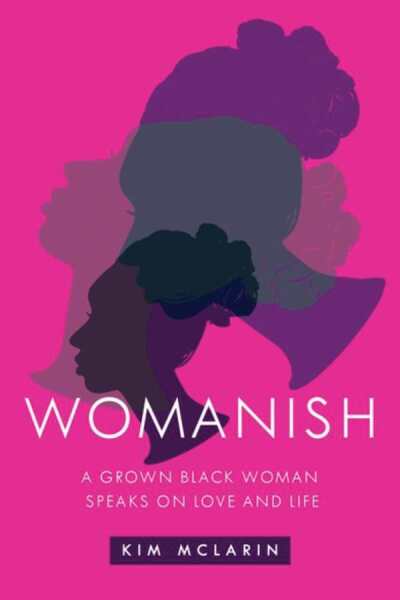

Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers Interviews Kim McLarin on Womanish: A Grown Black Woman Speaks on Love and Life

You use the term “womanish,” both in your title and at various points where issues around gendered social expectations are addressed. Feminist and womanish seem to share space in a Venn diagram, but I didn’t read them as perfectly synonymous. What’s the difference, if any, and what’s important for you about this term?

I came of age during Second-wave feminism. And because it was pretty clear that mainstream feminism was not for me, I never thought of myself as a feminist. I thought of myself as a Black woman, which, long before I heard of intersectionality, I understood as an identity and a personhood (though that personhood was so oft-denied, which was part of the identity) distinct into itself. So although I certainly share and support the political, cultural, and economic aims of feminism, I was just never interested in the term. Whereas, somewhere around the age of 40 or 45, I became very interested in the question of what it means to be a Woman. Not what it means to be female—what it means to be a Woman. Grown. Grown-Ass, if you want to get down into it. That’s what the old folks used to say when I was a child: “Oh, you think you grown, huh? You acting womanish!” Yes. Yes, I am. Womanish is not a stance or a position; it’s a declaration of attainment, a proclamation of arrival, an ululation. It’s weighty. And joyous. And earned. If that makes sense. It’s that great Lucille Clifton poem “Won’t You Celebrate With Me.” Actually, scratch everything I just said and read that poem. It defines womanish far better than I ever could.

Matt Sutherland