Under the Ocelot Sun

“no one leaves home unless home chases you … you have to understand, / that no one puts their children in a boat / unless the water is safer than the land.“

These words of Warsan Shire, a Somali-British poet and former Young Poet Laureate for London, are likely familiar to you. Her poem “Home” has been shared widely across social media and used in countless public spaces and charity campaigns since it was published in September of 2015, coming to speak to refugee crises around the globe as it vivifies the grief and trauma of displacement. For many, Shire’s words unlocked a tangibility to tragedies often perceived only through newspaper headlines and news footage—a terrible injustice that is happening in some far-flung “there” to “them.”

Though hardly a new phenomenon, Central American migrant caravans intermittently dominated headlines in the United States throughout 2017 and early 2018. Fleeing war, drugs, poverty, and famine, these refugees were not granted the same title or sympathy in the U.S. as public opinion afforded their global counterparts, instead demoted to criminals or illegal immigrants and regarded with fear and suspicion. But just as the power of language can be harnessed for ill, so, too, can the written word be a force for understanding and acceptance.

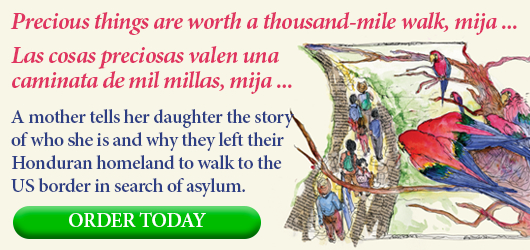

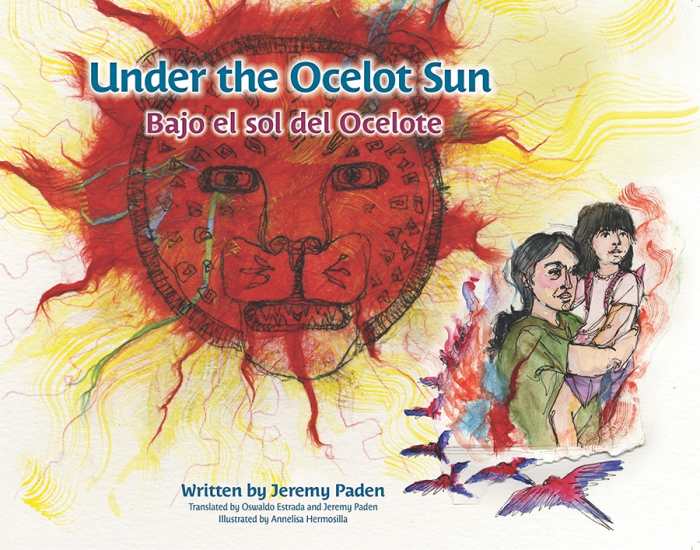

Jeremy Paden and illustrator Annelisa Hermosilla lend their pens to this cause in Under the Ocelot Sun, a story following a mother and daughter on the dangerous, hopeful journey toward the U.S. border from Honduras. Presented in both English and Spanish, Pallas Gates McCorquodale described it as an “emotional narrative [that] beseeches everyone, everywhere, to understand why some things are worth dying for” in her review for the July/August issue of Foreword Reviews, and we knew we needed to find out more about this timely title.

With the help of Shadelandhouse Modern Press (www.smpbooks.com), we connected with Jeremy and Annelisa for an interview. We hope you find their answers as insightful and inspiring as we did.

The book references a Nahua creation myth that serves as its inspiration: the myth of the Five Suns. We admit to being wholly unfamiliar with the myth, but were captivated by the magic it lent your story. Jeremy, how did you settle on this particular myth as your inspiration? Are there others you could see inspiring future books?

Jeremy: In my day job, I teach Latin American literature. Not only that, my specialty is Colonial Latin America. As such, in some of the classes I teach we read about Pre-Colombian cultures and peoples. Also, we read contemporary literature that uses these myths. So, I am very familiar with the myths of Mesoamerica and with how rural communities still pass on these myths—sometimes, it must be admitted, in fragments, and sometimes, even, depending on the community, there will be little to no memory of these myths. But, to be honest, I did not start with the myth of the Five Suns.

Instead, I backed into the use of this myth. I knew I wanted a story that spoke to identity, a story that would tie an urban family to the mountains they came from, and then further back through time. Grandmothers are keepers of cultural and familial lore. They are also, often, the keepers of family recipes. Grandparents ground children in who they are. They provide them with stories of the family, provide them with love, care, and food, and also teach them their first notions of right and wrong. I started, then, with the grandmother and with food. This, in turn, led me to the centrality of corn as the staple of life, which led me to the Mayan and Nahua creation stories. To sum this up, for me the grandmother/storyteller was the glue and from her came the kind of wisdom that grandparents pass on, a wisdom rooted in the old stories.

As to the final question, whether or not I see others in the future, I don’t know. I do have a full-length manuscript of poems that uses and plays with various Amerindians myths, from Nahua to Guaraní. These stories are always present in my mind.

Let’s be frank: this is not an easy topic for a children’s book. People fleeing war, drugs, and poverty in search of a better life is a difficult subject to approach for children, but you both handled it so deftly—reflecting and validating the harsh realities without talking down to the audience or overburdening them. Can you speak a little to the process of tackling this subject with a child audience in mind, Jeremy? And, Annelisa, what difficulties or questions did you have to resolve while illustrating the subject matter?

Annelisa: One of the biggest challenges for me was capturing the harshness of the situation without diving too deep into graphic violence. Children are not blind to injustice, but in an attempt to provide a safe space for kids to learn about and discuss these topics, my main goal was to present physical/mental/emotional struggle in ways that do not fall into morbidity, without romanticizing or pitying those who experience the brutality of fleeing their home.

I asked the team, my friends and family, children, colleagues, fellow artists, parents, and educators to give me some insight on my work. How does this illustration read? I included a lot of reds, oranges, and yellows in quite a few of the images, so it was important to know what these colors meant to others. I opted out of a couple early ideas because of how other people interpreted them.

Jeremy: You are right, this can be pretty heavy. But life is heavy. And children know that life is heavy. I think that children know and understand this better and more deeply than adults believe they do. I think as adults we forget this and try to protect children from this. Instead, we should find the way to have these conversations with children. I think children will and do surprise us with their empathy and wisdom.

That said, violence or difficulty shouldn’t be gratuitous. What harshness there is needs to be true to the matter at hand. Children throughout the slums of Latin America struggle with hunger and, even, drugs—especially in the form of huffing the fumes of various kinds of chemicals. The countries of Central America, for most of the twentieth century and now the twenty-first, have been the site of various wars. This violence is found in both the countryside and in the cities. But even in the midst of this violence there is love and beauty; humans are resilient. And all of us can handle multiple realities and emotions, even contradictory ones, at the same time.

The call I felt was to try to tell the story as truthfully and humanely as I could through story, not argumentative prose. Storytelling through lyrical language allows, I think, for one to focus on harsh realities and to do so in a way that is respectful of the reader’s sensibilities. And, certainly, Annelisa’s images, which she labored and worried over, do a good job of making the images concrete without being gaudy or lurid.

Annelisa, we loved the inclusion of topical newspaper articles in many of your illustrations—it added an immediacy to the story and reminded us to always consider the humanity behind the headline. Is this mixed-media technique often a feature of your work? What drew you to that technique?

Annelisa: Jeremy suggested a collage approach. I had previously made a mixed media triptych to be exhibited at a local gallery, and Jeremy asked if I would consider this technique for the picture book. The newspaper clippings were definitely the first element I thought of using. It was easily accessible at the moment. I just grabbed the old paper from my workplace before it got tossed out. Not only that, but newspapers add a sense of relevancy, especially when you see words that resonate with the subject at hand, kind of like saying “This is happening! It’s in the news,” and I thought that was the hammer I needed to nail down the message.

I am a huge fan of collage, although it is not heavily present in my artwork collectively. My art consists mostly of ink and some form of color (marker, color pencil, watercolor, crayon) or just ink. However, I love experimenting with various media and seeing how well each works with ink, so that’s where the mixed media comes into play.

Both the narrative and the illustrations seem to come from a deeply personal place; the passion you both had for this project is palpable in every word and stroke. You were also both branching out into children’s books for the first time. What about this project made each of you want to take that leap?

Annelisa: It is especially powerful to illustrate a children’s book. Kids have the power to become more compassionate, socially just, and empathetic than the generations before them. They can build a world of respect, tolerance, and diversity if they are given the tools to do so. The book is also a way for those who have experienced or are going through a similar narrative to feel seen—a way for them to know someone’s got their back. And for those who have not been through an experience like this, Under the Ocelot Sun is an opportunity to bring these issues to light.

Jeremy: My connection, as Annelisa’s connection, is very personal. My maternal grandmother was Puerto Rican. While she was already a U.S. citizen (Puerto Ricans have been since 1917), her marriage to my grandfather during WWII and her move from Puerto Rico to Texas was itself a story of immigration and overcoming cultural differences. Growing up, we always knew that she was not like the rest of the Texas family. Not only this, though, I was raised in Central America and the Caribbean. When we first moved to Nicaragua, it was the early 1980s and things in Nicaragua were complicated. One of my father’s best friends in Nicaragua immigrated to the U.S., crossed over in an unauthorized manner, and worked until amnesty was given in the mid 1980s, at which point he brought his wife and children over legally. My teenage years were spent in the Dominican Republic and I had many friends and family members of friends who immigrated to the U.S. or spent a good bit of time trying to immigrate. Now that I live in the States, Tracy, my wife, and I have worked with and befriended Sudanese, Syrian, and Latin American immigrants.

Annelisa: This story touched on a personal matter; family, friends, friends-of-friends … countless stories similar to this one that seem to never end. Not only here in the U.S., but I’ve also seen similar injustices in my home country, Panama. Immigrants who travel from different parts of the world fleeing poverty and violence, looking for a simple chance of survival, only to be met with prejudice and harsh immigration laws. I believe nobody deserves to be treated like an animal, no one should be criminalized for their skin, their ethnicity, their social background or their economic status. Under the Ocelot Sun was an opportunity for me, as an artist, to add my fist to the fight against injustice and I thank Jeremy, and Virginia and Stephanie (Shadelandhouse Modern Press) for their amazing trust.

Are there any other books or collections in the works for you, Jeremy? Did you enjoy turning your skillset to picture books, Annelisa, and is that something you’ll pursue going forward?

Jeremy: When my daughter was younger, I wrote a poem about a tiny bear that looked like a rabbit and a rabbit that looked like a bear who were bullied by their own groups, bears that look like bears and bunnies that look like bunnies. When they found each other, they became fast friends. At the time, I thought it would be nice to illustrate it, but I didn’t know how to go about it. So, aside from my daughter drawing pictures for it, I never gave it much mind.

I do like, and have always liked, how picture books allow for a coming together of both the narrative and lyrical elements of writing. I have also always liked the relationship between image and word that picture books celebrate. And, while I don’t know what the next picture book might be, I am very open to the idea of working on another such project. Shadelandhouse Modern Press and Annelisa have been such wonderful collaborators.

I should also say, it was a great pleasure for me to be able to work with Oswaldo Estrada on the translation. Oswaldo and I met years ago at a conference in Colombia when we were both young academics at our first teaching appointments. Over the years we have kept in touch and both of us have ventured beyond academic writing into the creative sphere. He writes fiction. I write poetry. One of the greatest temptations for me as a poet who writes in both English and Spanish is to be an unfaithful, overly creative translator. In this case, when I translated the book into Spanish, I did two translations, a faithful one and a more experimental one. I sent Oswaldo the crazier one. He gently chided me and sent me his own version, which was much closer to the first translation I had done. The register of his diction was spot on. I made a few changes based on my first translation. I am forever grateful that he did what he did. I would’ve gone with the more creative translation, which I am convinced would have gotten in the way of the story. Among other things, I think Oswaldo’s practice of writing fiction helped him find the right tone for the Spanish.

Annelisa: Illustrating Jeremy’s book has definitely strengthened my interest in illustrated literature, especially children’s books. It’s an area of art that allows me to share my skills with a larger community. Picture books spark conversations and teachable moments for all ages, which is awesome because I am absolutely in love with communication and learning.

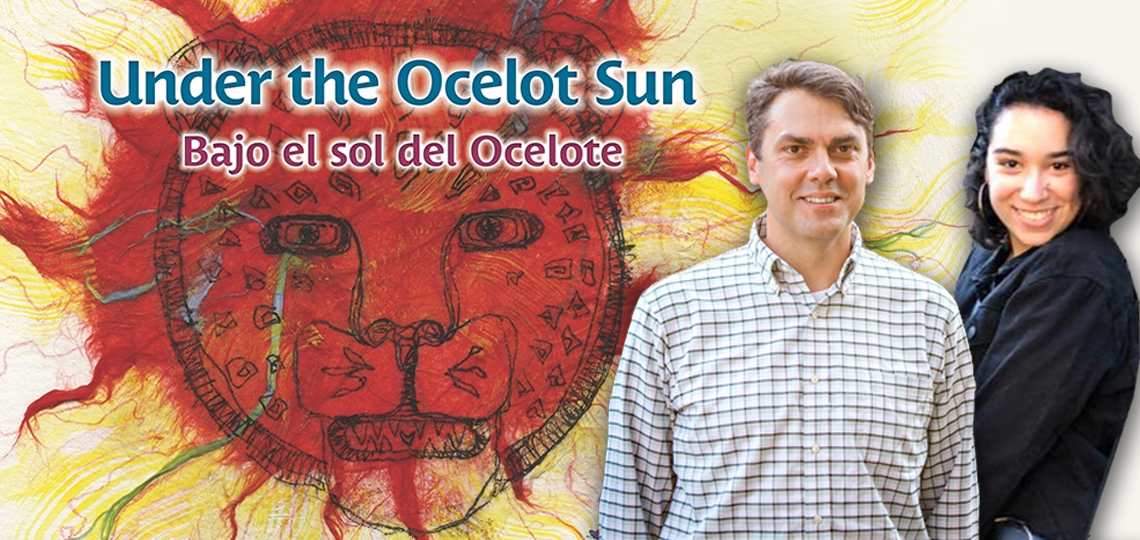

Jeremy Paden was raised in Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic. He is a poet, translator, and professor of Latin American literature at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. He is the author of three collections of poems. Among these, ruina montium, about the 2010 Chilean mine collapse, has been published in both English (Broadstone Books, 2016) and Spanish (Valparaíso, 2018). He is also the translator for various poets from Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Spain.

Annelisa Hermosilla was raised in Panama City, Panama, and moved to the United States to study art at Transylvania University. She currently lives in Virginia and is a promising artist at the beginning of her career. This is her first picture book.

Under the Ocelot Sun

Bajo el sol del Ocelote

Jeremy Paden, author, translator

Annelisa Hermosilla, illustrator

Oswaldo Estrada, translator

Shadelandhouse Modern Press

Hardcover $18.95 (44pp)

978-1-945049-16-3

In this bilingual book, a mother shares the story of her beloved homeland and its struggles to survive growing political corruption, violence, and poverty. She weighs the risks and possible rewards of immigration in bittersweet verses. They alternate between English text in azul and Spanish text in rosa oscuro. Haunting, beautiful watercolors and pen and ink drawings highlight the proud traditions of the Central American Nahuas. This emotional narrative beseeches everyone, everywhere, to understand why some things are worth dying for.

PALLAS GATES MCCORQUODALE (June 27, 2020)

Danielle Ballantyne