Understanding Islam: 8 Books Introduce a Diverse World Tradition

Perhaps you’ve seen the Onion headline: Man Already Knows Everything He Needs To Know About Muslims. The wry implication is that many people who are very vocal about Islam have deliberately avoided learning much about its complexity. We can now include certain presidential candidates in those ranks.

Yet Islam is an enormous world religion, with over a billion-and-a-half adherents worldwide. It should be no surprise to hear that there’s incredible diversity amongst the world’s Muslims, not just across national borders, but on a community-by-community basis. We’ve compiled a list of books we’ve reviewed, and loved, on Islam and Muslim cultures to flesh out some of these nuances.

We’ve got religious history here, Qur’anic interpretation, basic introductions, a book on the hijab, and one on Muslim art. Whatever your particular interest, we’re confident that there’s a title here that can satisfy your curiosity. And, at the very least, you’re now armed with titles for next time you encounter a version of the Onion’s ubiquitously incurious Man.

Who Speaks for Islam?

What a Billion Muslims Really Think

Dalia Mogahed

John L. Esposito

Gallup Press

Unknown $22.95 (230pp)

978-1-59562-017-0

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

There are inherent difficulties in understanding what people within other cultures believe. This is especially true when it comes to American perceptions of the world’s 1.3 billion Muslims. In Who Speaks for Islam?, Georgetown University professor John Esposito and the Gallup organization’s Dalia Mogahed try to expand mutual awareness by presenting a wealth of survey data about the Islamic world.

The book builds on the foundation of a long-term (2001-07) Gallup research study that, according to the authors, used a random sampling method to represent the beliefs of more than 90% of the world’s Muslims. The discussion of the data focuses on topics of wide interest to Western governments and publics alike: political beliefs, radicalization, religious views, and cultural matters (such as the role of women in society). Informed by Esposito’s scholarly expertise, the narrative avoids delving too deeply into esoteric issues, thus maintaining appeal for a more general audience than a purely academic tome. The authors explain basic facts about Islam to provide context for the data before citing the survey results and offering their interpretation thereof.

Some of the findings may shock readers. For example, a significantly higher percentage of politically radicalized Muslim respondents (as contrasted with politically moderate Muslims) agreed that “moving toward greater governmental democracy” would foster progress in the Islamic world—not the view of Muslim extremists portrayed in the mass media. Results from the other side sometime surprise, too. In one cited survey, nearly one-quarter of Americans say they would not want a Muslim as a neighbor.

Readers interested in raw survey data or Gallup’s research techniques will be disappointed; the results of the various questionnaires usually appear without supporting information and the appendix offers few insights into the genesis of the research project and questionnaire design. For the general reader, however, this is a good thing. The text flows well, offering only enough survey data to make a point without burying the message in tables of numbers or statements about statistical significance. Who Speaks for Islam? is a useful book with more than a few surprises about what Muslims—or at least certain subgroups of Muslims—believe about various political, religious, and societal issues.

DAVID PRIESS (February 25, 2008)

Easily Understand Islam

A Collection of Articles

F. Kamal, author, compiler

Desert Well Network

Softcover $19.95 (300pp)

978-1-59236-011-6

Buy: Amazon

The basic tenets of Islam remain mysterious to many Americans despite the intense media focus on Muslims since September 11, 2001. Even fewer people are familiar with how mainstream Muslims view the Bible or how they apply the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad’s sayings to contemporary issues. This collection of essays addresses these topics with two audiences in mind: readers new to Islam, and Muslims seeking an informed Islamic perspective on the religion’s relevance for present-day problems. The editor (who holds degrees in engineering and business, and has studied Islam widely) brings together a volume that delivers more value to the latter group.

Because non-Muslims often fail to understand the basic elements of belief and practice that bind Muslims together, Kamal begins by tackling common misconceptions. He disputes, for example, the notion that the Prophet Muhammad wrote the Quran (which Muslims instead accept as divinely inspired). The five “pillars” of Islam, such as the requirement to pray five times a day, and other basic articles of faith receive succinct attention. Many previously published introductions to Islam do a better job covering these topics, but Kamal deserves credit for creating a solid common foundation for all readers, and including lists of Muslim virtues from the Quran and Muhammad’s sayings.

This book’s primary worth lies in the more adventurous chapters by other authors. In a chapter titled “The Quran and Modern Science,” Zakir Naik raises fascinating similarities between Quranic verses and developments in modern science, ranging from astronomy to zoology. As a case in point, he notes that the Quranic verse “And the earth, moreover, hath He made egg shaped” seems to describe the true shape of the planet even though flat-earth theories prevailed during the seventh century, when the Quran was revealed. Jerald Dirks provides another highlight in “Common Ground: Judaism, Christianity and Islam.” By comparing and contrasting the founding texts of these three faiths in a straightforward, easily digested account, Dirks goes a long way toward helping Muslims, Christians, and Jews understand both their shared tradition and their differences.

The contributors do not shy away from contentious topics: the book addresses inconsistencies in the Bible, logical difficulties with the Christian concept of the Trinity, and the opportunity for Islamic teachings to help address social problems in the United States. These chapters may appeal more to Muslims than to readers new to Islam.

By ambitiously aiming both to introduce Islam and to tackle difficult theological matters from an Islamic perspective, this book differentiates itself from many less demanding books about Islam. Those who seek only an introduction to the religion may be better off elsewhere, but readers eager to jump into more advanced treatments of Islam, its place in the monotheistic tradition, and its application to contemporary issues will find Easily Understand Islam a rewarding book, sure to spark new thoughts and vibrant discussions.

DAVID PRIESS (January 5, 2007)

What Is Veiling?

Sahar Amer

The University of North Carolina Press

Hardcover $28.00 (312pp)

978-1-4696-1775-6

In Amer’s able hands, the often feminist, anti-colonist nature of veiling is brought to light.

Preeminent professor of Islamic studies Sahar Amer returns with a work which seeks to demystify a looming symbol of Islam: the veil. In prose that is approachable and sympathetic, and with research spanning nations and centuries, Amer’s project manages to be both comprehensive and illuminative.

Amer’s presentation of the subject begins in a logical place, by examining veiling in the context of the Qur’an. She reveals that it’s not a significant topic. Rather, the tradition of modest dress arose later, among those who translated and interpreted the Qur’an and hadith, and as a matter of jurisprudence. Such chapters invaluably introduce Muslim history and practice in a manner useful to beginning and veteran historians alike, placing the veil in context with elegance.

The rest of Amer’s project works to challenge Western notions—those which label veiled Muslim women “oppressed” and call societies that seek to “liberate” them. Amer shows that the way the West has traditionally approached the veil has the dual effect of sexualizing and rendering Muslim women alien, not to mention uniform.

Cultural histories from across the Muslim world are made to stand in contrast to such monochrome presentations. Amer explores progressive Islam in both modern and early incarnations, showing that the veil has often been assumed as a means of self-expression and protection. The idea that the veil is most often prescriptive is neatly turned on its head.

Contemporary veiling, Amer shows, is more often a means of asserting individuality and choice or solidarity with a global sisterhood. This is particularly true of veiling in cultures hostile to it: “[The veil] is a mark of inner strength, courage, and faith precisely because it is so misunderstood.” Later chapters explore current trends in hijab-friendly fashion and intelligent cultural portrayals, highlighting additional forms of veiled empowerment.

Amer’s project successfully controverts the erasure of Muslim women’s experiences, which tends to occur in discussions of the veil, both in nations that require its most conservative expressions and in those that regard it as a symbol of oppression. Her work honors diversity among Muslim women in all national contexts, challenging what she calls the violence of their silencing.

What Is Veiling? is an important work that stands to advance multicultural conversations and is a must-read for all those who wish to intelligently approach the subject of Muslim women and autonomy.

MICHELLE ANNE SCHINGLER (August 27, 2014)

Introduction to Traditional Islam

Foundations, Art, and Spirituality

Jean-Louis Michon

World Wisdom

Softcover $23.95 (168pp)

978-1-933316-51-2

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Because most introductions to Islam focus their attention on the religion’s history—with particular emphasis on the Prophet Muhammad and the sacred foundation of the Quran—readers seeking a broader examination of Islamic culture in a religious context have been largely disappointed. General audiences too often must either choose an “art book” that neglects the religious bedrock of Islam or pick a work concentrating on the latter but giving short shrift to artistic customs and practices that underlie many Muslim communities.

French scholar Jean-Louis Michon recognizes this gap and fills it capably with Introduction to Traditional Islam: Foundations Art and Spirituality. Using the development of culture in typical Islamic cities as a thread he describes the principles of faith art and architecture music spirituality and mysticism in the world’s second largest religion. In so doing Michon explicitly eschews investigation of “fundamentalist” and “political” Islam which he dismisses as aberrations from the enduring foundations and principles of what he calls “traditional Islam.”

The opening section which covers the tenets of Islam manages to walk the fine line between brevity and adequate treatment of the basic elements of religious practice. Michon covers the Quran the Sunnah (customs of the Prophet Muhammad) and Islamic jurisprudence efficiently before relating the five “pillars” of Islamic belief—expression of faith prayer fasting alms-giving and pilgrimage—and the foundations of the Islamic city in an equally economical fashion. This section of the book like those that follow are liberally illustrated with intriguing full-color images of mosques and city scenes from Islamic locales ranging from Spain to Niger to Uzbekistan (and including most countries in between).

The real comparative advantage of Introduction to Traditional Islam begins in Part II “The Message of Islamic Art.” Here Michon moves beyond mere description to analyze how various art forms—architecture gardens mosaics representational art handcrafts and especially calligraphy—inform and are informed by the context of the Islamic city and Muslims’ spirituality. Standing out in this section is Michon’s correction of the oft-repeated misunderstanding that the Quran bans the human figure in art. He usefully relates that many observers assume such a prohibition when in fact it is traditional Islam’s revulsion at “seeing man substitute himself for the Creator in wishing to imitate natural forms” that explains the rarity of portraits and related representational art in many Islamic cultures.

Michon puts to rest a similar myth in the following section pointing out that although many conservative Islamic communities through the ages have outlawed musical expression neither the Quran nor the Sunnah outlaw the practice. His assessment of Islamic philosophers’ spiritual arguments for and against music is particularly enlightening. The discussion leads to a fascinating overview of instruments rhythms melodies and vocal arts in traditional Islamic societies. He wraps up the book with an extensive analysis of the theory and practice of Sufi mysticism the movement within Islam that incorporates music most fully into its religious rituals.

Introduction to Traditional Islam is at its best when describing the sights and sounds of Islam. Michon—drawing on his experience working in Islamic countries for various United Nations agencies and as a freelance translator/consultant—wisely includes nearly 300 illustrations that bring the text alive and make the book a joy to flip through time and time again. He clearly celebrates the cultural heritage of Islam serving more as a sympathetic observer than a critical appraiser and writing with an enthusiasm that will draw most readers in.

The book is not without shortcomings however. Especially in the early pages the placement of many illustrations is confusing as they do not relate directly to the text and the reader also wonders why Michon introduces scores upon scores of Arabic terms (far too many for a general audience). He also tends to make wide-reaching claims about Islam and Muslims often conflating diverse societal experiences into generalizations that obscure more than they reveal. He acknowledges for example that “the unity of the Muslim community is more than ever compromised by national rivalries and ideological dissensions which rarely have anything to do with the ultimate interests of believers.” But with the exception of lengthy descriptions of various regions’ musical genres he rarely devotes enough attention to the wide differences that characterize contemporary life in much of the Islamic world as much as his idealized vision of the “ traditional Islamic city.”

These points aside Introduction to Traditional Islam stands out among the many introductory works on the Islamic faith for its careful consideration of cultural context and interweaving narratives among Muslim artists architects musicians and religious authorities especially within the urban setting. It will make a rich colorful addition to any display or collection on Islam.

DAVID PRIESS (March 12, 2009)

Coming to Terms with the Qur’an

Andrew Rippin, editor

Khaleel Mohammed, editor

Islamic Publications International

Hardcover $39.95 (384pp)

978-1-889999-48-7

Unlike the sacred texts of Judaism and Christianity, which are dynamic and open to the possibilities of interpretation (although the extent to which different groups accept interpretations varies), the Qur’an, Islam’s sacred text, has long been regarded by Muslims and non-Muslims as one that is never open to such treatment.

In this festschrift, Mohammed and Rippin gather fourteen essays in honor of Islamic scholar Issa J. Boullata, a professor at the Institute of Islamic Studies at McGill University in Toronto. Boullata has spent his life challenging long-held ideas about the Qur’an and encouraging generations of scholars to situate the Qur’an in its historical and cultural context. Contributors to this volume include students Boullata has mentored as well as his friends who have discussed these issues with him over the years.

The book is divided into three sections. Part One identifies problems in reading the Qur’an and includes essays on topics from the concept of reform in the Qur’an to the uses of metaphor and authority. Part Two focuses on the Qur’an in history and includes essays that examine the Dome of the Rocka spot sacred to Muslims, Jews, and Christians, as well as the dialectics of the Sunnis and Shi’ites and their readings of the book. Part Three examines the Qur’an in the modern world, especially the ways various teachers have approached the text in Egypt, Syria, and India.

Any collection of essays is bound to be uneven, and this one is no exception. However, this is a quibble, for the works by this group of scholars challenge traditional thinking about the Qur’an and encourages close reading and thinking about the texts. For example, in his essay, “The Qur’an, Chosen People and Holy Land,” Seth Ward, who teaches Islamic history and religious studies at the University of Wyoming at Laramie, engages in a close reading of several hadiths (verses) to demonstrate that “many verses in the Qur’an support the chosenness of Israel, and even God’s specific promise of the land to the Israelites.” Ward encourages this close reading of the text as a means of fostering Muslim—Jewish dialogue.

General readers may have difficulty following some of the essays since the authors are speaking to themselves as much as to a broader audience, and they often use specialized language. Overall, however, the essays are thoughtful and provide fresh insights into the nature of Islam and the character and authority of the Qur’an.

HENRY L. CARRIGAN (May 7, 2008)

Universal Dimensions of Islam

Studies in Comparative Religion

Patrick Laude

World Wisdom

Softcover $23.95 (164pp)

978-1-935493-57-0

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

In Universal Dimensions of Islam Editor Patrick Laude compiles sixteen scholarly articles on the aspects of Islam that matter most to a Western audience in today’s particularly tense political climate. Ideas of universality, Islam’s perspective on other faiths, interfaith dialogues, the role of love in the Qur’an, and detailed explorations of Sufism make up a significant portion of the collection, along with a smattering of unique but absorbing studies of Qur’anic ideals and linguistic meditations. Though aimed at a scholarly audience, this collection pricks at the root of Western discomfort with Islam—a faith that is seemingly foreign and incompatible with Western ideals.

The spirit of the collection is perhaps what is most impressive. A central goal of the journal—and by extension this collection—is to underline the common threads stitched through the vast array of religious paths. Laude’s careful selection of articles points to a desire to provide readers with a clear and accurate understanding of Islam’s system of belief and how it coincides and even upholds the truths held sacred by other faiths. Furthermore, Laude is focused on presenting a collection that shows through individual studies how Islam is “intrinsically equipped to address universal human predicaments.” He stresses, and the essays in his book support, the fundamental belief of Oneness and Unity as a central factor in interpreting the universal appeal of Islam.

Michael Oren Fitzgerald’s essay, The Universal Foundations of Islam, offers readers a study of how Islam views other faiths. Through a close study of the main sources of Islamic beliefs (The Qur’an and Hadith), Fitzgerald shows how other faiths (particularly Christianity and Judaism), despite their differences, are recognized, validated, and in many ways hold the same fundamental beliefs of origin and Prophethood. This element of continuity—that the same unifying message has been sent (and re-sent) through various faiths, including Islam—reverberates through the other essays, with both unity and continuity stressed as important factors in recognizing Islam as a force of change in the modern world.

The book places heavy emphasis on Sufism—in many ways the most attractive and accessible strand of Islamic studies for Westerners. Its mystic ideals of journey towards spiritual climax and the individual struggle of the heart toward unity and spiritual calm are discussed at length and aim to display the accessible nature of Islam’s take on personal religious paths. The collection also offers unique meditations on themes of love and linguistics (William Chittick’s The Koran as the Lover’s Mirror and Rene Guenon’s enigmatic Mysteries of the Letter Nun) offer a dose of this absorbing style of study. This variety of content further emphasizes the goal of expressing Islam as a faith with universal dimensions.

Perhaps it also reflects the general movement away from studies that focus only on orthodox practices and instead places emphasis on interpretations that reveal new perspectives. It favours an approach that explores both traditional and alternative forms of Islam (and other faiths) through the lens of personal experience while utilizing the power of academic distance.

Eclectic and a testament to the highest caliber of research and writing, Universal Dimensions of Islam will appeal to scholarly audiences in the fields of comparative religion, politics, and interfaith studies.

SHOILEE KHAN (April 1, 2011)

Lost in the Sacred

Why the Muslim World Stood Still

Dan Diner

Steven Rendall, translator

Princeton University Press

Unknown $29.95 (226pp)

978-0-691-12911-2

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

When the first Arab Human Development Report (AHDR) was issued in 2002 it caused much soul searching. The report a project of the United Nations was compiled by Arab intellectuals sociologists and economists. Its unflinching assessment of the three benchmarks for development—knowledge freedom and women’s empowerment—showed that there were endemic problems. Poor technological and scientific development poor educational levels non-existent or weak political institutions (unions and professional organizations) overbearing governments and the exclusion of women from the economic and political spheres were all widespread in Arab nations.

Diner a professor of modern history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the director of the Simon Dubnow Institute for Jewish History and Culture at the University Leipzig Germany analyzes how the Middle East which led in cultural mathematical and scientific innovation during Europe’s Dark Ages lost momentum. His books include Beyond the Conceivable: Studies on Germany Nazism and the Holocaust; Cataclysms: A History of the Twentieth Century from Europe’s Edge; and America in the Eyes of the Germans: An Essay on Anti-Americanism.

Following World War I the Ottoman Empire was divided by the European victors. The Republic of Turkey was formed and its secular government abolished the offices of the caliphate. The caliph was seen as the successor to the prophet Muhammad and was the political leader of the Islamic world. Turkey’s decision still influences Muslims worldwide and is considered by some to be an abomination.

Diner believes that the preference for oral transmission of the Koran and the difficulty in learning high Arabic (as opposed to spoken Arabic) meant that the Arab world was slow to embrace the printing press. According to Diner “Islamic purists saw these modern machines as work of the devil challenging God’s control over time. They challenged both belief and believers. Such speeding up of the world’s pace could only end badly.” That led to a sharp partitioning of knowledge between the educated and the uneducated. He asserts that the interpretation of the Koran as the perfect word of God with nothing missing nor extra and the desire of some pious Muslims to achieve perfection by living as the prophet Muhammad did in sixth and seventh centuries means that people must always look to history for answers.

Diner’s book is a deep and thorough analysis of the causes of the problems identified by the AHDR that will be of interest to followers of Middle Eastern history and politics and those looking to under-stand the differences with the West.

DEIRDRE SINNOTT (February 13, 2009)

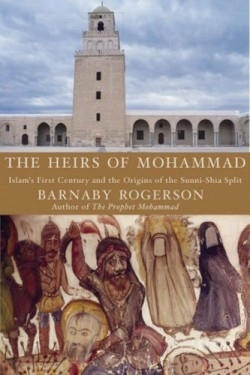

The Heirs of Muhammad

Islam’s First Century and the Origins of the Sunni-Shia Split

Barnaby Rogerson

Overlook Press

Unknown $27.95 (432pp)

978-1-58567-896-9

Buy: Amazon

Recent explosions, assassinations, and kidnappings in Iraq are the latest gruesome outgrowths of the fourteen-centuries-old divide between Sunni and Shia Muslims, which began in the wake of the Prophet Muhammad’s death in the year 632. Shia Muslims share with the majority Sunnis the central tenets of Islamic faith—including veneration of Muhammad as the last Prophet from the God of Abraham and Jesus—but differ in their legal customs and their steadfast belief that Muhammad’s family line was best suited to succeed him after he passed away. It has been difficult for the general reader to learn the full story behind this schism. Books on the topic often either rely on stereotypes and shallow analogies, thus failing to capture the intensity of the era, or slide into excessive erudition, thus missing the forest for the trees.

The author successfully avoids both extremes. This new work stands as one of the most readable and engrossing descriptions of Islam’s swift seventh-century expansion across the Middle East and North Africa, the personalities who oversaw the community’s growth, and the genesis of the Sunni—Shia split. Rogerson—who has written a biography of Muhammad and several travel-related books on North Africa—brings these momentous times alive through colorful prose, keeping the book extremely accessible to the general reader. His delicate balance of the Sunni and Shia narratives reflects his accomplished efforts “to honour both traditions and to sit like a tailor darning together two pieces of cloth into one.”

The first section covers Muhammad’s relationships with his closest companions, including his wives and the men who would become the first four Caliphs, or “successors,” after the Prophet’s death: Abu Bakr, Omar, Uthman, and Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law Ali. Special attention is given to Muhammad’s favorite wife Aisha and her relationships with each of these future caliphs. Rogerson skillfully tells how generations of Muslim legal scholars used a few Quranic verses that appear to focus rather specifically on the conditions of Muhammad’s household in Medina to constrain Muslim women in ways that have remained in force in some regions for centuries. Conveying the remarkable agreement between Sunni and Shia Muslims when it comes to the life of Muhammad, Rogerson also points out that differences between their two accounts begin at the moment of the Prophet’s death. Sunnis believe that Muhammad left this world with his head in the lap of Aisha; Shia claim that he passed away in the arms of Ali. Rogerson asserts that both could literally be true.

The rest of the book chronicles the all-too-few decades that passed before rising tensions within the rapidly expanding Islamic community dashed these hopes for unity and harmony. Rogerson brings the epic times of Islam’s spread under the four “rightly guided” caliphs alive with tales of clashing personalities and political intrigue. The subtext throughout is the belief among many Muslims (who later became the minority Shia) that Ali—due to his bloodlines and his close ties to the Prophet—was the natural heir to Muhammad’s place at the head of the Islamic community. Shia still rankle at the early Muslims’ willingness to grant leadership status instead to three others before finally selecting Ali in 656. Rogerson’s prose captures the ratcheting tension that led to outright war when Aisha led a rebellion against Ali, a fateful conflict that led to Ali’s death in 661 and eventually the disastrous Sunni—Shia schism.

Rogerson tells stories that both educate and fascinate. His chapter on the weapons, equipment, and tactics of the Muslim army, for example, rewards the reader with its rich detail. He dispels the notion that Muslim armies rode camels during combat. Instead, Arab soldiers often entered skirmishes on horses—which the warriors kept fresh for battle by encumbering camels instead during marches across vast distances. Rogerson also thoughtfully includes list of key dates and characters, nine original maps, and seven tables—which help clarify the intertwined family trees of Muhammad and his companions.

The book’s very success exposes its only real shortcoming. By drawing readers so effectively into the personalities and crucial events of Islam’s earlier years, Rogerson certainly will spur some readers to seek out his sources. Although the book includes a useful seven-page list of books that address topics ranging from Islamic theology to frankincense and myrrh, it lacks footnotes or endnotes to tell the inquisitive reader the sources for the specific facts that make this book such a fruitful volume. Nevertheless, Rogerson’s skill at making such a complicated history understandable leaves readers with a valuable account of the intra-Muslim divide that will appeal to those interested in learning more about the roots of some of today’s most intractable conflicts.

DAVID PRIESS (February 8, 2007)

Michelle Schingler is associate editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow her on Twitter @mschingler or e-mail her at mschingler@forewordreviews.com.

Michelle Anne Schingler