What Is Literary Fiction? Try These 10

Literary is a genre that is difficult to define, but we’ll give it a shot anyway. They’re books that make you want to submerge yourself in the words, to peel back the layers and examine each one. They’re captivating stories that stay with the reader long after the final page has been turned.

However you define literary, we think you’ll agree that these selections from our Summer 2016 edition more than qualify. Feel free to stay as long as you want as you browse these reviews of new independently published literary fiction.

A Seeping Wound

Darryl Wimberley

L’Aleph

Softcover $24.72 (312pp)

978-917637036-0

Buy: Amazon

A Seeping Wound is a dark story of human cruelty, and an ode to the preeminence of the human spirit.

In his arresting novel, A Seeping Wound, Darryl Wimberley forcefully chronicles life in one of the many slave camps of the rural American South in the early twentieth century—a place of persistent violence and evil, though it also hosts moments of human kindness.

Martha LongFoot is the story’s narrator, a half Muscogee Indian raised in the camp. She is also the camp’s medicine woman, a hard-won status that keeps her safe from the sexual violence that pervades the place. Martha comes across as a character with dimension who is worthy of respect. Her robust narrative, enhanced by her powerful vocabulary and occasional biblical references, is compelling, if it sometimes strains credulity. She begins the book angry and distrustful of white people, and ends the tale by saving white folks who are unjustly enslaved. Martha brings some closure to the experience by asking “Why does one wound heal while another festers?”

Other characters in A Seeping Wound are less complex, including the ruthless Captain Riggs, who runs the turpentine camp. This man, and the thugs working for him, are predictably violent, uncaring, cruel, and unchanging. Veteran Prescott Hampton, though, shines, and he is set up in the narrative as a contrast to Martha, as a camp outsider. He comes from New York searching for his sister and brother-in-law, who are enslaved in the turpentine camp. Where Martha is poor, uneducated, and surprisingly literate, Hampton is educated and comes from a financially comfortable family headed by his father, a journalist.

But, Hampton and Martha are commonly flawed—each suffers from a seeping wound that must be healed. Wimberley adroitly uses this wound image as both a cause of pain and a source of productivity, whether in a pine tree being tapped for sap or a human gashed by the vicissitudes of life.

Historically accurate, A Seeping Wound is a dark story of human cruelty, and an ode to the preeminence of the human spirit.

JOHN SENGER (May 17, 2016)

A Single Happened Thing

Daniel Paisner

Relegation Books

Softcover $16.00 (235pp)

978-0-9847648-3-9

Buy: Amazon

Paisner deftly uses the technique of grounding otherworldly fiction in everyday reality.

Daniel Paisner’s A Single Happened Thing is an engaging novel that weaves past and present with baseball and life, in a tone of surety and warm humor. Set in the last years of the 1990s, the story presents David Felb, a self-professed everyman with few illusions about his place in the world.

A book publicist in Manhattan, Felb works to promote the accomplishments of others at a job he’s had for twenty years. Devoted to his wife and daughters, trite midlife crises involving mistresses or red sports cars are unthinkable to him. Nonetheless, while on a business trip to Philadelphia, lifelong baseball fan Felb takes a break and goes to a Phillies doubleheader. There he crosses paths with the spectral incarnation of Frederick Dunlap, a Philadelphia-born baseball phenomenon who, despite a remarkable career, died penniless and alone in 1902.

Dunlap’s presence in Felb’s life has unexpected resonance. There is his own bewilderment, particularly when Dunlap shows up for subsequent visits, and there are the aftershocks that begin to trouble his marriage. Felb’s wife, Nellie, is a highly capable nurse, but in her pragmatic need to heal, she refuses to allow the possibility of other dimensions. Despite the fascinating nature of Felb’s conversations with Dunlap and the tangible souvenir of Dunlap’s frayed calling card in Felb’s wallet, Nellie insists that her husband see a psychiatrist and start taking antianxiety medication.

Paisner deftly uses the technique of grounding otherworldly fiction in everyday reality, keeping Felb’s interactions with Dunlap subtle while creating a backdrop of late-twentieth-century details like leftover Chinese food, ESPN, and dial-up Internet connections. Felb’s spirited teenage daughter, Iona, also a baseball fan and softball player and “always up for a catch,” becomes a willing accomplice in the Dunlap mystery, accompanying her father to the Cooperstown Hall of Fame and an old-school league game in Central Park. These elements combine to create the intriguing effect, as Paisner writes, of lives entwined “like the dovetailing waxed red threads stitched into the baseball … tossed to me some hours earlier.”

MEG NOLA (May 27, 2016)

A Well-Made Bed

Abby Frucht

Laurie Alberts

Red Hen Press

Softcover $16.95 (302pp)

978-1-59709-305-7

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

In this compelling story, the characters change, and some grow, through choice and consequence.

In A Well-Made Bed, coauthors Abby Frucht and Laurie Alberts use strong and complex characters and an almost campy plot device to explore how two young women, both raised in strict households outside of the mainstream, react when faced with temptation.

Jaycee was raised 1800s-style, at Hillwinds Living History theme park. Skilled in churning butter and slaughtering pigs, she doesn’t know the difference between a library card and an ATM card. Noor, the well-educated and beautiful daughter of Pakistani immigrants, is always aware of being an outsider and closes in on herself: “In Noor’s book, if you were going to lose something, it was better not to have it … better not to want it, either.” Both dream of escape: Noor, from debt and a disappointing marriage; Jaycee, from Hillwinds Living History. Each learns of a betrayal by a trusted loved one and responds by shaking off her usual constraints and seizing the illegal, yet potentially lucrative, opportunity that comes her way, with off-kilter justification. According to Jaycee, “You can’t say no to these things. You have to accept what life offers, not turn it away.”

Strong secondary characters further illustrate gradations of morality. Hil, Jaycee’s father, has built his entire identity on a fraud, while Hannah, Jaycee’s mother, merely chooses not to see things. Perhaps the most genuinely honest and insightful character is sometime drug dealer Gerry, who observes, “Little Noor Khan, you’re just scared. Scared to care.”

The tale of these two inept and oddly paired criminals is often humorous, as when Jaycee snorts coke “through a hollow reed from a cobwebbed Christmas wreath she’d made from cattails in one of the Hillwinds school workshops.” Fate scatters temptation like dandelion seeds. As Noor states, “That’s all it took, a couple of minutes of conversation, to step over the line from being a clean nosed good citizen to being a felon. Anyone could do it.” In this compelling story, the characters change, and some grow, through choice and consequence.

Lovers of literary fiction will appreciate the fullness of the characters, the topsy-turvy plot twists, and the thought-provoking themes.

KAREN MULVAHILL (May 27, 2016)

Isles of the Blind

Robert Rosenberg

Fomite Press

Softcover $17.95 (494pp)

978-1-942515-18-0

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Every moment of this novel becomes appealing for its thoughtful approaches to the complicated nature of fraternal love.

A pitied son rejects low expectations, leading to a deep family rift in Robert Rosenberg’s Isles of the Blind, a rich and lengthy meditation on bloodlines and loyalty, personal and national accountability, and absolution.

Avram’s chronically ill younger brother isn’t expected to live into adulthood. Family sacrifices afford him a blessed childhood on a Turkish island, though Yusuf grows to resent his family’s stunted expectations and is impatient for more. When his mother dies early, in a state of poverty that he is determined to personally subvert, the discord between father, brother, and son seems insurmountable.

While Avram builds a quiet, respectable life, Yusuf becomes notorious: as a rare Jewish Turkish billionaire; as a playboy and a questionable benefactor to his servant’s beautiful young daughter; and, most dangerously, as a public figure relentless in questioning the Turkish government’s standard line on the Armenian genocide. National leaders are not saddened when a tragedy claims his life, but when Avram returns to the island of their childhood to renovate his brother’s mansion, he is faced with his own considerable regrets.

The novel builds its setting and characters with quietude and grace, affording Avram the narrator’s place. He relates Yusuf’s story with love, but also with confusion and frustration. Yet as Avram repairs Yusuf’s home and delves into the historical questions that likely got him killed, he comes to understand his brother better: as a lonely man for whom no personal achievement was never quite enough.

In the movement of the novel, grand historical tragedies become the moral absolutes that help characters work around their more personal disappointments. Turkish life, with its sensuous movements and political quagmires, is imparted in a relatable and appealing way. But the tension between the brothers sits at the novel’s core. Avram’s moves toward recompense are emotionally compelling, and every moment of this novel becomes appealing for its thoughtful approaches to the complicated nature of fraternal love.

MICHELLE ANNE SCHINGLER (May 20, 2016)

My Radio Radio

Jessie van Eerden

West Virginia University Press

Softcover $16.99 (212pp)

978-1-943665-08-2

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Its pages are sharpened by contrasts—between the dull nature of a regimented religious existence, and the colorful needs of a young girl.

In a communal home in a quiet Indiana town, between four walls painted in wildly different colors, Omi Ruth works to come of age. Jessie van Eerden’s My Radio Radio details Omi’s intentional awakenings in piquant, empathetic prose.

Omi wakes one morning to find herself at the threshold of adulthood, her insides announcing her presence there in a way she cannot outrun. A bowl tips inside of her; she learns that her beloved older brother has been killed in a car crash; she encounters her first love, her “silent silver-white,” in an unlocked bedroom down the hall. In a matter of hours, she must grapple with being newly alone, freshly needed, and demonstrably no longer a child.

A new housemate, Tracie, who conceals more than one secret beneath her heavy sweaters, pushes Omi’s boundaries even more, forcing her to confront both her isolation and the nature of love, particularly considered within the sheltered religious environment of Solomon’s Porch. As Omi and Tracie’s bond deepens, and as the community’s secrets come more and more to light, Omi must come to terms with both the limitations imposed by her unique home life, and the probability that its odd movements began from a kind of love whose holiness she has not begun to fathom.

Van Eerden’s is a story of strained adolescence, made all the more complex by the demands of the small religious community at its center. Its pages are sharpened by contrasts—between the dull nature of a regimented religious existence, and the colorful needs of a young girl; between the ability to imagine great and magical bursts of beauty, and the stifled awareness of the unengaged world beyond one’s front door. Characters are drawn in all of their peculiarity, with such honesty that even those who seem outwardly small-minded are afforded depth. A reclusive preacher is not just a preacher; a boundary-pushing neighbor may be capable of kindness after all. Even Omi Ruth, who longs for wings, ends up finding that there are things on the ground worth her time.

My Radio Radio is a lovely, challenging, and fair-minded approach to the particular depths of those who populate small spiritual sects.

MICHELLE ANNE SCHINGLER (May 27, 2016)

No Certain Home

Marlene Lee

Holland House

Softcover $15.99 (340pp)

978-1-910688-00-7

Buy: Amazon

No Certain Home reveals an Agnes Smedley who, though she felt like an outcast for much of her life, became a true revolutionary for hire.

“A citizen of the world,” says writer, journalist, and spy extraordinaire Agnes Smedley: “I’m a freelance revolutionary.” Marlene Lee’s No Certain Home is a fictionalized account of Smedley’s life, one that may take some liberties with dialogue and character motivations but remains true to the timeline of Smedley’s adventurous and courageous life.

The novel begins in Shanghai in 1937, as Smedley interviews the Chinese general Zhu De. Zhu De’s story is alternated with chapters of Smedley’s biography, beginning with her childhood in Missouri. Born into poverty in the late nineteenth century, Agnes worked from a young age, took care of her three younger siblings, and refined her skills as a hunter, gatherer, and equestrienne. Fueled by her love of reading and a keen intelligence, she parlayed her autodidactic ways into a teaching job in remote New Mexico. Lee conveys Smedley’s sense of independence with a clipped narrative voice that resembles reportage and allows for little self-reflection or self-pity. Smedley is a bracing woman of action.

Smedley’s actions are motivated by injustice, inequality, revolution against the rich and powerful, sexuality, and a hunger for knowledge and understanding of the world around her. Lee gives context and grounding to Smedley’s many causes, including her participation in the fight for Indian revolutionaries to overthrow British rule, and her passionate devotion to the Communist Chinese party. Lee also covers Smedley’s inner struggle with sexuality, the idea of marriage, and her eventual acceptance, and physical enjoyment, of men as partners. This internal diversity is all well mapped and effectively conveyed.

No Certain Home reveals an Agnes Smedley who, though she felt like an outcast for much of her life, became a true revolutionary for hire. From pioneer to reporter to spy, and through many callings in between, Smedley had a veritable vagabond spirit, able to be contained by no man, ideology, or political system. Lee’s novelization of this historical figure is as breathtaking as was Smedley herself.

MONICA CARTER (May 27, 2016)

Remember My Beauties

Lynne Hugo

Switchgrass Books

Softcover $15.95 (194pp)

978-0-87580-736-2

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

This is a lyrical, down-to-earth snapshot of a pocket of flawed humanity.

Remember My Beauties, by Lynne Hugo, chronicles the hauntingly poetic crumbling of a horse-breeding family as a woman struggles to cope with buried secrets, rebellious children, and caring for the family’s beloved horses.

In the idyllic Kentucky pastures, an elderly horse breeder and his wife refuse anyone’s care but that of their hardworking daughter, Jewel. Jewel, however, is dealing with her own issues, including a drug-addicted daughter and her own slightly unstable mental health. Jewel attempts to care for everyone around her without losing herself in the meantime, but eventually she throws in the towel, and the family falls into disarray. That is, until her malcontent brother and scheming second husband step in. Before long, the bonds that connect each of these colorful characters are tested and strengthened.

Hugo paints her characters lovingly, with deep flaws and quirks that make them all the more real. When describing a fight between Jewel and her daughter, Jewel states that the daughter spews complaints as if “she were being paid by the word,” but Jewel retorts, “I’ve never charged for sarcasm, since it comes to me so naturally.” Shifting points of view can be disconcerting but are also used to strong effect: Jewel’s husband comes off as an oaf until his added perspective is shown to round him out. Not all the characterization is positive, as there are some dark secrets hanging in the family closet, including molestation, incest, and other trauma. Those flaws, however, help flesh out this family and make for an engaging read.

Remember My Beauties is a lyrical and down-to-earth snapshot of unsympathetic characters who, because they are so clearly defined and motivated, become captivating and heart-achingly beautiful. A pocket of flawed humanity bound by the love of innocent animals elevates this story that shines a light on the value of family, love, and the connections that keep everything on a steady trot.

JOHN M. MURRAY (May 17, 2016)

The End of Miracles

Monica Starkman

She Writes Press

Softcover $16.95 (390pp)

978-1-63152-054-9

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Best of all is Starkman’s portrait of Margo—a flawed yet admirably strong victim of circumstance and biology who refuses to be a victim anymore.

Monica Starkman’s novel The End of Miracles focuses on one woman’s longing to conceive—a primal, nurturing desire that somehow goes terribly wrong.

For Margo Kerber, the novel’s stoic and sensitive protagonist, the path to motherhood has been troubled from the start. Consultations with a fertility specialist leave Margo and her husband feeling like lab animals—studied, poked, and prodded—their sexual relations now “controlled by doctor, date, and a woman’s monthly rhythm.”

Margo endures these procedures because she is a hospital administrative professional and is well aware of how modern medicine can create miracles. Her doctor praises her for her diligence and her “painstakingly kept” cycle charts. Yet when the treatments continue to fail, Margo is advised to accept the fact that she may never naturally bear a child and to consider other options.

Margo’s paradoxical nature is integral to The End of Miracles. She alternates between calm efficiency and intense emotion, along with feelings of inadequacy that are made worse by the constant focus on her “barren” womb. She wakes from dreams of a tide of tiny infants rushing from her mouth, haunted by babies even in her sleep. Margo’s need for composure is soon tested, however, by an unexpectedly joyful pregnancy followed by a miscarriage.

Starkman’s measured plot builds effectively to this catastrophic event. Clinical details underscore the drama of Margo’s late-term miscarriage—her premature labor is long and painful, with just enough possibility for the baby’s survival to make the ultimate loss all the more heartbreaking. Afterward, when Margo’s body produces false pregnancy symptoms and cruelly tricks her again, it is clear that she’s been driven to a breaking point.

Margo’s collapse, unraveling, and gradual recovery bring The End of Miracles to a conclusion of forgiveness and hope. A psychiatrist, the author has a decided slant toward the power of psychotherapy, but her professional experience also adds technical depth and emotional breadth to the novel. And best of all is Starkman’s portrait of Margo—a flawed yet admirably strong victim of circumstance and biology who refuses to be a victim anymore.

MEG NOLA (May 27, 2016)

The Lost Civilization of Suolucidir

Susan Daitch

City Lights

Softcover $16.95 (332pp)

978-0-87286-700-0

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Daitch’s novel is Indiana Jones for the introspective crowd—a continual, thrilling, and harrowing search for historical treasures.

Beneath the sands of Iran lies a civilization lost millennia ago, rumored to have housed the lost tribes of Israel. In Susan Daitch’s The Lost Civilization of Suolucidir, generations of seekers journey into perilous spaces to validate the legend.

Discovery can be incidental, even for those trained in quests. So archaeologist Ariel Bokser finds, when almost-discarded papers yield a clue to the location of the mythical Suolucidir. Ariel makes his way to Iran during the final days of the Shah’s leadership, and his discovery seems fated indeed: he falls into the concealed kingdom, walking streets left untraveled for centuries. Or so he thinks.

A violent regime change forces him out of the country, bearing only a few decontextualized relics. At home, he works to piece together a picture of life in that lost land—and finds that he was not nearly the first to make the discovery.

Daitch’s pages take an intrepid trip back through generations of adventurers, all lost, in one way or another, to the sands above Suolucidir. A couple escaping the Nazis’ advances find it—in time with two fiends who want to destroy it for their own gain; they, too, are preceded by two journeyers who also don’t quite believe in the city until they see it. Again and again, the thrill of discovery is muffled by historical circumstance, and the lost city fades back into silence. Ariel, losing even what he smuggled out, must learn from those previous failures Suolucidir’s most enduring secret: some memories are best left undisturbed.

Found papers and cautious bits of correspondence are used to flesh out the mysteries of past expeditions so that even engaging this story becomes an academic exercise: truths must be sifted out from intentional fictions, and the distortions of time must be chipped away with sharp discernment. Characters become relics themselves to succeeding generations, so even Ariel’s documentation becomes part of the city’s alluring history.

Daitch’s novel is Indiana Jones for the introspective crowd—a continual, thrilling, and harrowing search for historical treasures that produces, time and again, the glittering notion that the present is more precious than relics of the past.

MICHELLE ANNE SCHINGLER (May 25, 2016)

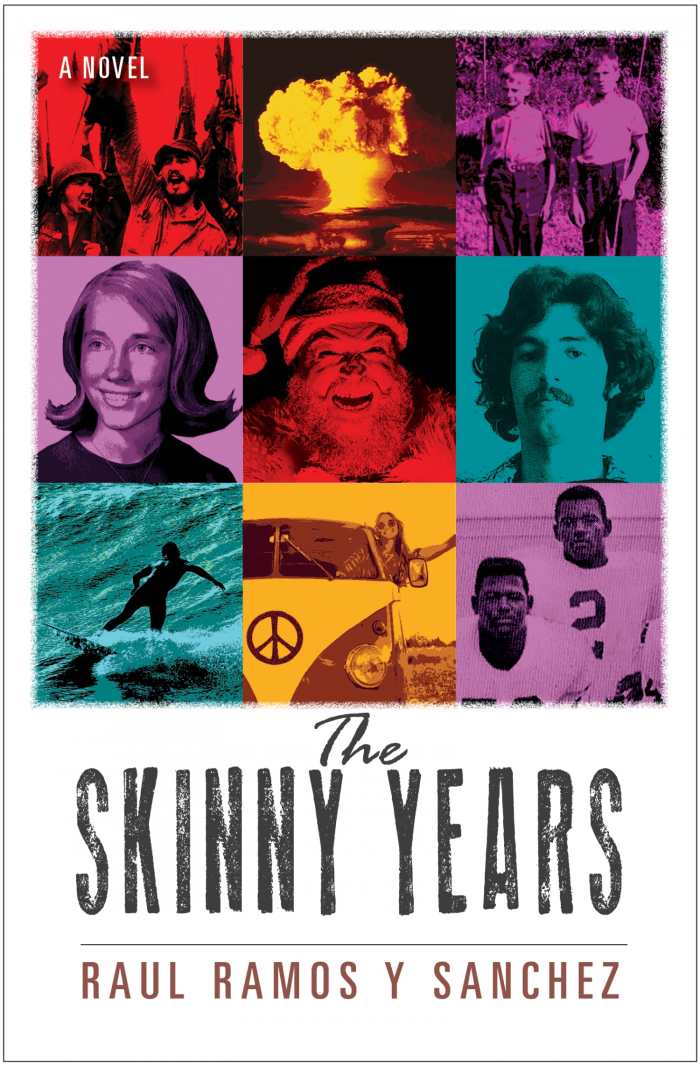

The Skinny Years

Raul Ramos Y Sanchez

Beck and Branch Publishers

Softcover $13.99 (246pp)

978-0-692-60841-8

A family flees from Castro’s Cuba, in this gritty, humorous novel about a young boy’s coming of age.

Raul Ramos Y Sanchez’s The Skinny Years is a complex, humorous, and utterly absorbing coming-of-age tale set in the 1960s. With themes of friendship, family loyalty, and economic hardships, the novel explores a decade in the life of eight-year-old Victor “Skinny” Delgado. The novel opens with Victor’s father, Juan Delgado, and his family living a life of luxury and success in Havana. As a professor of law at the University of Havana and a top supporter of the Batista regime, Mr. Delgado is proud of his anticommunist essays, but when Fidel Castro takes over, Batista and his defenders flee Cuba for their own protection.

Mr. and Mrs. Delgado, Skinny, his little sister Marta, and his maternal grandmother are left with little money when they arrive in Miami. Forced to live in a small house, with roaches as roommates, Mrs. Delgado takes a job as a hotel maid to support the family. Mr. Delgado refuses to work, convinced that Batista will regain power and the family’s former riches will be restored. With the constant negative undertow in his home, Skinny decides to spend most of his time out in the neighborhood.

When Loco, a local kid with red, bushy hair, saves the overweight Skinny from getting into a fight at the park, they become loyal friends. Loco is also Cuban and helps Skinny adapt to some of the cultural differences. Ramos infuses the novel with comical teaching moments, as when Loco takes Skinny trick-or-treating for the first time. Skinny informs Loco that he will not wear his mother’s scarf when they dress up as pirates, but Loco advises Skinny to “cut the macho act … this isn’t Cuba. Nobody here is going to think you’re a maricón for wearing a scarf on Halloween.”

Ramos has written a realistic, gritty, and witty coming-of-age story that focuses on not only Skinny’s growth, but the growth of all the characters. This well-written novel about the Cuban experience in 1960s Miami offers a much-needed perspective to that era of American history.

MONICA CARTER (May 27, 2016)

Hannah Hohman