Wings Press: With 'Latin@ Rising' Release, San Antonio Publisher Continues to Soar

An independent publisher with an appellation as uplifting as Wings Press just sings ascent. But looking over the catalog of the San Antonio-based house—a list that includes such literary luminaries as Lorna Dee Cervantes, Rosemary Catacolos, and Naomi Shihab Nye—one comes away with the impression that Wings Press was ever invested in spreading its multicultural message on a total grassroots level.

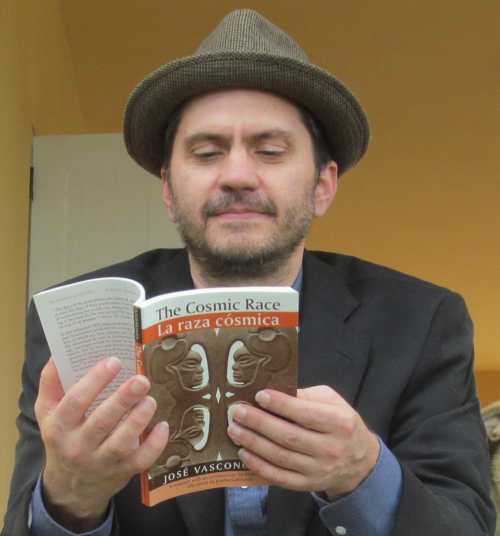

Bryce Milligan: 'The current political climate has only made me more determined.'

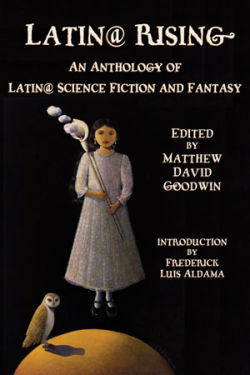

Matt Goodwin: 'There were no anthologies like this out there.'

Founded in 1975 by Joseph F. Lomax and Joanie Whitebird, Wings started out as a predominantly poetry-driven venture of very limited, often hand-sewn chapbooks. Twenty years later, poet/novelist/musician and self-described “follower of the muse” Bryce Milligan took over the house when he agreed to hand over a hundred bucks to Whitebird (who had become sole publisher after Lomax’s death in the late ’80s) and swore a spit-palms blood oath to keep the press going.

Under Milligan, Wings Press soared, garnered awards and nominations for books by writers such as Margorie Agosin, Carmen Tafolla, and Cecile Pineda. With the 2017 release of Latin@ Rising, Wings has published one of the first collections of Latino science fiction and fantasy.

“I’ve always been a fan of fantasy, more so than science fiction, though I’ve read a lot of SF too,” says Milligan, who kept up a correspondence with J. R. R. Tolkien until the author’s death in 1973 and counts Lord Dunsany, C.S. Lewis, and Frank Herbert among his literary influences.

‘No anthologies like this out there’

The decision to guide Wings toward this groundbreaking anthology is one Milligan had been heading toward for years.

Back in the 1990s, when he was running the Inter-American Book Fair at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio, Milligan discovered the work of Kathleen Alcalá and was blown away by her style. “I thought it was an interesting departure from magical realism and I tried to put together a panel of Latino SF/fantasy writers for the book fair. There were none—well, no Chicanos anyway. Most of the Chicano SF folks have ended up in film, it seems.”

Decades later, when Matt Goodwin, the editor of Latin@ Rising called him up with his idea for the anthology, Milligan jumped at the project. “It seemed a natural to me,” says Milligan.

“There were no anthologies like this out there,” explains Goodwin, noting that there already anthologies of speculative fiction for Latin American countries, of black speculative fiction and afrofuturism, as well as anthologies of Native American speculative fiction. “So, we needed it,” says Goodwin, who believes that an anthology such as Latin@ Rising brings attention to the individual authors while suggesting that there is indeed enough similarly themed speculative writing out there to merit a curated collection.

Goodwin’s personal work experience with undocumented immigrants led him to the realization that, for migrants, the system being battled was so extreme that only a writer such as Franz Kafka could honestly and accurately explore it.

“This brought me to begin exploring Latino/a science fiction and fantasy,” says Goodwin, who not only felt for the exploitive and bureaucratic nightmares experienced by Latino migrants were being underrepresented by the sci fi/fantasy world, but that the actual style of the Latino literature being published often lacked authenticity and wafted of marketing.

While in graduate school, Goodwin, who is currently an assistant professor of English at the University of Puerto Rico at Cayey, began to believe—as Milligan observed—that too many Latino writers were repeating the same kinds of stories. “I knew that there was more going on, more complexities going on, in the community. And eventually I found the handful of Latino writers who were doing science fiction. This became the start of my dissertation for my doctorate in comparative literature: The Fusion of Migration and Science Fiction in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and the United States.”

A ‘Mix Tape’ of Latino Styles

Latin@ Rising, an anthology informed by Goodwin’s academics but intended for the general reader as well as the student, can be seen as his aim at a corrective measure.

Goodwin likens the variation of styles in the collection of stories and poetry to songs on a “mix tape,” a description that becomes abundantly clear when reading the anthology.

In Kathleen Alcalá’s “The Road to Nyer,” a character’s curiosity about her genealogical truths takes the form of an excoriating time-slip tourism that reveals stark sacrifices linked to ethnic secrecy in old world Catalonia. In “Sin Embargo,” Guatemalan-born journalist/novelist Sabrina Vourvoulias offers rare insight into the verbal-coding endured by immigrants while highlighting atrocities of Guatemala’s so called “dirty wars.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Junot Diaz’s “Monstro” extends the metaphor of subjugation and unification to monolithic levels with a savvy scary story in which a flesh binding disease causes a new terror of cohesion to erupt in Haiti; and Alex Hernandez’s “Caridad,” deftly takes the hive mind trope so familiar to SF to new levels of class critique while illuminating the sacrifices young Latinas often make in order to support their families.

At points mirthful and at turns absolutely morose, the two dozen pieces collected in Latin@ Rising are all tinged with an otherworldly frisson of familiarity that perhaps only socially conscious speculative work can provide.

Most of the pieces—from the irony-infested comedy of Richie Narvaez’s “Room For Rent” to the Kathy Acker-like avant-garde heartbreak of Giannina Braschi’s 9/11 mediation “Death of a Businessman”—lack anything close to optimism. A few works however—such as a good-natured buddy comedy offered in Ana Castillo’s “Cowboy Medium” or the lunatic alternative space race history of visual artist ADAL’s “Coconauts in Space”—bring a refreshing and risible balance to a book linked by themes of unrest and austerity.

Goodwin finds heavy, socially aware, metaphor in his collection, pointing out specifically “Caridad,” a story in which a young woman gets an implant which allows her to telepathically connect to her extended family, extends the tropes of sci-fi toward issues of immigration. “It shows how science fiction themes can be used to express the experience of Latino/a migration to the US.”

Goodwin also greatly admires “Room for Rent,” a dark comedy which achieves this same Brechtian distance but through the eyes of a space alien. “What is interesting with the space alien is that because it is an abstract and nonhistorical figure, it can connect colonialism to present-day migrations. It’s a tricky connection to make but the space alien can make it happen,” says Goodwin.

Goodwin’s efforts in Latin@ Rising have effectively married activism with entertainment, and perhaps even altered the Latino literary landscape. “When I finished my degree, the topic of Latino science fiction was not widely discussed. I thought that an anthology would help to get the word out about those writers who were doing it and then encourage those writers who wanted to write science fiction and fantasy but were being held back by the industry. Ultimately, the field needed a push. And these days things are a bit different and Latino/a speculative fiction has become an important topic in Latino/a Studies.”

The initial print run for Latin@ Rising was 3,000, which when considering that Wings generally does 2,000 for fiction and 1,500 for poetry, speaks to the high hopes for the project.

Every Publication an Event

With titles such as Pam Uschuk’s Blood Flower and Geoff Rips’s The Calculus of Falling Bodies, every Wings publication is an event.

As a small publisher that has brought forth works by some of the more prominent names in Chicano and even world literature, Milligan acknowledges the staying power his press garners from titles which have gone into multiple printings. “Carmen Tafolla’s children’s book about Emma Tenayuca, That’s Not Fair, is one of the most important books I’ve done, and it is now in its seventh printing, each about 3,000. Steve Schneider’s Borderlines: Drawing Border Lives had a good run too—around 15,000 in hardback, 3,000 in paperback. But by far the most important and the best-selling title I’ve done is the definitive edition of John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me. The ebook alone is over 15,000 downloads a year. I’ve republished or published everything the man wrote.”

Sales aside, Milligan has a list of gratifying discoveries. “I love Cecile Pineda’s writing, and when I found out that her three books were out of print, I told her that I’d put them back in print and publish pretty much whatever she wrote. And here we are with a total of eight books. Same thing for Margaret Randall. We have the same politics and I am very proud to have published eleven poetry collections by her. Same for Carmen Tafolla, Rosemary Catacalos, Maria Espinosa, Alma Luz Villanueva. I would have published anything that Raul Salinas gave me, but he died after we got out one book and one CD.”

Noting that his aesthetics probably have more to do with the press than what happens to be popular at any given point, Milligan adds, “I had hoped to publish more by Lorna Dee Cervantes, but she’s gone off in a strange direction.”

Although Milligan has recently elected to slow Wings Press down he has no intention of stopping or handing over the reins to anyone just yet. For a few years production was up to twenty-four books a year. “That was a killing pace, but I thought the works in hand were worth the effort.”

“I’m not looking for anyone to take over the press,” says Milligan,” I’m not shutting it down by any means—just slowing it to a pace I can more easily manage.” Linking the success of his press to a stable of vital scriveners, Milligan says: “Also, several of my best authors are getting older and producing fewer books.”

For Milligan, who has always been as active politically as he is aesthetically driven, the atmosphere of the current Trump administration and the looming threat to the arts are further motivating factors pushing him to keep up the literary fight.

“The current political climate has only made me more determined that what I do is ‘necessary work,’” he says, adding, “politics and literature have always been a good fit for me.”

Roberto Ontiveros is an artist, critic, and fiction writer. Some of his short stories have appeared in the Threepenny Review, the Santa Monica Review, and Huizache. Some of his book reviews have been published in the Dallas Moring News, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the New Jersey Star-Ledger.

Roberto Ontiveros