“With ruthless honesty and wicked humor …”

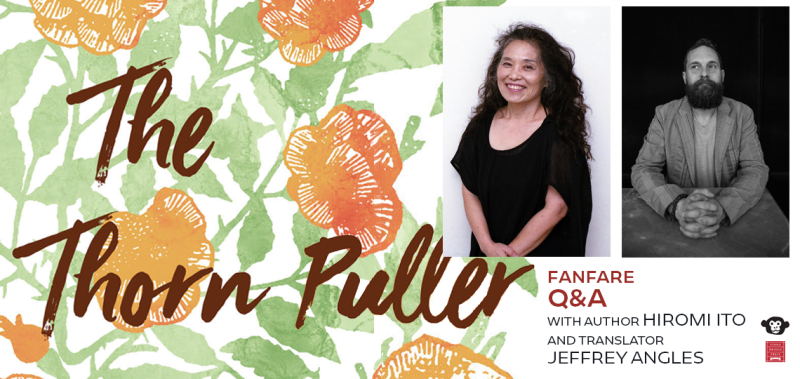

Reviewer Eileen Gonzalez Interviews Hiromi Ito and Jeffrey Angles, Author and Translator of The Thorn Puller

Women’s work … does a more offensive phrase exist? We think not, but the fact is, in the main, women end up doing far more of the daily tasks that keep families and societies functioning. Civilization wouldn’t exist if men were left to run the world.

Today’s featured novel offers a darkly humorous take on the life of a Californian woman overwhelmed and resentful of being a caregiver to her parents in Japan, while her husband’s health deteriorates, and her daughters make the all-too-common, relentless demands of their mother. Hiromi Ito’s The Thorn Puller earned a coveted starred review from Eileen Gonzalez in Foreword’s November/December issue, and we were thrilled to set up the following conversation between reviewer, author, and translator, Jeffrey Angles.

You are very frank and spare no details about any aspect of your life, even those aspects that other people might be embarrassed or uncomfortable talking about. Why is it so important to you to be so forthcoming?

This is one of the methods used in the practice of feminism—or at least this is what I seem to remember that the older, fellow proponents of feminism taught me during my teenage years. That was so long ago, however, that perhaps I’m dreaming it up or misremembering.

In any case, I was convinced that this was true when I started writing, and I found that writing this way helped me gain readers and reach people’s hearts. It also allowed me to plumb more deeply into the recesses of my own psychology. In other words, by writing about myself, I was able to connect to others and serve as a spokesperson relaying the voices of other people.

When I was younger, I wrote a great deal about child-reading and childbirth, and in fact, I had a column in which I would answer letters from readers about their personal troubles. That allowed me to listen to the individual worries of my readers. When responding, I had to really hear people’s concerns, and I took on the role of counselor or healer—albeit in a rather folksy, of-the-people fashion. That experience was also important to me.

Even in the midst of terrible or unhappy situations, you are able to find notes of humor, like your attempts to keep your daughter’s Tamagotchi alive while she’s at school. What role do you think humor plays in helping people cope with hard times?

Of course, humor and laughter allow people to relax and loosen up, thus orienting their lives in a better direction. By including these elements in poetry (or narratives), the author’s own perspective can become more self-reflective, even objective.

When I’m initially working on a rough draft of a piece, I always write in a very serious fashion, but as I go back and polish the work, I try to add some sort of humor. In doing so, I’m able to look in an increasingly objective way at the themes, events, and version of myself that appear in the text.

The god Jizo plays a sort of recurring role, connecting the different parts of the story. Was this planned, or did it develop naturally along the way due to Jizo’s importance to your family history and story?

There is a kind of Japanese storytelling known as sekkyō-bushi, which developed among commoners several centuries ago during Japan’s medieval period. Sekkyō-bushi combined elements of prose, poetry, and song in fairy tale-like stories about the suffering of ordinary people and the miraculous help that comes from deep prayer and fervent belief. Many of these stories include melodramatic, over-the-top plot twists that make them entertaining now, even centuries later.

From the very start, I wanted to write something that would be like a contemporary sekkyō-bushi, and I needed a figure like the Thorn-Pulling Jizō—a Buddhist figure still worshipped at a famous temple in Sugamo, located near the part of Tokyo where I grew up. For generations, the women in my family had gone there to worship and ask Jizō to remove the “thorns” of their suffering. I wanted Buddhism to be at the very heart of my story, so I decided on the Thorn-Pulling Jizō, which I knew so well.

I should clarify that Jizō is not really what you would call a “god” in English. Jizō is a bodhisattva—a figure who is putting the Buddhist principles into practice. Bodhisattvas listen to people’s troubles and walk with them. For bodhisattvas, helping others and bringing them to enlightenment is more important than achieving their own liberation. Their own liberation typically comes after they have helped others.

While The Thorn Puller is based on your experiences, a lot of it is fictional or fantastical. For instance, in one memorable scene, as you are talking with a poet friend, he “transforms” into Jizo before your eyes. How do you think this blending of fantasy and reality enhances the story?

Through the combination of fantasy and reality—or perhaps one could rephrase this as fiction and reality—one is able to delve more deeply into the unconscious mind, much like one does when dreaming at night.

While your story is in some ways extraordinary—not everyone has to worry about caring for relatives on two different continents—the core of it is something everybody will have to deal with sooner or later: aging and dealing with aging loved ones. What do you hope readers who may be struggling with these situations will take away from your experiences?

In gazing intently at one’s own struggles and turning them into a narrative, sometimes it is possible to find something of interest in all the small details and struggles. By doing so, I believe that will make it easier to continue living, facing all that life (and death) presents us. That’s what I’ve tried to achieve in this book—finding strength in suffering.

You reference and pay homage to a lot of other literary works, which you cite at the end of each chapter. How do you decide which works to borrow from and that will add something valuable to your story?

While writing each individual scene, certain “voices” from other literary works and people simply popped into my head. I didn’t purposefully set out to use these; however, I found that by quoting them, my own relatively straightforward language expanded, becoming all the richer and more complex.

Questions for Hiromi Ito’s English Translator, Jeffrey Angles

You mention in your note at the beginning that you encountered several challenges when translating this work, including the many verbs that can’t be translated precisely and the multitude of literary references that are unfamiliar to English-speaking audiences. Someone who reads The Thorn Puller in English is clearly going to enjoy the book in a different way than someone who reads it in Japanese. What do you think is the biggest thing that readers of the English translation will miss out on?

In Japanese, there is a far richer array of literary styles available than in English. Japanese is an old language with lots of variation, vocabulary, and possibilities, whereas English is a relatively new language with a comparatively small vocabulary. For instance, take Japanese folktales, classical prose, classical poetry, modern poetry, Buddhist sutras, sekkyō-bushi, and even email—all these genres have their own distinct literary style, and at different points in the book, Ito uses all of them. In fact, the playful combination of so many different styles was one of the factors that made Japanese readers enjoy this book so much.

Unfortunately, English tends to use the same words over and over in nearly all these genres, and even though I’ve tried to hint at the richness of the original through drawing readers’ attention to certain particularly intriguing words and turns of phrase, the translation did ultimately reconfigure the stylistic and lexical resources of Ito’s original. Individual style is notoriously difficult to capture in translation, so a polyvocal text like this which blends so many different kinds of styles, really makes the translator work hard to find interesting, creative solutions.

Conversely, do you think there is something about the English version that illuminates the subject matter in a way that the Japanese original couldn’t?

When people talk about translations, there is a natural tendency to focus on aspects of the original that might be lost, but I firmly believe that sometimes things are also gained in the process of translation. We might argue that the translation isn’t as stylistically or lexically rich as the original, but the converse way of looking at this same issue is to note that the process of translation helped forge a strong, unified voice for the narrator. I found that the relatively direct medium of English allowed me to really highlight Ito’s rich humor and wit—some of the elements that make this text so wonderful.

Hiromi Ito

Jeffrey Angles (Translator)

Stone Bridge Press (Dec 13, 2022)

Softcover $18.95 (300pp)

978-1-73762-530-8

In Hiromi Ito’s novel The Thorn Puller, a woman cares for her aging relatives across two continents while trying to maintain a life of her own.

In Japan, Ito’s parents rely on her to provide them care as their health fails. Meanwhile, back in California, her relationship with her husband faces pressures, including his own health problems. There is little humor in her struggles, but she manages to find some anyway, plucking wry observations from even the most tragic circumstances. All the while, she draws strength from family stories, folk tales, and religious rituals. She especially relies on Lord Jizo, a deity with the power to take away pain.

With ruthless honesty and wicked humor, Ito exposes the frustration and inconvenience of being a caregiver, juxtaposing it with the sorrow of watching a loved one deteriorate. She focuses as much on life’s beauty as on its ugliness, describing road trip landscapes and her parents’ incontinence with the same sharp eye.

In the midst of all, Ito has her own personal crises, from health scares to the death of a pet. Yet her duty to her family is always foremost in her mind: if something happens to her, no one else will care for her daughters, her husband, or her parents. Despite resenting her many responsibilities—from accompanying her parents to endless doctors’ appointments to keeping her youngest daughter’s Tamagotchi alive—she fulfills them, often with only Jizo for support. Her observations on life, death, and the in-between make for a fearless look at what every adult in every country must face: growing older as their loved ones do too.

The Thorn Puller is a darkly humorous semiautobiographical novel in which a woman attempts to remain strong in the face of immense responsibilities and inevitable losses.

Eileen Gonzalez