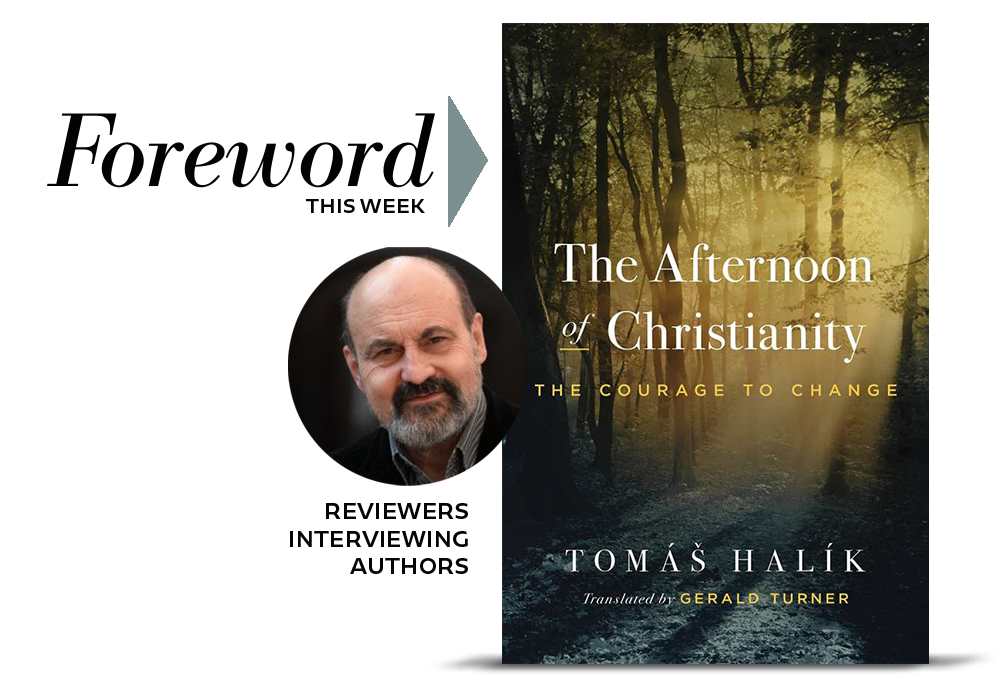

Words of Nourishment from Tomáš Halík, Author of The Afternoon of Christianity: The Courage to Change

“If the mystery of the Resurrection continues in history, then we should be prepared to seek Christ not among the dead, in the empty tomb of the past, but to discover today’s Galilee (“the Galilee of the Gentiles“), where we will find him surprisingly transfigured. He will once again walk through the closed doors of our fear, he will show himself by his wounds. I am convinced that this Galilee of today is the world of seekers beyond the visible boundaries of the Church.’’ —Tomáš Halík

We are in rarefied territory this week, stupendously blessed to spend a few minutes with Father Tomáš Halík, a hero from the days of fighting Soviet communism in Czechoslovakia in the 1980s, trusted ally of first Czech Republic President Vaclav Havel, and now as respected a Catholic scholar as you will find anywhere on Earth—leading the calls for Christians of all denominations to get along better, even as he hosts events with Jews and Muslims and befriends the Dalai Lama.

With courage in mind, let’s also note that in 2014, when Russia first invaded Ukraine’s Crimea, Father Tomáš castigated Vladimir Putin as a “war criminal” and hasn’t stopped that condemnation since. Such outspokenness surely had him placed on one of Putin’s dreaded lists but that’s the risk a lion takes: silence is the same as complicity.

The author of many books, essays, and spiritual treatises, the good father’s most recent release, The Afternoon of Christianity, earned a starred review from Jeremiah Rood in Foreword‘s March/April issue, which caused us to dream about a possible reviewer-author interview. Don’t wake us up.

The Afternoon of Christianity comes from a Catholic point of view, which seeks to make sense of how the world has changed and how Christianity has now reached a point where it has left traditional religion behind. The point here is not to chronicle the decline, but to discern in a faithful fashion what God is doing in this time. The book uncovers a faith that is in transition and changing in new and unexpected ways. I wonder what you found to be the most striking change to the church or Christianity itself?

In the history of Christianity, there have been repeated paradigm shifts. Today, not only modern Christianity (Christianity as one of the “worldviews”—”Weltanschaung”) is coming to an end, but the whole of modern civilization as it was formed after the Enlightenment. Modernity meant the fragmentation of the world. Also, “religion” became only one fragment of society and human life, and the Catholic Church became only one denomination. Christianity lost its catholicity, its universal openness; instead of Catholicity, which is the task of the Church, a narrow, ideological “Catholicism,” a caricature of Catholic openness, took its place. “Catholicism” as a counter-culture to modernity is a dead end in the history of Christianity. The attempt to come to terms with modernity at Vatican II (a turn from a strategy of defense to a strategy of dialogue) came too late—the modern age was already ending.

I see a clear call to renew Catholicity in Pope Francis’ efforts to restore synodality, especially in the encyclical Fratelli tutti. Catholicity still needs to be developed—the Church will be perfectly one, holy and Catholic only at the end of history, at the eschatological “omega point;” throughout history we are still on the journey (communio viatorum).

Christianity has lost the role of religion (religio) in the sense of integrative force and “common language.” Religio can also be understood as a re-legere, a new reading, a new hermeneutic, a new and deeper understanding and interpretation of both Scripture and Tradition, and a “sign of the times.”

I think a key point that people need to understand is the distinction you draw between faith and belief, with faith being a “certain attitude of life, an orientation, a way of being in the world and how we understand it, rather than mere ‘religious beliefs’ and opinions.” I think people in the west get caught up in this trap about belief often. Can you explain why that distinction matters?

Faith is a lifelong process of existential transformation: the transition from the “little ego,” from life on the surface, to a deeper centre; St. Paul expresses it in the words “I no longer live alone, Christ lives in me.”

Faith is the courage to enter the cloud of mystery and to live with the mystery. Belief is the effort to reflect faith intellectually and to articulate it with words, concepts, images, theories. This is important so that we can communicate about faith to others, so that we can share and celebrate faith with others. But at the same time, we must be free from our concepts and religious ideas and theories. St. Paul reminds us that we see everything here only as in a mirror, in a puzzle, in part.

There must always be room in our faith for mystery, further searching, new interpretations. The Bible and dogmas can be taken either literally or seriously. A literal, mechanical understanding means turning faith into idolatry, fundamentalism—into the opposite of faith.

If “belief” loses its relation to the deeper dimension of faith, to its existential-spiritual dimension, it degenerates into ideology, losing vitality and persuasiveness.

We don’t learn a lot about you in the pages of the text, beyond a little about your academic credentials. I wonder if you might discuss how your thinking about the future of the church and the faith informs the work you do. Can you tell us a bit more about yourself and your work today?

I told my story in detail in From the Underground Church to Freedom (Notre Dame University Press, 2019); people say the book reads like a thrilling detective story.

I was born in 1948, the year the Communists usurped the power to run Czechoslovakia. I was baptized Catholic but grew up in a secular Prague intellectual family with no religious upbringing. I converted at the age of eighteen under the influence of priests who had spent fifteen years in communist prison. During the persecution of the Church, I was secretly ordained in the private chapel of a bishop in East Germany.

Even my mother was not allowed to know that I was a priest; my civil profession was a psychotherapist for alcoholics and drug addicts. I worked as a “grey eminence” of the Archbishop of Prague, Cardinal Tomášek, who, being a very cautious bishop, became a symbol of spiritual resistance against the communist government. After the fall of communism in 1989, I began lecturing at the university, founded the Czech Christian Academy and the academic parish in Prague, and visited all the continents of our planet on lecture and study tours. In our parish I have baptized more than 3000 adults (the catechumenate lasts two years). My books have been translated into twenty-one languages.

I think we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention your critique of American Christianity, arguing that the United States is no longer the “city on a hill” that it once was. You argue, roughly, Christianity can now be seen in two competing ways in contemporary society, both through a deeper awareness of spiritual themes such as love of neighbor and a nascent tribalism that gives rise to Christian nationalism.

I find this idea of a tribally divided Christianity to be a compelling image or description for our time because it helps me to understand the sense that there really are different Christianities at work. After reading your book, I found myself being hopeful, if a little daunted. I wonder if you also find this time to be a hopeful one or do you see it more likely that the evils of white nationalism, say, are winning?

An American Catholic priest said that Christianity became a philosophy in Greece, a civilization in Rome, a culture in medieval Europe, and a business in the United States. This is certainly an unfair assessment; American Christianity had and has many faces. While European Christianity suffered the trauma of the violence of the French Revolution, the English and American revolutions did not have their Jacobin era of terror. The American experience that the Catholic Church can live IN a pluralistic and democratic society contributed significantly to the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. However, when I first came to the United States, watching religious programs on television, I had the impression that they were a blasphemous caricature of the Church, that no one could take many tele-evangelists or EWTN seriously.

Later I understood that the USA is really a land of unlimited possibilities, that everything is possible there. Great theologians such as Teilhard de Chardin, Tillich, Niebuhr, Lonergan found their home in the USA, and inspiring thinkers such as John Caputo and Richard Kearney are active here today. However, I am frightened by the attempts of the extreme right to exploit religious rhetoric for a populist and nationalist political ideology that is in direct contradiction to the Gospel. These people will be held responsible if immoral monsters take over the government and cause a total loss of moral prestige for the US in the world.

I love the style of writing in the book, which I found to be both meaty from a theological point of view and yet easy to read and understand. For example, you write that traditional ecclesial Christianity no longer has a monopoly on divine virtues, ie, faith, hope, and love, because these gifts are freely given and unrestrictedly.

Brilliant!

You’ve changed the thrust of traditional ecclesiastical thought by giving it the, pardon the pun, grace to succeed. I love the use of virtues here, because it harkens back, for me at least, to Aristotle and his virtues. Forgive me if this is an impertinent question, but I do find there to be an intriguing tension in your ideas and in the Catholic church and its love of tradition. Do you find a tension there?

We must distinguish between tradition and traditionalism. Franz Rosenzwieg wrote that tradition is the living faith of the dead, while traditionalism is the dead faith of the living. Tradition is the living river of creative recontextualization and reinterpretation of the entrusted treasure. Traditionalism is a denial of tradition, it is a modern heresy: an attempt to take a particular form of church or theology out of context, to fix it. In doing so, we make an idol of it, we deprive it of life. If tradition is the blowing of the Holy Spirit in history, then traditionalism, trying to stop this flow, is a sin against the Holy Spirit.

We’ve talked a lot about the book and its themes, but I’m wondering if there are any areas you had hoped we would talk about. Is there anything you’d like to say about the book to help our readers better understand it or your work? The floor is yours.

In the last few years, we have experienced an accumulation of dangerous global crises: global warming, with its impact on the natural environment; coronavirus pandemic; the Russian genocide in Ukraine; the conflict in Gaza with its impact on the growth of antisemitism, etc. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is not just a local conflict somewhere on the periphery of our world but will have global economic, political, social, and moral consequences. If the West does not show sufficient solidarity with Ukraine and cannot help it to stop Russian aggression, it will mean a total collapse of confidence in the democratic world and an emboldening of all dictators and aggressors worldwide.

The consequence of this accumulation of crises is the deterioration of the spiritual and moral climate of our planet, the growth of fear and insecurity. The growing sense of disorientation and anxiety about the diversity and fluidity of our world is creating a desire for simple answers to complex questions. Populism, nationalism, political extremism, and religious fundamentalism are spreading. Psychopaths, with a total lack of moral conscience, are emerging in key places in world politics.

The crisis of the churches is kairos, challenge, opportunity. The time has come for the self-transcendence of Christianity. The Church must also abandon its fixation on its “little self,” its fixation on just its institutional form at a given moment in history, or on its institutional interests. The terms clericalism, fundamentalism, integralism, traditionalism, and triumphalism denote various manifestations of the Church’s self-centeredness, its fixation on what is superficial and external. To succumb to nostalgia for an idealized past, is to be stuck in a too narrow (and often narrow-minded) form of Christianity—a sign of immaturity.

What is the future of Christianity? If the mystery of the Incarnation continues in the history of Christianity, then we must be prepared for Christ to continue to enter creatively into the body of our history, into different cultures—and to enter there often with the same inconspicuousness and anonymity as he once did into the stable of Bethlehem. If the drama of the crucifixion continues in history, then we should learn to accept that many forms of Christianity die painfully, and that this dying includes dark hours of abandonment, even a “descent into hell.” If, in the midst of history’s changes, our faith is still to be a Christian faith, then the sign of its identity is kenosis, self-surrender, self-transcendence.

If the mystery of the Resurrection continues in history, then we should be prepared to seek Christ not among the dead, in the empty tomb of the past, but to discover today’s Galilee (“the Galilee of the Gentiles”), where we will find him surprisingly transfigured. He will once again walk through the closed doors of our fear, he will show himself by his wounds. I am convinced that this Galilee of today is the world of seekers beyond the visible boundaries of the Church.

If the Church was born out of the event of Pentecost, and this event continues in its history, then it should try to speak in a way that can be understood by people of different cultures and languages; it should be constantly learning to understand foreign cultures and different languages of faith; it should teach people to understand each other.

Many of our concepts, ideas, and expectations, many forms of our faith, many forms of church and theology must die—they were too small. Our faith must surmount the walls built by our fears and our lack of courage to venture out like Abraham along unknown paths into an unknown future. In our new journeys, we will probably meet those who have their own ideas about the direction and destination, ideas that are surprisingly unfamiliar to us, but even these encounters are a gift to us; we must learn to recognize them as our neighbors and make ourselves their neighbors.

Jeremiah Rood