Adulthood Means a Bigger Library; Why Not Continue Reading YA?

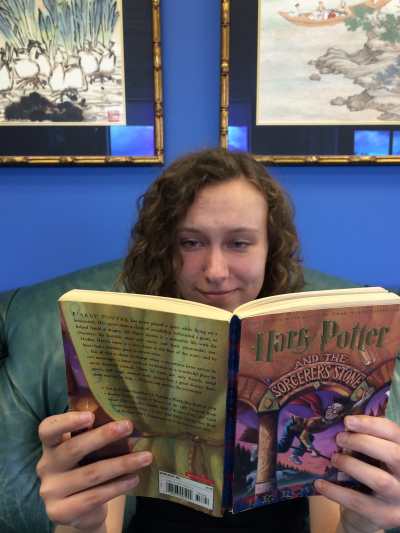

Aimee Jodoin: An adult unashamed of reading YA.

With the recent explosion in popularity of YA literature—beginning with Harry Potter in 1997 and growing exponentially with the widely read Twilight, The Hunger Games, Divergent, and The Fault in Our Stars—readers both young and old are filing into bookstores. In fact, more than half of YA novels are bought and read by adults, not teens. But with this increase in YA book sales comes backlash, such as that from Slate earlier in June, who said that adults “should feel embarrassed when what you’re reading was written for children.” Critics fear that teen-populated YA fiction is replacing “serious” literature among adult readers—and they’re beginning to judge adults readers of YA as somehow inferior. In truth, though, adults are simply realizing that YA has just as much to offer as fiction “meant for” adults.

When readers see young adult fiction, the majority will think of vampires, dystopian worlds, or naive romance. But what defines YA, really? In the world of adult fiction, there is high-brow literature, there are light reads, there’s dark crime fiction, there are romances, sci-fi, fantasy, and more. Genres are defined by tropes, writing styles, and sometimes page count—not by their target audience. Go the F–k to Sleep, for instance, is inarguably a picture book, but it’s definitely not for children. The format does not the audience make. YA fiction is no different.

The purpose of YA as a genre of fiction is to represent the life experiences of young adults, generally age thirteen to eighteen. A protagonist of this age is generally considered fundamental to the genre, as is the relative lack of adult themes, such as explicit sex and violence. Think a PG-13 movie: you’re allowed one F-bomb, no nudity (though kissing and sexual inference is fine), and minimal gore and drug use. That’s it. It happens that the assumed audience of YA is teens because the content of the books is appropriate for them (but just risqué enough to be exciting and make them feel grown up, and let’s face it, that’s what they really want), because they are members of the group of humans it aims to represent, and because, due to these factors, it’s marketed to them.

It makes sense that YA is read by teens. And it’s good. Having teenagers read books that feature characters similar in age and facing similar problems gets them more interested in books and allows them to reap the benefits of reading: namely better empathy skills. What doesn’t make sense is judging adults for enjoying the books as well. Just as an adult can watch a PG-13 film, an adult can read a novel documenting the experiences of a fifteen-year-old kid. We don’t refuse to read a book because the protagonist is of a different ethnicity or religious creed than us; discriminating based on age should bother us just the same. Adults need to be able to empathize with the emotions and experiences of teens, too.

Critics fear YA’s increase in adult readership because they believe it does not hold literary merit. This belief is hurtful both to teens and to the authors. It is also an overgeneralization. There are a variety of YA genres, just as there are adult genres, and each book (not just each genre) varies in its reading difficulty, writing style, and use of literary technique. Book-by-book, sure, but denouncing a whole genre’s permission to be eligible for serious critical reflection severely hurts the emotional and literary development of its readers, and it inhibits the evolution and betterment of a culture of which literature (no matter the genre) is an integral part. If you tell a reader that the genre they’re reading is inferior, they’re not going to pick up something you deem worthy—they’re going to stop reading. And that changes literary culture more than any genre does.

The beauty of being an adult is that we get to make choices about the books we read. So what if the main character is struggling through teenage issues, rather than adult ones? Just because it’s appropriate for a teen doesn’t mean it’s not appropriate for an adult. The two are not mutually exclusive. Entering into adulthood does not mean you must shut out books appropriate for a younger audience. It simply means that your scope of available books has widened. You can read adult fiction in addition to young adult fiction, unlike children and teens, who may not be ready yet to expand their repertoire of available literature. A new level of the library has opened up to you, but the previous one has not sealed off. There isn’t a “No Adults Allowed” sign. It remains open for your reading enjoyment.

Fear not the eye of the literary critic—your worldly understanding of the human experience (from a variety of ages and backgrounds) is widening while theirs is staying stagnant.

Aimee Jodoin is deputy editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow her on Twitter @aimeebeajo.

Aimee Jodoin