Eight Nights of Books: Light Up Hanukkah with These Great Titles

It has been argued that a devotion to the written word is The Thing that binds millennia of Jewish communities together. We’re not attempting to initiate a heady rabbinical debate, though; we’d rather just present you with eight great Jewish titles that we’ve read recently in honor of that undying light. Whether your interest is in Israeli life or the Shoah, in diaspora communities or the American Jewish Experience, we’ve got something for you on this list.

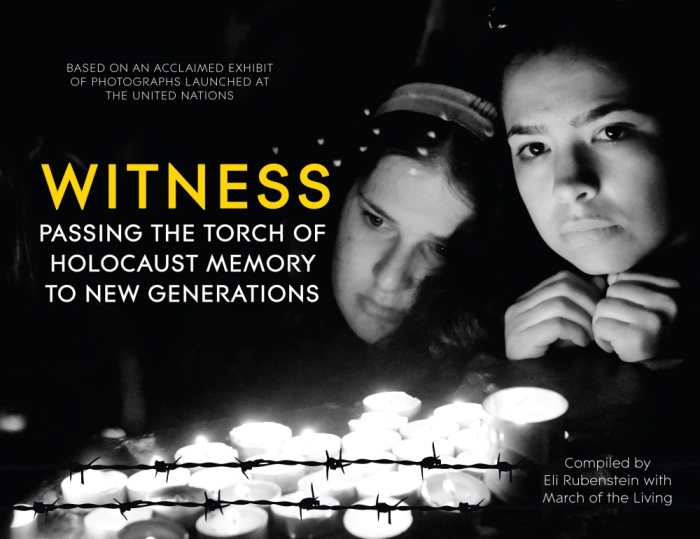

Witness

Passing the Torch of Holocaust Memory to New Generations

Eli Rubenstein, compiler

The March of the Living, compiler

Second Story Press

Hardcover $32.95 (136pp)

978-1-927583-66-1

Witness is a moving project, serving as both a memorial to those lost and a charge to not let such events repeat themselves.

Witness integrates photographs and survivor testimonies into an exploration of the Holocaust in its historical place. The project draws from the March of the Living—an international effort to familiarize later generations with the horrors of the Shoah—to explore the continued resonance of genocide in world culture.

The purpose of Witness, and of the March of the Living itself, is to ensure that the particulars of the Nazis’ genocidal efforts are never forgotten or repeated. As such, both incorporate the experiences and reactions of next generations across the religious spectrum. Witness includes a prefatory endorsement from Pope Francis, and photographs and testimonies from the March include interreligious and international reactions.

Into such reactions are woven stories of the Holocaust itself. The book begins by rooting anti-Semitism, first as a theological position, and later as one with racial overtones. First photographs are both shocking and familiar, including the liberated barracks at Buchenwald, from which skeletal survivors stare out at their liberators. Such photographs afford the readers opening opportunities to explore the cruelties visited upon those the Third Reich aimed to annihilate.

Just as compelling are stories from those perhaps less familiar: survivors hidden by the Righteous Among the Nations, survivors of the camps not as well known as Elie Wiesel. Photographs place these aging survivors amongst students who hope to learn from them, and center their testimonies in locales once horrific, and now left as memorials.

The project is meticulous about assigning credit to those who resisted Nazi tactics, both amongst those who formed resistance forces and citizens who protected those in danger. “I was brought up to believe that a person must be rescued when drowning,” writes Irena Sendler, an Oskar Schindler-esque figure, “regardless of religion and nationality.” Such imperatives echo as a never again, and stories of rescues—or national refusals to host refugees—reverberate with particular force.

Witness is a moving project, one which serves as both a memorial to those lost and a charge to not let such events repeat themselves. Poems and testimonials explore topics ranging from the nature of evil to forgiveness, resulting in tremendous emotional pull. This is an important and worthwhile collection, laden with moral imperatives that none should evade.

MICHELLE ANNE SCHINGLER (November 27, 2015)

Pascin

Joann Sfar

Edward Gauvin, translator

Uncivilized Books

Softcover $24.95 (200pp)

978-0-9846814-7-1

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

This is a whirlwind biography of Jules Pascin, “The Prince of Montparnasse,” a bohemian Jewish artist who lived and worked in France in the 1920s. Various vignettes from his life are portrayed, illuminating Pascin’s voracious sex life (starting at a very young age), his love of alcohol, and his diverse group of friends and companions, encompassing everything from fellow artists to gangsters. Though there are scenes of Pascin drawing and painting, Sfar chooses to focus on Pascin’s relationships, creating a more humanized portrait of the renowned artist. Pascin, and bohemian France of the ‘20s, is truly brought to life in Sfar’s skillful hands.

ALLYCE AMIDON (August 27, 2015)

The Psychiatrists of Phoenix Street

Michael Segal

Xlibris

Hardcover $40.31 (209pp)

978-1-4990-3403-5

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

These stories are both gorgeous in their array and, collectively, are a compelling picture of a national identity built on diversity and survival.

From Romanian-born psychiatrist Michael Segal comes The Psychiatrists of Phoenix Street, a sensitive and dynamic answer to patient case studies: a diverse collection of vignettes that bring together years of work in Israeli offices and hospitals. Drawing on the histories of patients ranging from the genuinely ill to the consistently hurting, Segal manages to paint the picture of a nation whose people struggle, for reasons personal and historical, toward health and wholeness.

The work gets off to a somewhat stilted start, with Segal trying, in a few pages, to describe his childhood in Bucharest and explain how he made his way toward medicine. The descriptions of his early home are lovely, though a brief meditation on why he turned toward science becomes a bit linguistically clinical. But talk of “the asymmetry of [his] cerebral hemispheres” gives way to Segal’s intriguing stories themselves, which are related with verve and sensitivity.

The first patient up is Amir, who seems to be suffering from a psychotic break. Segal approaches his case with curiosity and creativity, both hearing the patient and his loved ones out and working to explain Amir’s difficulties in inventive ways. This dance—between the scientific, the humane, and the investigatory—becomes characteristic of the work.

Amir is diagnosed with lead poisoning and sent home to his workshop with a healthy path forward. Not all of Segal’s patients prove so easy to cure. Some require medication, as with the immigrant from Russia whose harrying story of accidentally leaving his bipolar medication in his homeland winds toward a frantic, if happy, ending. Most, though, deal with the psychological aftereffects of Israel’s continuing story: The trauma of war. The pain of surviving the Holocaust when so many did not. The discomfort of being displaced.

Segal’s portraits are both gorgeous in their array and, collectively, are a compelling picture of a national identity built on diversity and survival. The stories examine the Yom Kippur War as experienced by many of Segal’s patients: the claustrophobia of being surrounded by hostile forces on a holy day, the fear and hurt associated with being caught, tortured, and surviving. The Holocaust, too, provides ground for survival narratives: patients who survived multiple camps, dependent on ingenuity and snippets of grace, articulate heart-breaking stories under the looming banner of “am I crazy?”

Most often, Segal’s answer to such questions is “no.” His patients wind their way back toward states of emotional well-being by naming what happened to them in their pasts, by relinquishing unfair survivor’s guilt and calling post-traumatic stress what it is.

Segal captures the beauty of Israeli landscapes, from Haifa to Jerusalem, with the same thoughtfulness he uses to explain his patients’ states. His book offers insights into a diverse nation, and readers may come away with a more nuanced view of Israeli psyches, and with greater sympathy toward a population that is frequently maligned in international media.

This brief and thoughtful book is a treat to read. The Psychiatrists of Phoenix Street adds new narrative complexities to questions of how national well-being and a people’s origins affect human stories at both personal and communal levels.

MICHELLE ANNE SCHINGLER (September 1, 2015)

The Sea Beach Line

Ben Nadler

Fig Tree Books

Softcover $15.95 (336pp)

978-1-941493-08-3

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

A brilliant and profound tale of one young man’s search for identity, and the stories we tell ourselves.

Brooklyn novelist Ben Nadler returns with a fabular coming-of-age novel that is both a love song to New York City and a Jewish son’s search for identity. The Sea Beach Line tracks Izzy Edel on his journey to find the hustler whose sketchbooks portray a mysterious history. An unhurried plot brilliantly captures Izzy’s transformation from a dropout to a young man forced to confront his own illusions.

When Izzy, a drifter and dreamer, receives news that his father, Alojzy, has disappeared, he’s determined not to accept it. With no way to verify the rumored death, he assumes the roles his father once held in hopes of discovering what happened. Much of the book centers on Izzy’s efforts to take over Alojzy’s book-selling business, his dealings with gangsters, his search for the faces his father repeatedly sketched, and his friendship with Rayna, a runaway. Memories of Alojzy intersperse with Izzy’s reflections: fragments of fiction he’s read, moments with his sister and soon-to-be brother-in-law, and scenes with fellow used-book sellers. The novel skillfully merges religion, a haunting painting of a woman, imagination, family, and perception, revealing its secrets one by one. Yet for all its intrigue, the story’s heart is a simpler, more profound account of delayed grief.

Izzy’s characterization is deft. Vulnerable, determined, an escapist, overly awed by his mythologized version of Alojzy, protective, an antihero whose heroics land him in trouble—he’s a complicated figure who fascinates. Rayna, one of the book’s pivotal figures, is presented as an ethereal woman who doesn’t stand out to the same degree, though the stories she tells convey necessary wisdom. Other noteworthy, minor characters include a strongman turned right-hand man to a don, a rabbi, and an opportunistic artist whose Coney Island museum serves as the site for several of Izzy’s reckonings.

The Sea Beach Line explores themes of self-reliance, solitude, loyalty, and the stories people weave to diffuse pain. With its colorful immersion into the mind of an unstable narrator, the work speaks to the powerful tide of memory.

KAREN RIGBY (November 27, 2015)

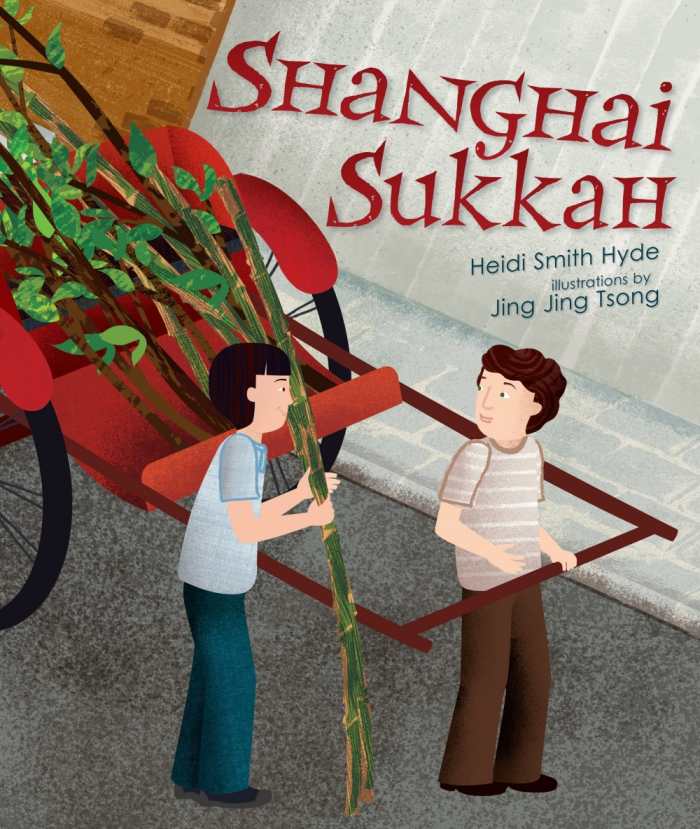

Shanghai Sukkah

Heidi Smith Hyde

Jing Jing Tsong, illustrator

Kar-Ben Publishing

Hardcover $17.99 (32pp)

978-1-4677-3474-5

Two boys—one Chinese, one Jewish immigrant whose family escaped Germany before WWII—team up to make the Chinese Moon Festival and the Jewish harvest holiday special for Marcus’s first Sukkot in Shanghai. Cultural heritage information is woven seamlessly into the narrative as the friends play marbles, build a sukkah from bamboo, and march with a paper dragon and lanterns in a parade. The illustrations depict Shanghai and the Jewish community in their historical contexts, but the friendship, and a timeless theme, take center stage. Ages five and up.

AIMEE JODOIN (August 27, 2015)

The Jewish Dog

Asher Kravitz

Michal Kessler, translator

Penlight Publications

Hardcover $19.95 (239pp)

978-0-9838685-3-8

Kravitz’s canine narrator describes the events around him without understanding their full impact, offering a new perspective on the Holocaust.

With The Jewish Dog, Asher Kravitz succeeds in the difficult task of finding a new approach to a Holocaust story by telling the tale through the first-person perspective of a family pet. Kravitz treats the material with the appropriate respect while using the dog’s changes in ownership as a clever way to flesh out history and provide an additional perspective.

The story opens with the dog, Caleb, introducing himself and explaining his circumstances, as one of several puppies born in the household of a Jewish family in 1935 Germany. Kravitz drops in hints about what’s on the horizon, whether through Hitler’s voice on the radio or another dog owner bragging about his pet’s pure breeding,

Because of the real-life Nazi decree that banned Jews from owning dogs, the family has to give up Caleb, handing him over to a German with a fondness for the animal. Caleb eventually passes through several owners, who range from kind to cruel, including some involved in the worst crimes of the Nazi era. At various points in his journey, the dog is on the run with a pack of strays, being molded into a prison guard by Nazi trainers, or taking part in a prisoner uprising. At times, Caleb, whose name changes throughout his ordeal, even takes part in atrocities, following the orders of new masters. In doing so, he offers a window into the soldiers or citizens who committed similar crimes, without excusing their behavior. He is haunted by an incident when he was a puppy, when he stood by while a fellow dog hunted and killed a harmless kitten, and thinks about that experience whenever he fails to do right.

Kravitz has some fun with the dog’s food-driven motivation, and the humor does not undermine the story’s tragedy. Because Caleb’s circumstances change so often, the story maintains its suspense, as it’s never obvious which parts of history the dog will experience directly.

JEFF FLEISCHER (August 11, 2015)

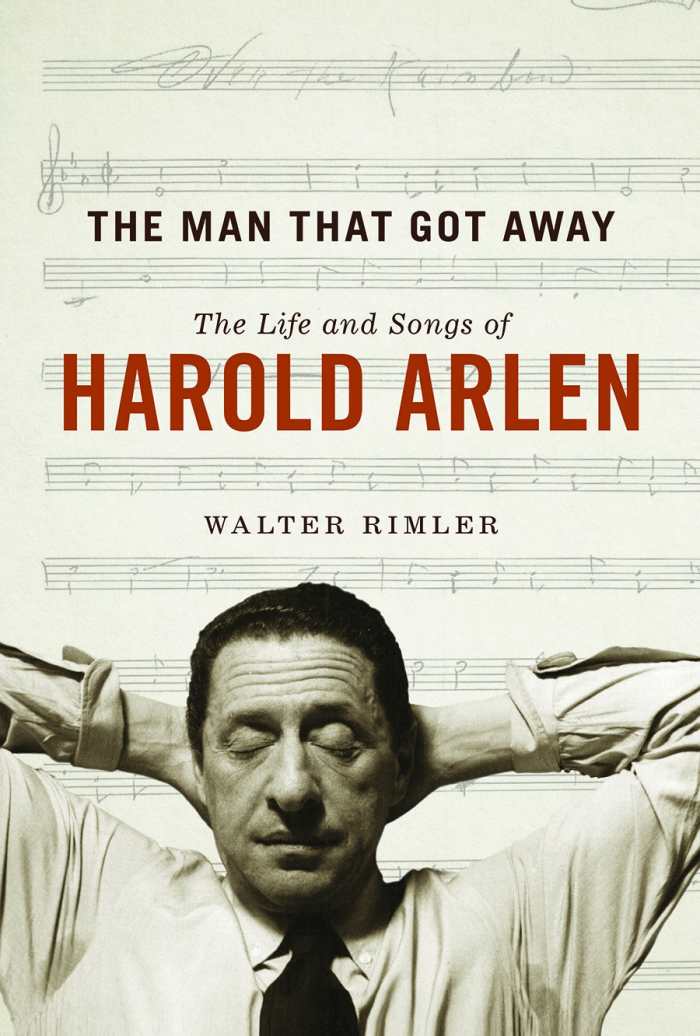

The Man That Got Away

The Life and Songs of Harold Arlen

Walter Rimler

University of Illinois Press

Hardcover $29.95 (248pp)

978-0-252-03946-1

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

This is a fascinating look at Harold Arlen’s beloved music, mixed with a good dose of name dropping, family drama, and nostalgia.

If you’re a member of the “greatest generation,” or even just a lover of the Great American Songbook, you know the work of Harold Arlen, even if the name is unfamiliar.

Among Arlen’s oeuvre are such memorable pieces as “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive,” “Blues in the Night,” “Get Happy,” “Come Rain or Come Shine,” and “Stormy Weather.” Add to that his work on feature films and Broadway shows, including his collaboration with Yip Harbug on The Wizard of Oz, and you’re talking about a member of the Mount Rushmore of popular music.

Walter Rimler—whose musical literary contributions include biographies on George Gershwin and Cole Porter—chronicles Arlen’s life from his humble (yet rebellious) musical beginnings as the son of an itinerant cantor through his early struggles on the way to his “overnight” and lasting success. At least it seems long lasting; according to the author, Arlen had relatively extended periods of inactivity which resulted in bouts of depression coupled with alcoholism. The situation was exacerbated, no doubt, by the songwriter’s troublesome home life, which gets a fairly equal treatment compared with the more glamorous stories of his entertainment connections.

Despite life’s intrusions—or perhaps inspired by them—Arlen continued to collaborate with the cream of the industry, including Harburg, the Gershwin brothers, Johnny Mercer, and Teddy Koehler, among others, churning out dozens of hits. There was a surprising amount of mutual support and admiration in what one would imagine to be a competitive livelihood.

The Man That Got Away is a fairly straightforward offering. Rimler at times indulges in a little too much “inside baseball,” discussing nuances in chords and composition structure that will be of interest only to students of music theory. Nevertheless, he provides an impressive overview of the challenges of working in such a demanding environment for Arlen and his contemporaries. The Man That Got Away is a fascinating look at Arlen’s beloved music, mixed with a good dose of name dropping, family drama, and nostalgia.

RON KAPLAN (November 27, 2015)

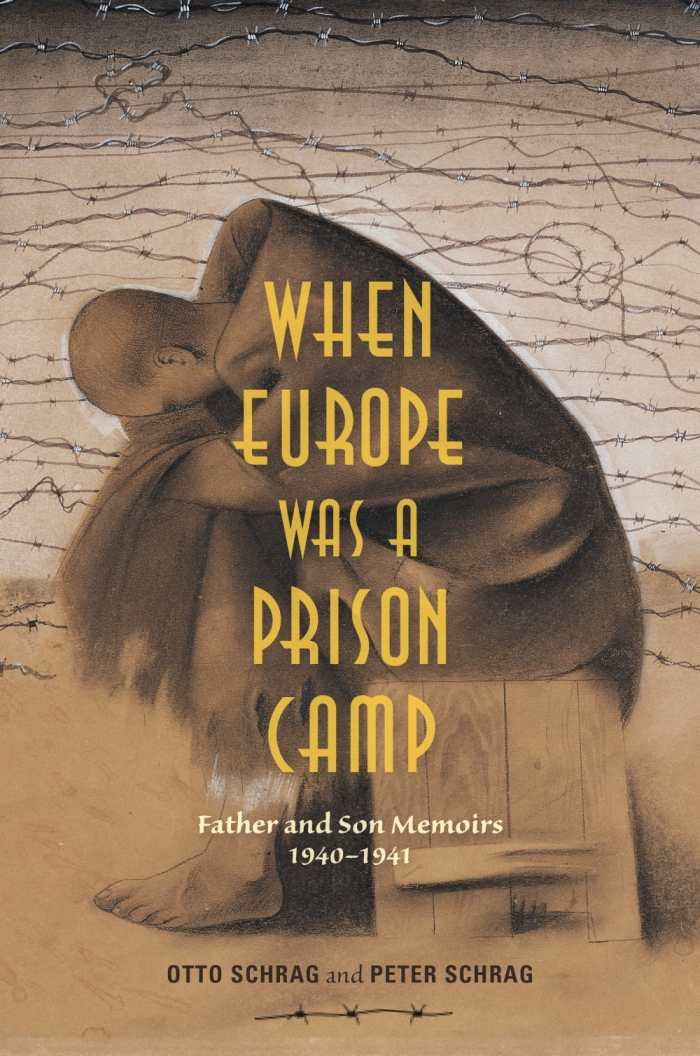

When Europe Was a Prison Camp

Father and Son Memoirs, 1940–1941

Otto Schrag

Peter Schrag

Indiana University Press

Hardcover $30.00 (328pp)

978-0-253-01769-7

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

This book takes a unique approach to a World War II memoir, combining not only the stories of a father and son, but both men’s years apart writing about the subject. When the Nazis invaded Belgium early in the war, Otto Schrag was arrested and put on a train west, while his wife and young son soon fled in the same direction. When Europe Was a Prison Camp includes the late Otto Schrag’s writing—in the form of a fictionalized memoir about his experiences in one prison camp after another—as well as Peter’s first-person recollections about his escape with his mother. The two perspectives really flesh out the events and the confusion of the time.

Otto’s detailed accounts tell of friends and strangers dealing with the uncertainty of where they’re being sent, whether they should escape, and what to do about disease outbreaks and other awful conditions. Meanwhile, Peter’s writing looks back, contrasting what he understood then as a child and what he has since learned about where they were, the risks his mother took, and how they found his father and emigrated. The dual perspectives are invaluable and create a fresh approach to an important story.

JEFF FLEISCHER (August 27, 2015)

Michelle Anne Schingler