More Novel Than Graphic: Authors and Illustrators Discuss the New Hybrid

When is a graphic novel not a graphic novel? Well, first of all, what is a graphic novel? Most people would consider a graphic novel to be, crudely put, a long comic book. But what about novels that contain comic-panel-like illustrations? They aren’t straight comics, not with the huge chunks of text they contain. And they certainly aren’t for young beginner readers, not with topics like drinking, drugs, school shootings, and the sinking of the Lusitania. They are, quite literally, graphic novels—novels that contain graphics. So can we call them graphic novels? To get to the root of this phenomenon, I talked with the authors of three such novels: Gail Sidonie Sobat, author of Jamie’s Got a Gun; Robert Gipe, author of Trampoline: An Illustrated Novel; and Frieda Wishinsky and Willow Dawson, author and illustrator, respectively, of Avis Dolphin.

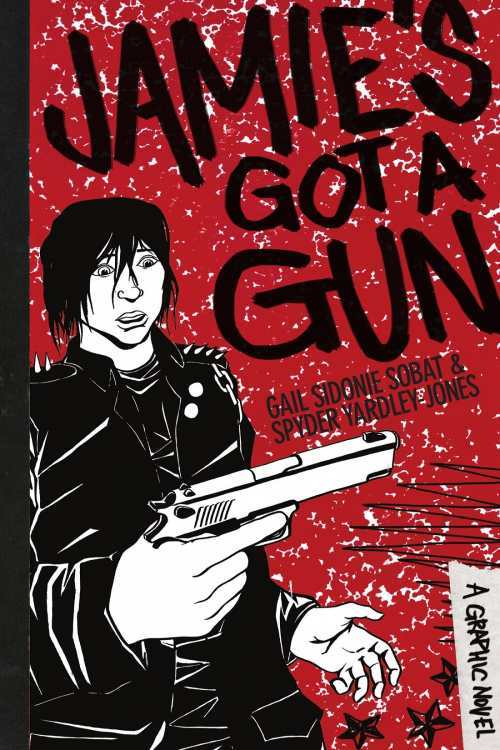

Gail Sidonie Sobat—Jamie’s Got a Gun

There are of course a lot of straight novels and a lot of straight comics, but this is probably the first 50/50 I’ve seen. How did you decide to go about writing the book this way?

Gail Sidonie Sobat

The story occurred to me as a dream with vivid images, so I knew, as a traditional writer, that this novel would be a departure in form for me, that it warranted a visual telling as well as a straight narrative telling. I knew there was only one artist who could draw what I envisioned, and that was Spyder Yardley-Jones. From the start, I saw the book as a hybrid of traditional novel and comic. I got the idea from Brian Selznick’s recent novels that use straight narration complemented by a series of images to tell a story: The Invention of Hugo Cabret and Wonderstruck.

Do you think there were things you were able to get across more clearly in illustrations instead of the text, and vice versa? And how did you decide which parts to do in comic form?

Yes, from the beginning, the parts of Jamie’s story that are most emotional or difficult for him to express in words are the scenes I wanted Spyder to draw. This is a boy who is dyslexic and pretty messed up. He, himself, is a comics artist who turns to his notebook to work out his struggles and his dreams. The novel is meant to be read as if you are reading Jamie’s notebook and looking at his artwork. Although, arguably, Jamie is quite good with words, he doesn’t believe that, but he does believe he’s a good artist.

Was your hope in doing it the way you did to make it more accessible and interesting for teenage and YA readers?

I definitely feel that school shootings are things we don’t talk about enough with young adults. We have drills at schools for lockdowns without ever talking about why someone would bring a gun to school and mow a bunch of human beings down. It’s so disturbing to me that there is no dialogue about this sociological trend, yet it terrifies all of us: parents, teachers, the general public, and most concerning, the poor kids who attend schools. We need to face that shadowy demon in ourselves, to read about it, think about it, talk about it. And that, for me, was the hope of Jamie’s Got a Gun: to start an important conversation with teens and adults and perhaps invite some collective soul-searching.

How would you define the term “graphic novel?”

I think the graphic novel is changing and in flux, and that is part of the beauty of its form. It’s not simply a comic series bound together as a book. I know that many consider Will Eisner’s A Contract with God to be the first graphic novel, and certainly I celebrate such books as Spiegelman’s Maus, but I think picture books without words (or with a very few words), are in fact graphic books. I think of David Weisner’s award-winning books like Tuesday or Chris Van Allsburg’s The Mysteries of Harris Burdick as works where the words are important, but the images are equally so. I guess that’s my definition. For me, a graphic novel is a form that cannot tell a story merely by words—the images are paramount to the narrative. Without them, the story arc would nosedive.

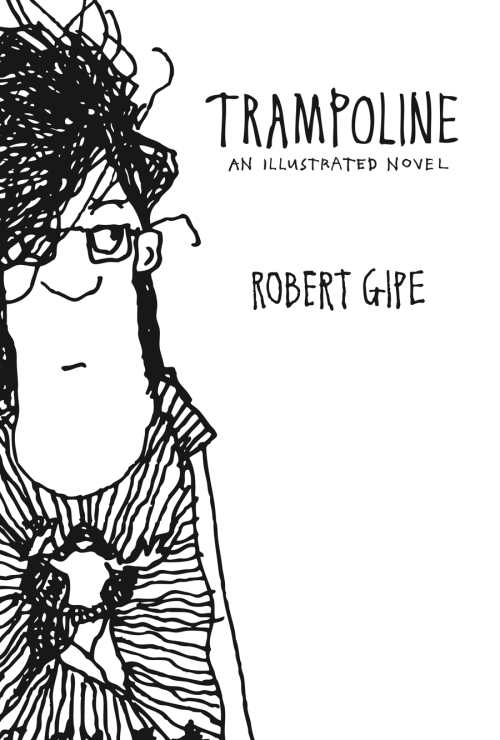

Robert Gipe—Trampoline

You don’t see a lot of illustrated novels that aren’t intended for young readers (though it’s a phenomenon I can totally get behind). How did you decide to go about writing the book this way?

Robert Gipe

When I finished the first draft of the novel—which was not illustrated—it did not immediately become the subject of a bidding war by the big New York houses as I had assumed it would. I backed up and said, well, if this isn’t going to be a big deal, what do I want it to be? I started producing the chapters as their own separate chapbooks with the illustrations. I like the design part of books, so it was fun making the covers and doing the drawings. I have always drawn. It’s much more of a compulsion with me than the writing. I grew up on Cracked and Mad magazine and love Chris Ware and Alison Bechdel and Daniel Clowes and Art Speigelman, so it was natural to start working this way.

Dawn is almost always drawn face out, addressing the reader, and her lines are clearly part of the story line. Or to put it another way, if you were reading this book out loud, you’d need to read Dawn’s illustrated lines, too.

Well, the book is rooted in all the oral history work we do at the community college where I work. I spend a fair amount of time listening to recordings of the speech of folks around here. I was interested in the reader experiencing the book as a story told by somebody live, something that is being spoken to them. I was interested in playing with the idea that yes, this book is a made object, a recording if you will, but that there really is a voice speaking within it. To have the reader see Dawn, see her speaking, and to see/hear her occasionally address the reader directly, seemed like a fun way to blur the line between spoken and written language.

Your illustrations are reminiscent of comic panels. You call this “an illustrated novel,” but what do you think of the term graphic novel? Do you think it should be expanded to include works like this?

I love words stringing out on a page. I kind of regretted giving the readers actual pictures of Dawn because I love picturing someone in a book in my mind and talking to another reader and hearing that they think the person looks totally different. I love the idea that readers make the book in their head. But I grew up running to the mailbox to get the newspaper to read Doonesbury. I can remember reading the news so I would understand better what was going on in that comic strip. I understand why we need categories like “graphic novel” and such—that bookstores and governments wouldn’t know how to organize themselves without them—but I think like a lot of people who make things, I am not that concerned with this book’s category or the names of categories generally.

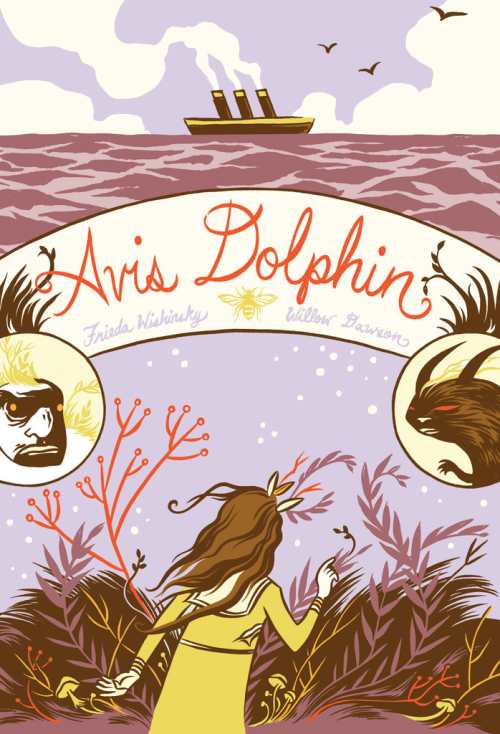

Frieda Wishinsky and Willow Dawson—Avis Dolphin

While illustrated books for young readers certainly aren’t a new phenomenon, I don’t think I’ve ever seen one quite like this: standard, unillustrated chapters interrupted occasionally by several pages of comics-style illustration. How did you decide to go about writing the book this way?

Frieda Wishinsky

Willow Dawson

Frieda: After reading the story of the real Avis Dolphin, we knew how much Professor Holbourn’s friendship and his stories of Foula helped Avis deal with her loneliness and fear on the voyage and beyond. We wanted to highlight that by weaving the “story within a story” in the text. We also wanted to parallel how Avis and Jill find the courage to cope with events beyond their control. Both girls are shipwrecked. Both face danger and death. Both are helped by the kindness of a friend.

Why illustrate just Foula? The descriptions of the ship make it sound like it could have been just as visually exciting.

Frieda: By illustrating Professor Holbourn’s “story within a story,” we hoped to contrast a magical/fairy tale with the real journey Avis took across the Atlantic. We hope readers will escape into the story along with Avis as she copes with the growing rumors of a German attack on the Lusitania. Stories help us all face tough times, and the professor’s friendship and his stories helped Avis through a terrifying experience. Years later, he even wrote a book for Avis (which was successfully published) after she complained that there were no adventure stories for girls.

Can you talk a little about the decision to go essentially wordless in the Foula pages?

Willow: I was thinking of the movie The Princess Bride where the grandfather’s narration overlaps, only slightly, with the boy’s imagination. I wanted Avis’s (and our young readers’) imagination to take over and essentially run away with/get lost in the plot. Even though I wrote a full script for the Foula story, it was obvious from the beginning that everything I needed to get across could be best achieved through the art. In comics, dialogue and narration that repeat what’s in the images should always be cut. Narrating the little fairytale wasn’t necessary as the panels already show us everything we need to know about what’s happening.

Do you think this book qualifies as a graphic novel? How would you categorize it?

Willow: There is a lot of confusion over the terms “comic” and “graphic novel” with many parents and teachers assuming that “graphic novel” is a higher art form. It’s not true—both are comics, just one refers to a longer format than the other. Unfortunately, this confusion is the reason we chose the term “graphic novel” to describe the story-within-a-story, even though technically, the length of the Foula story makes it more of a comic. We didn’t want the people at the gates (parents and librarians who don’t read comics/graphic novels and don’t understand the terminology but who have the power to hold books back from kids) to make the assumption the book, as a whole, was without substance. This, of course, could not be further from the truth.

Allyce Amidon is the associate editor at Foreword Reviews, where she blogs about comics and graphic novels. You can follow her on Twitter @allyce_amidon

Allyce Amidon