Get Your Wild On

Spring Nature Books

Sipping a latte, the glow of three digital screens casting a jaundiced glow on your face, never lose sight of the fact that you are feral at heart. Consider your ancestry. Not so many generations ago, your forebears roamed the African savanna and evolved over tens of thousands of years in the vicinity of saber-toothed cats, great bears, and other maneaters. But what’s become of you now, softie? Done any fight-or-flighting lately?

Here’s George Monbiot’s take on the subject: “We carry with us the psychological equipment, rich in instinct and emotion, required to navigate that world. But our survival in the modern economy requires the use of few of the mental and physical capacities we possess. Sometimes it feels like a small and shuffling life. Our humdrum, humiliating lives leave us, I believe, ecologically bored.”

Yes, we know the feeling, and as much as we love the following books, reading about nature is an unworthy substitute for a weeklong hike in the Rockies. Even so, high-quality nature writing and a wilderness experience can each bring a great deal of additional enjoyment to the other. Add to that the masterful writers—Thoreau, Whitman, Muir, Carson, Abbey, Matthiessen, Lopez, to name a few—filling out the roster of the nature genre, and it’s no wonder so many backpacks and saddlebags take on the extra weight of a book or two.

Downstream toward Home

A Book of Rivers

Oliver A. Houck

Louisiana State University Press

Hardcover $35.00 (256pp)

978-0-8071-5745-9

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

We live in the age of stand-up paddleboards and kayaks the color of molten lava. Rare now to see the graceful reach and pull of two paddlers guiding their canoe along a lazy stretch of an American river, drifting for a moment then simultaneously reaching again, a river dance as old as the hills.

Judging by Oliver Houck’s Downstream Toward Home, rivers have much to teach in the way of introspection, thoughtfulness, ecology, and writing skills. From Alaska to Florida, Arizona to Maine, Houck has been schooled by dozens of rivers in a paddling career spanning six decades—the thirty-two essays herein each recount his experiences on a different river.

In an early essay, in which he writes lamentably about not including his mother on a particular river trip, he tells this delightful anecdote about an old 35mm film clip of his mother and her father paddling together in Maine and coming across something in the water: “As the canoe approaches the object becomes a very large head with wide antlers, a moose, rolling one huge eye wildly back at this strange thing that was chasing it, coming right along side of it, and then this body with a hat on jumps and lands on its back. At her father’s urging, which means direction, my mother had mounted the moose and was holding onto its neck for dear life. The film shows them together like an old rodeo act, the moose swims madly for shore, my mother abandons ship, it stands a brief moment, shaking, and then bounds off into the brush.”

Appreciative of all his time on the water, Houck has worked on river conservation campaigns for the National Wildlife Federation, Environmental Defense Fund, Defenders of Wildlife, and National Academy of Sciences.

MATT SUTHERLAND (February 27, 2015)

Old Three Toes and Other Tales of Survival and Extinction

John Joseph Matthews

University of Oklahoma Press

Softcover $19.95 (200pp)

978-0-8061-5120-5

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

A bobcat needs a wristwatch like a cactus needs a calendar.

Yes, we have time, that peculiar human tendency to grid our existence into segments of seconds, minutes, hours, et cetera. But at what cost? What’s the tradeoff? We can be certain of one thing: living in expectation of the next thing on our schedule keeps us from being fully present in the here and now.

In each of the nine short fictional stories in Old Three Toes, John Joseph Mathews warps the passage of time to that of a desert rattlesnake—coiled next to a dry creek bed, motionless for however long it takes a warm-blooded critter to come within fang reach. He writes of the red deer’s ancient fear of eagles, somehow genetically encoded after untold thousands of generations of terror. And how a certain fawn named Royal rose up on his hind legs and struck at an attacking eagle with his front hooves, living to fight another day, albeit with a gray scar on his shoulder for the rest of his life.

The Osage author of several books and a hunter, Mathews died in 1979 at the age of eighty-four. His immense talent was centered around his ability to write about wilderness and wildlife through the eyes and ears and noses of animals. In an afterword, Susan Kalter explains, “Mathews’ deep empathy for other earth beings, his understanding of their individual consciousnesses and their intelligence both individual and collective, arose from his boyhood seclusion from the world of mankind, his early becoming embedded in the world of the birds and mammals with whom he engaged in the ‘earth struggle.’ His usually unconquerable urges to hunt were never to him a signal of superiority, but evidence unremitting of our commonality with all life.”

MATT SUTHERLAND (February 27, 2015)

A Terrible Beauty

The Wilderness of American Literature

Jonah Raskin

Regent Press

Softcover $15.95 (375pp)

978-1-58790-278-9

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Over the centuries, Americans have held conflicted feelings toward North America’s vast, treacherous, majestic wilderness, headed up by the cocksure, heavily-armed desire to subjugate—level the forests, eradicate the indigenous population, hunt the wildlife down to near or complete extinction. Ironically, this attitude was often accompanied by a sense of admiration— pride, even—of the continent’s natural beauty. Even so, the tame and the wild, the idea that a civilized Christian United States might comfortably coexist with great pockets of wilderness was not something most early Americans could wrap their brains around. That is, until the likes of Thoreau, Melville, and Whitman started exploring the American psyche.

In A Terrible Beauty, Jonah Ruskin performs the hugely important authorial service of providing readers with a discerning, erudite look at “the terrible beauty—the sacredness of the North American continent and the destruction of it—through the eyes of our poets, essayists, and novelists. American writers are nearly all wilderness writers. … In the pages of The Scarlet Letter, Moby Dick, Leaves of Grass, Walden, and elsewhere, we see ourselves and recognize ourselves as killers and as lovers, lovers who kill and killers who love.”

Ruskin analyzes more than thirty writers. His commentary, the contextual insight he brings, his word skills, all amount to a work of the highest pedigree. Intended as an introduction to American literature, A Terrible Beauty might better be seen as an explanation of American literature.

MATT SUTHERLAND (February 27, 2015)

Morning Light

Wildflowers, Night Skies, ad Other Ordinary Joys of Oregon Country Life

Barbara Drake

Oregon State University Press

Softcover $18.95 (200pp)

978-0-87071-760-4

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

As a genius nature writer, Henry David Thoreau made good use of his New England backyard and didn’t choose to explore the wild frontier that beckoned to the west in the mid- 1800s. He loved the way nature ceaselessly encroached on civilization: “There is something indescribably inspiriting and beautiful in the aspect of the forest skirting and occasionally jutting into the midst of new towns.”

Barbara Drake can relate. In nearly thirty years of living on a small farm in rural Oregon with a husband and border collies, she has trained her eye on the natural world sharing her beloved place. The lichens and mosses thriving on the forest floor of their large groves of white oak, for example, or the quick work a couple coyotes can make of sheep or chickens, the anxiety accompanying drilling a well for water, her satisfaction in recognizing stars and constellations in a brilliant night sky—this is the stuff of Drake’s life. Her many years teaching university-level English brings a sprinkling of Tennyson, Leopold, Eliot, and others, lending a commiserative voice to her warm, restrained, marvelously grown up way with words.

MATT SUTHERLAND (February 27, 2015)

The Anthropocene

The Human Era and How It Shapes Our Planet

Christian Schwägerl

Synergetic Press

Hardcover $27.95 (248pp)

978-0-907791-54-6

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Woe is Earth. Drilled silly, dumped on, farmed out, fished out, and cloaked in a burka of carbon—who does the planet have to thank for this dire state of affairs? Only its most highly evolved species, of course.

But woe is for whiners. As an enterprising species, we owe the planet a sense of optimism, accompanied by some promising solutions.

Enter Christian Schwägerl’s The Anthropocene: The Human Era and How It Shapes Our Planet, in which he justifies use of the term “Anthropocene” to designate a new human geological era based on the changes we’ve caused and our vital role as planetary stewards. Schwägerl and others (Nobel Prize winner Paul Crutzen, for instance) are championing the relationship between humans and nature as a revolutionary science-driven force. “By being geological,” he writes, “the Anthropocene opens a doorway between supposedly dead matter and living matter. It tells us that humanity and the technosphere it has produced are now participating in the largest and most long-term of planetary cycles, with conscious thought thrown in!”

Some of those areas where humans might positively integrate into the workings of the planet include cultivated life forms, human-induced biodiversity where needed, and smarter, more sustainable city planning.

MATT SUTHERLAND (February 27, 2015)

The Jane Effect

Celebrating Jane Goodall

Dale Peterson, editor

Marc Bekoff, editor

Trinity University Press

Softcover $18.95 (272pp)

978-1-59534-253-9

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

If Tarzan and Jane Goodall met for a drink at an eco resort in Ghana, would he have the good sense to shower first, and then thank her for putting Africa, conservation issues, and humane animal research on the map for hundreds of millions of people? Would she have the good humor to needle him about his king-of-the-jungle schtick?

The Jane Effect does Goodall the service of skipping the dry recitation of her career exploits and, instead, offering heartfelt, two-page testimonials from one hundred of her friends, colleagues, and students. They paint her as an impossibly kind, generous, intelligent human being and a scientist of the highest order.

Divided into eight sections—Jane as Friend, Jane as Colleague, Partner, Professor, Naturalist, Exemplar, Visionary, and Inspiration—the common thread between all the essays is Jane as life changer.

Most gratifying is to imagine eighty-year-old Jane, misty eyed, reading this ultimate tribute herself.

MATT SUTHERLAND (February 27, 2015)

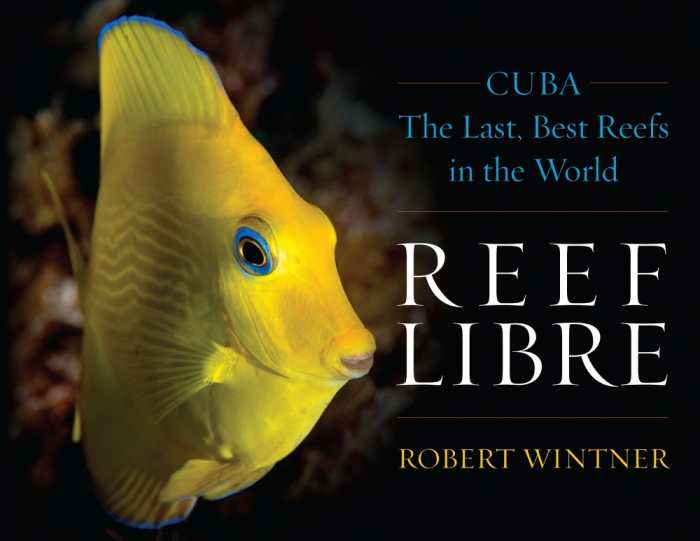

Reef Libre

Cuba—The Last, Best Reefs in the World

Robert Winter

Rowman and Littlefield

Hardcover $45.00 (280pp)

978-1-63076-073-1

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

SCUBA Cuba is fun to say, but the two words are also oxymoronic—a communist-minded acronym might better be: Smoking Cigars Underwater Begets Anarchy.

In any case, Cuba’s political and economic struggles have had one remarkable environmental consequence: her coral reefs are pristine.

In Reef Libre, Robert Winter details his amusing travels around Cuba, above and below the Caribbean waters. He gamefully discusses reef issues the world over, and makes recommendations for Cuba’s own reef management strategy—noting repeatedly that Cuba’s efforts to protect its reefs are far superior to Hawaii’s.

With two hundred photographs, Reef Libre is a stunning work of photojournalism. Winter is on the noblest of missions and sea life everywhere owe him an aquarium-sized cuba libre.

MATT SUTHERLAND (February 27, 2015)

Times Beach

John Shoptaw

University of Notre Dame Press

Softcover $24.00 (144pp)

978-0-268-01785-9

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

To poetize birchbark, floodwaters, crawfish chimneys, the Great Comet of 1811. To write knowingly about trapping swamp rabbits in the hollowed trunks of gum tupelo and the whistling sound of an earthquake in water:

Not unlike the mournful hissing scream a rabbit would make when pulled out by

its hind legs from a gum. At 15¢ a piece—with four good-luck

feet and a couple of stews—it would make, that year’s next morning, a pretty fair deal.

To poetize the Great Squirrel Migration of 1811, when, inexplicably, tens of thousands of the critters left their treesome ways and scurried south from the upper Midwest, running headlong into the unforgiving Ohio River:

Tail aquiver, we poured downtrunk and flooded the forest floor. An ordeal,

to be sure, but also an oddly

moving experience—deer, even bear, fled our fuzzy determination. Navigating by stars

or by each other, it was better together. Needy, distrustful, we were what we could never

rightly recollect. The river changed us unrecognizably, though we go on like nothing happened.

The uncanny combination of experience and skills is what places John Shoptaw at the very summit of nature poets. He anchors his personal experiences in the Bootheel of southeast Missouri as touchstones while he floats the Mississippi watershed through time. An amazing feat.

MATT SUTHERLAND (February 27, 2015)

Matt Sutherland