Large Lives, Larger Lessons

Biographies from March/April 2017

At heart, history is the story of individual lives. This collection of biographies bring new voices to life, probing the history of families, governments, social organizations, careers, and even individuals’ own bodies. Each engaging story reveals the legacy of greater social histories and what those legacies have born in the present. Stretching from the mid-nineteenth century through the twentieth, every selection shows that, for someone, the public sphere is always personal.

Inventing Loreta Velasquez

Confederate Soldier Impersonator, Media Celebrity, and Con Artist

William C. Davis

Southern Illinois University Press

Hardcover $39.95 (376pp)

978-0-8093-3522-0

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Loreta Velazquez, cross-dresser and alleged soldier for the Confederacy, fascinated people in her own time and birthed a legend that still generates interest today. Civil War scholar William C. Davis writes Inventing Loreta Velazquez: Confederate Soldier Impersonator, Media Celebrity, and Con Artist with urgency and flair, managing to make a cliffhanger out of history, in his quest to pin down the woman behind the legend. In his investigation, Davis discovers a story of media savvy, celebrity, and spin that could be ripped from today’s headlines.

Throughout Loreta’s life, the two dominant features were “her quest for respectability and a near obsession with attention and celebrity.” She wanted to be a writer, but other than press releases and a best-selling memoir, The Woman in Battle, she seems to have settled for being written about. In her own time, she went viral; stories about her crossed war lines to appear in newspapers from coast to coast in just days. She herself traveled almost as much, changing names and identities like clothing and living in almost every region of the country before her death. Little is known about her beyond the documents she produced, documents that conveniently legitimated her celebrity and furthered her schemes. And a schemer she was, manipulating the national media and constantly reinventing herself to establish social connections and generate income on little more than her story of the hour. Loreta seized history in her own time, but, in the process, she buried the woman behind that notoriety. Her aliases took on lives of their own and, in many ways, never really left the public imagination, while Loreta died in anonymous penury. Davis’s thorough, surprising research exhumes the historical Velasquez, bringing to life a troubled, determined person who knew how to manipulate and titillate better than the best.

LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (March 2, 2017)

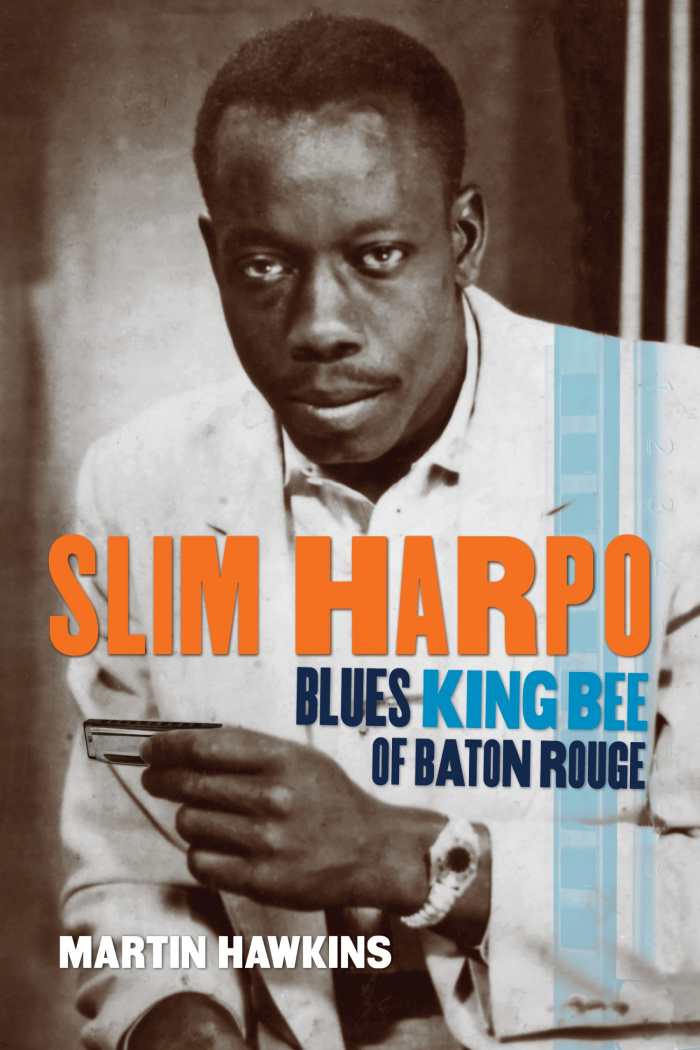

Slim Harpo

Blues King Bee of Baton Rouge

Martin Hawkins

LSU Press

Hardcover $35.00 (416pp)

978-0-8071-6453-2

Music writer Martin Hawkins searches for the origins of Baton Rouge blues and the man posthumously credited with establishing the sound and the town on the global music scene, in Slim Harpo: Blues King Bee of Baton Rouge. Harmonica player and bluesman James Moore, known by the handle Slim Harpo, died suddenly and mysteriously of heart complications at age forty-five, just as he was poised to secure his place in the international music scene. With Moore’s death, his early history and that of the Baton Rouge blues was lost, well before the man or his music became canon. Covers of Slim Harpo’s music by groups like the Rolling Stones helped preserve his legacy long after his demise, and Hawkins salvages as much as possible of what remains.

By all measures, Slim Harpo deserves a victory-lap account confirming his place as the grandfather of Baton Rouge blues. However, left with scant documentation and conflicting, often apocryphal, stories, Hawkins’s search for origins inevitably confronts questions of authenticity in both information about Moore and the idea of a distinct Baton Rouge blues sound. Smartly, Hawkins fills in what isn’t—and often can’t—be known with historical information about Slim Harpo’s time and place. The result is a surprisingly well-sketched picture of Moore, albeit in silhouette, as seen through the lives of his family members, band mates, and peers. Hawkins even manages to extrapolate Slim Harpo’s legacy by following the blues trail through the deaths of Harpo’s cohort and into the blues heritage revivals of the early 2000s. Given the amount of extant information about Moore, definitive conclusions are impossible, but Slim Harpo’s contribution to the swamp sound, his mark on US charts and British Invasion bands, and his enduring effect on the blues scene warrants every page of Hawkins’s tribute.

LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (March 2, 2017)

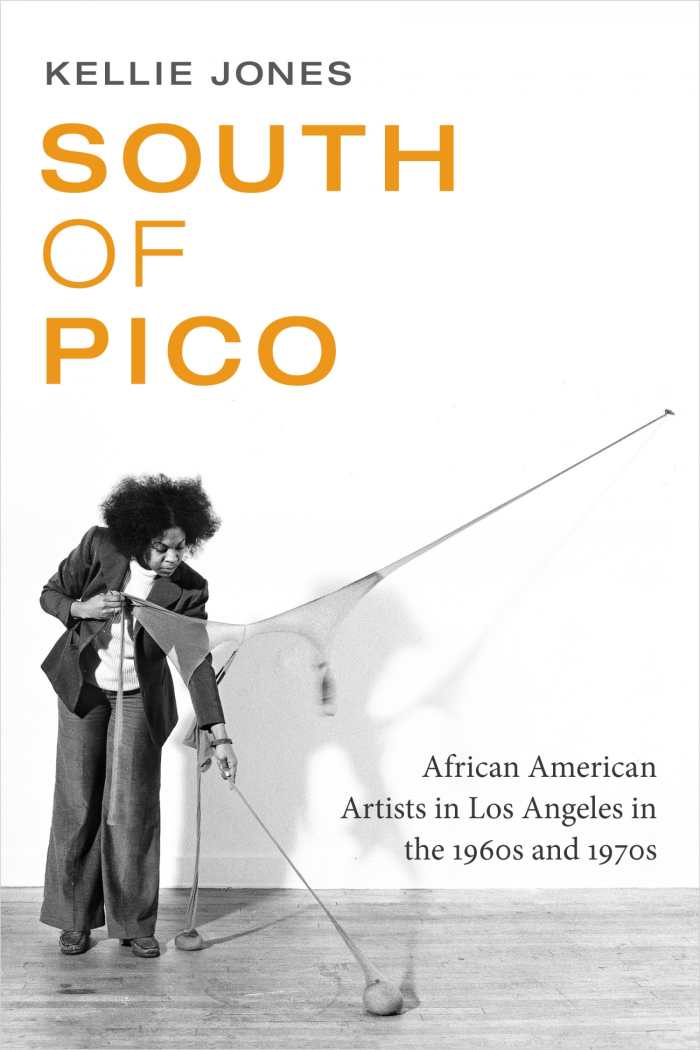

South of Pico

African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s

Kellie Jones

Duke University Press Books

Softcover $28.95 (416pp)

978-0-8223-6164-0

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

In South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, Kellie Jones, MacArthur Fellow, illuminates the historic forces and migrations that gave rise to the groundbreaking black artists and artistic communities of Los Angeles for almost three decades. Jones surveys two decades of artists (such as Charles White, Betye Saar, John Outterbridge, Senga Nengudi, and David Hammons, to name a few), their artistic output, and role in LA’s African American art scene and places them and their work in the larger artistic canon. In this work of deep-thinking scholarship, Jones locates Afro Modernism at the vanguard of a larger artistic zeitgeist while also grounding it firmly in the nexus of African American experience in social, geographical, and historical space.

Although African American artists were part of American culture, not other than it, the lack of institutional frameworks and infrastructure often ghettoized their work. The isolation of African American communities frequently meant that work by black artists was racialized and marginalized. Additionally, the complex lineage of slavery, mass migration, civic disenfranchisement, and segregation make Jones particularly interested in how the artists use place to “think about the future and to reconsider and reframe the past.” These artists’ response—in the use of black bodies, alternative materials and ways of making, and non-Western, non-white traditions—radically changed the art world. Their art created nexuses where memory, history, and community were contiguous with past, present, and future. Jones’s work establishes their historic space and does much to address the “struggle for the African American visual artist’s self-expression to be seen as intellectual history, their imaginings as agents of creative change or transformation.”

LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (March 2, 2017)

Ernst Kantorowicz

Robert E. Lerner

Princeton University Press

Hardcover $39.95 (424pp)

978-0-691-17282-8

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Ernst Kantorowicz, son of a wealthy German Jewish liqueur manufacturing family, aesthete, intellectual, confirmed bachelor, active bisexual, and groundbreaking medievalist, is a contentious figure, even within Robert E. Lerner’s Ernst Kantorowicz: A Life. Ambitious, self-confident, and privileged, Kantorowicz often presents like the definition of entitlement, but he twice put his coveted status on the line by publicly lecturing against the Nazis as a professor in Germany and again by refusing to sign the University of California’s loyalty oath during McCarthyism. Lerner’s chronological approach to Kantorowicz’s life illustrates his movement from the far right of German politics to the left of US politics while also developing the man behind the famous—and notoriously divergent—scholarly works Kaiser Friedrich der Zweite and The King’s Two Bodies.

In his youth, Kantorowicz was a German nationalist and part of the George Circle, young men devoted to poet prophet Stefan George, whose works inspired the Nazi Party. Even later in life, he gravitated toward elitism. Lerner delves into Kantorowicz’s ambiguities, assembling a picture of the man that includes both truncated explanations of his major works and vivid anecdotes of his life as excerpted from interviews and letters. Lerner doesn’t shy away from depicting or commenting on Kantorowicz’s many flaws; neither does Lerner manufacture excuses for him. Rather, Lerner’s accessible, conversational tone and deft use of quotation bring Kantorowicz to life, showing the man behind the scholar and the development of a brilliant mind over a lifetime. Throughout, Kantorowicz’s voice is sharply present. Lerner admits that, posthumously, motivations are impossible to discern, but his discernment is a gift in this unflinching treatment of Kantorowicz’s legacy.

LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (March 2, 2017)

The Turtle’s Beating Heart

One Family’s Story of Lenape Survival

Denise Low

Bison Books

Hardcover $24.95 (200pp)

978-0-8032-9493-6

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

The Turtle’s Beating Heart: One Family’s Story of Lenape Survival opens with a tribal elder’s explanation: “Delawares are like clouds….They never get together.” Thus, Denise Low tackles one of the longest diasporas of any US tribal nation, in her searching memoir about family, identity, and history. Written in three parts, Low speaks profoundly about difficult truths, teasing apart family stories and reweaving them into a larger narrative of historical trauma, where “the past is a presence, beyond language, memory, and culture.”

An accomplished poet, Low’s well-honed prose flows with lyric intensity. In Kansas, a place “where eternity has a real valence,” she searches for documentary evidence of her ancestors’ passage through history and for the timeless threads of culture—familial and tribal—that could offer an unbroken legacy. As she uncovers family history, the personal becomes devastatingly political as the outcomes of government and social policies emerge in the vastly different, often fractured identities her relatives have claimed in an ever-shifting, often hostile, world. She swiftly discovers tribal heritage is latent in her family’s culture, from consistent settlement patterns in riverine geography to glyphic writing discovered on family tombstones. Yet her family also exists in the penumbra of history, unregistered by the US government, off tribal rolls and reservations, and the ramifications are far-reaching and complex. Ultimately, Low resolves, “We are made up of many fractions of bloodlines, but family inheritance is not a single pattern so easily measured by mathematic abstractions….The heart beats extra blood to the dominant side. No fourth is equal [but] a human’s single heart is critical to existence, no matter which quarter holds it.”

LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (March 2, 2017)

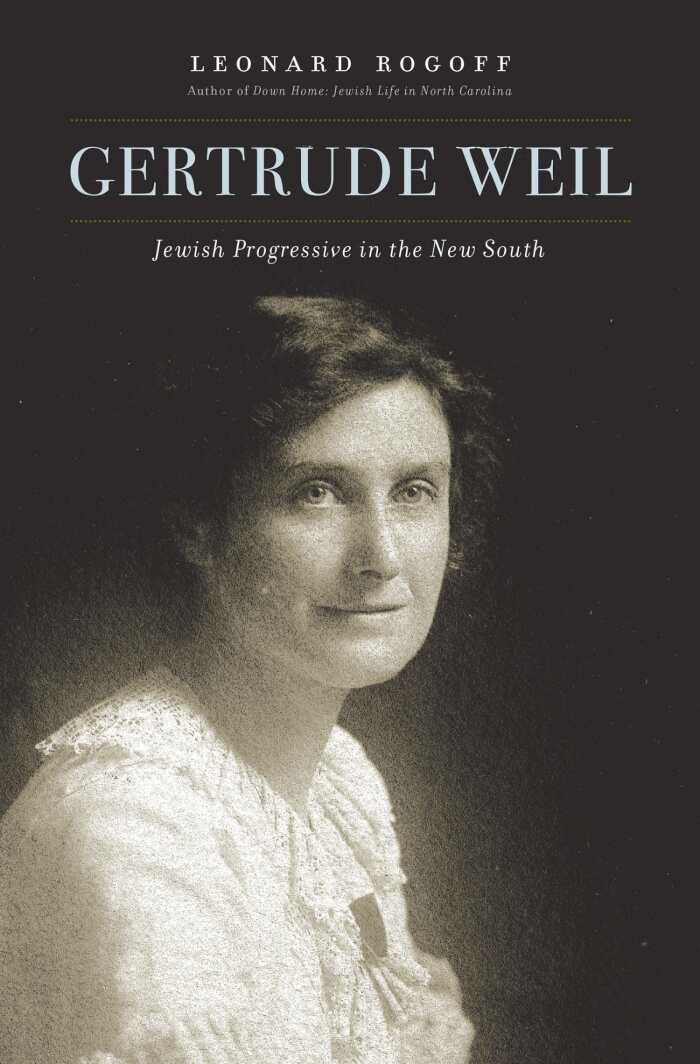

Gertrude Weil

Jewish Progressive in the New South

Leonard Rogoff

The University of North Carolina Press

Hardcover $35.00 (368pp)

978-1-4696-3079-3

The world came to Gertrude Weil’s door, and Leonard Rogoff shows in Gertrude Weil: Jewish Progressive in the New South that she, in turn, bridged worlds. Born in 1879, a North Carolina Jew of German descent, Weil was educated at Smith College but returned to her hometown of Goldsboro afterward and remained active in philanthropic, political, and social causes there until her death in 1971. Her selfless, seemingly tireless advocacy was guided by the principles of Classical Reform Judaism, “moralism, rationalism, and universalism,” and, like Esther, she was a woman born in the right circumstances to act. Weil’s independent wealth, religious values, personal connections, and education allowed her unparalleled access and efficacy in her chosen causes. And she participated in an almost innumerable list: Zionism, labor reform, childhood and adult education, Jewish evacuation during the Holocaust, women’s suffrage, racial equality, birth control, eugenics, Jewish apologetics, and ecumenical education, among others.

Nonetheless, Weil is a difficult person to figure out. A woman whose public persona often diverged from her intensely private personal life, Weil made comments to the effect that she was a woman “straddling eras” who “held a modern worldview without abandoning her Victorian pieties,” and this tension is even more palpable in retrospect. Rogoff tackles the challenge by zooming out to show the larger picture of people, politics, and place surrounding Weil in between shorter personal vignettes. Weil’s activities encompassed such a wide array of local, state, and national causes over such a long period that, at times, the wider picture becomes dizzying. While Weil herself remains somewhat of a cipher, Rogoff explores the unique intersectionality of social moment and movement her life offers.

LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (March 2, 2017)

Jane Crow

The Life of Pauli Murray

Rosalind Rosenberg

Oxford University Press

Hardcover $29.95 (512pp)

978-0-19-065645-4

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Rosalind Rosenberg’s long-delayed biography, Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray, uses the papers of Pauli Murray deposited at Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library to give voice to Murray’s experience in a way Murray couldn’t in her own time. Mentee of Eleanor Roosevelt, mixed-race middle-class Southerner of the Jim Crow era, gender dysphoric, poet, lawyer, professor, Episcopal priest, and civil rights activist, Pauli Murray lived an epic life and laid claim to many identities. Because, and sometimes in spite of this, Murray, a person who never stayed in one place for more than a few years, made a life in social justice.

But, just like the prophet who is not accepted in his hometown, the communities in which Murray worked often found her personally uncomfortable and her work either too radical or seemingly self-obvious. Many overlooked Murray’s role as a visionary, yet her work as a lawyer and activist presaged several major civil rights fights, including racial segregation, private housing discrimination, and gender discrimination, among others. Murray’s efforts culminated in coining “Jane Crow”—a term for the double oppression experienced by black women. “Jane Crow” helped Murray address much of her lived experience but not her gender dysphoria. After early unsuccessful bids for medical intervention, Murray internalized her feelings of “betweenness” and suffered under heteronormative pressures regarding her gender and sexual expression. Ultimately, Murray never experienced the civil rights movement that may have enabled her to name and resolve this experience of her body. Rosenberg tells Murray’s story as she lived it but also casts a well-informed, modern eye on the intersections and omissions within that life. Her striking interpretive work clearly shows what Murray herself suspected: that everything Murray did was “part of history … an instrument for achieving things.”

LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (March 2, 2017)

Accomplice to Memory

Q. M. Zhang

Kaya Press

Softcover $21.95 (352pp)

978-1-885030-52-8

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Trained in anthropology, psychology, and creative non-fiction, Q. M. Zhang brings all these disciplines to bear in Accomplice to Memory, a radical investigation into the nature of truth and memory that’s equal parts biography and memoir, narrative and graphic art. Zhang’s father, Wang Kun, grew up in China in the decades leading up to the 1949 revolution and immigrated to the United States shortly afterwards. Zhang finally decides to tell his story after a health crisis that leaves him with declining mental facilities. When his lifetime of silence breaks down, it’s in scant, often contradictory stories. Although his narrative overlaps major historical events, he always places himself just outside the known. Zhang notes that children of survivors “are afflicted with a strange condition that makes it difficult for them to distinguish between fact and fiction, though they are certain that a clear line can be drawn between the two. They crave truth yet are beset by doubt and suspicion of anything that smacks of it.” All too soon, the deceptively simple task of narrative becomes the greatest challenge of all.

It soon becomes clear that Zhang’s voice is authorial, not authoritative. She often doubles down on her suspicions and doubts, presenting collective historical record, particularly images, as personal family history and then mythologizing that history. Zhang abandons the singular narrative in favor of a troubled, unstable construction that exists between image and text, father and daughter, memory and history, reader and writer, in a stance that claims the collective experience as her own. Zhang offers endless prompts on which to hang the narrative of her father’s life, and as the line between truth and fiction is steadily and deliberately blurred, it becomes clear that all memory is narrative, a construct that’s replayed again and again until it gains saliency and longevity in the mind.

LETITIA MONTGOMERY-RODGERS (March 2, 2017)

Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers