Truth or Consequences

he Stakes Are High in the Natural World

Whether we’re witnessing the sublime beauty of a starlit winter sky or the complex connections among creatures in a forest, the study of nature has the power to change us. As Albert Einstein advised, “Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.”

Understanding the natural world is not just a philosophical endeavor, it is an immediate and pressing need. Our survival as a species is strongly intertwined with the natural world. Nature’s diversity and abundance is giving way to scarcity, and if we continue down this path we will, sooner or later, face the devastating consequences of climate change, shrinking rain forests and wetlands, dwindling water supplies, and other environmental challenges.

Especially because the issues are so difficult, an alarmist view is not helpful. Fortunately, a number of perceptive and persuasive writers and researchers are providing tremendous insight into the complicated decisions we face about our environment and the natural world—while also providing hope. Each of the titles featured here is at once challenging and encouraging, outlining the many factors at play as well as the good work already under way.

In The Kingdom of Rarities (Island Press, 978-1-61091-195-5), Eric Dinerstein, chief scientist with the World Wildlife Fund, offers an extraordinary and engrossing account of scarce species around the world. He expertly considers the factors that contribute to scarcity—many, but not all, related to man’s activity. Whether discussing jaguars in the Peruvian Amazon or Kirtland’s warblers in the jack pine forests of northern Michigan, Dinerstein writes from firsthand experience, having spent twenty-four years studying these species and working with friends and colleagues to save them. With a friendly intimacy, he offers a personal narrative, a travelogue, and a celebration of the natural world, not a polemic. When Dinerstein asks questions about biodiversity, habitat fragmentation, and conservation biology, he is constructive, engaging, and exceptionally well informed. He is also balanced and realistic, daring to ask which species are the most important to protect and why.

Similarly, in Traveling the 38th Parallel: A Water Line around the World (The University of California Press, 978-0-520-95455-7) David and Janet Carle illuminate an environmental discussion on waterways and wetlands with accounts of their travel across the Northern Hemisphere. They spent twenty years as park rangers at Mono Lake Tufa State Reserve in California, and the park’s location on the thirty-eighth parallel helped inspire the clever theme of their global adventure. They find that regions across the globe at that same latitude—from the demilitarized zone on the border between North and South Korea to the mafia-controlled island of Sicily to the tall grass prairie in the Flint Hills of Kansas—face similar challenges related to water supply and ecology. Ambitious projects designed to re-engineer waterways in many cases are threatening the health and viability of those waters and related ecosystems. Likewise, agricultural and urban needs often compete for limited water resources. The authors acknowledge the complexities of these issues while also recognizing the many like-minded people around the world who are working to address the issues in meaningful and sustainable ways.

Waterways are also the focus in Down the Wild Cape Fear: A River Journey through the Heart of North Carolina (The University of North Carolina Press, 978-1-4696-0207-3), in which Philip Gerard offers an adventure story paired with a view of the ecology, history, development, and industry along a vital river that runs from the core of North Carolina to the coast. Gerard, professor of creative writing at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, uses glittering, evocative prose to recount his travels by canoe and powerboat down the Wild Cape Fear River with a guide, biologist, photographer, and others. Partway through his journey, he writes, “Now as we step onto dry land, my eyes are full of the river and my memory is full of birdcalls, conversation, the damp smell of the great locks, the fragile clutch of turtle eggs on a sandbar, herons, hawks, the face-burning wind in the lower river, the hard chop, the great ships churning out to sea, and the towering silence of drifting backward, the only boat for miles in any direction, the river carrying us inexorably exactly where we want to go only because it happens to be going there.” This is a compelling story that offers a striking and thoughtful look at the many environmental, political, and commercial issues affecting this region and the waterway that feeds it.

The White Planet: The Evolution and Future of Our Frozen World (Princeton University Press, 978-0-691-14499-3) also spotlights the ecology of water, but here it is water in its solid form. While most water on the Earth’s surface exists as liquid, the 2 percent captured in ice, also known as the cryosphere, plays an essential role in our planet’s health. Renowned French researchers Jean Jouzel, Claude Lorius, and Dominique Rayaud review the history of the Earth’s ice as well as the history of the study of that ice. This is the most directly scientific of the titles featured here, as the authors explore the “glacial archives” for evidence on climates of the past as well as prehistoric and contemporary climate variations. Offering thorough evidence on a variety of concerns—including shrinking polar regions, the greenhouse effect, and changes in the ozone—the authors outline a clear path to preserve the viability of the cryosphere and our planet.

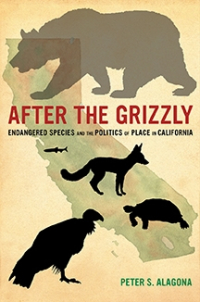

Much narrower in scope, but just as cogent, After the Grizzly: Endangered Species and the Politics of Place in California (The University of California Press, 978-0-520-95441-0) looks at the history of efforts to preserve endangered species in California. An assistant professor of history and environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Peter Alagona opens by reviewing the dramatic wildlife declines in the mid-1800s and the state’s initial forays into environmentalism and habitat preservation starting in the 1880s. He describes an array of environmental legislation enacted since, including the landmark Endangered Species Act of 1973. Chapters detail efforts to preserve the condor, Mojave desert tortoise, delta smelt, and others. Throughout, Alagona notes that habitat preservation has become the primary tactic for preserving endangered species in the US, but he argues that, to truly succeed, environmentalists must think more broadly: “Americans use endangered species as a proxy to fight about so many larger social issues … Yet endangered species have diverse and complex habitat needs that we are only beginning to comprehend. Some require remote wilderness areas … but others can thrive in rural areas, suburbs, or even cities … If we want to protect endangered species and biological diversity, then it is time to rethink the meaning of habitat, and the role of protected areas in particular, in a broader vision for conservation.”

In each of these new releases, the authors are passionate about preserving the diversity and richness of the natural world and are attuned to the complexities of related issues. Throughout, these books teach us much about what we need to be doing—and why it is vitally important to care.

Kristen Rabe is general director of Internal Communications for BNSF Railway, where she oversees the company’s publications, video, and digital communication. She has a master’s degree in English literature from the University of Virginia.

Kristen Rabe