A Natural High: Finding Joy in the Wild

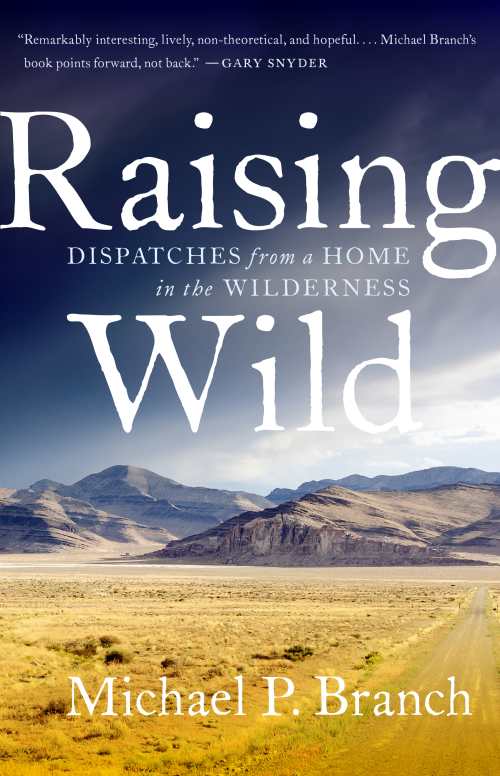

There is a magic that is lost if we choose to view ourselves as outside of nature, as if we are not one of the many animal species that inhabit the natural world. Michael Branch’s newest book, Raising Wild, (Roost Books) is about parenting in the high Sierra, but it’s also an extended, often hilarious, look at what can be gained from living vividly in nature.

Environmental insights and frustrations weave in with accounts of Branch climbing desert peaks with his girls, who help him to find ways to awe anew in vistas that adults sometimes take for granted–from his own backyard, to the vast and storied stars. There are also riotous accounts of drinking and philosophizing in the book; don’t miss the author’s cocktail recipe, which is a cheeky accompaniment to this always satisfying, continually surprising read.

Your book revels in the ways that parenting in the high Sierra has deepened your connection to, and understanding of, the natural world. What invaluable lessons can readers learn from Hannah and Caroline that they could not learn from John Muir and the other solo naturalists you name?

Michael Branch: 'Nature is a site of play, humor, and imagination.'

That’s a wonderful question! I wrote a book on John Muir once (John Muir’s Last Journey), so I’m certainly not out to discredit Muir, or any of the canonical nature writers I mention in Raising Wild. Their inspiration has been vital to me as a writer and an environmentalist. But, with some notable exceptions, mainstream environmental writing has tended to gravitate toward two poles: the jeremiad and the elegy. The jeremiad, a literary form that goes back to the Puritans, is the angry diatribe that points out the reader’s environmental sins and makes them feel ashamed—although, in fairness, it is a shame that is intended to lead to reform, to a new awareness. The elegy, of course, is a stylized way of expressing our grief at loss—and grief is a feeling that anybody who cares about the earth is forced to feel pretty often these days.

But the problem with allowing anger or sadness to become our dominant mode of engagement with nature (or writing about nature) is that so much spontaneity, joy, and pleasure is lost. And that’s where kids come in. In the book I’m careful not to romanticize or sentimentalize kids, but it seems to me that children have a more direct and unmediated relationship to the world than we grownups do. They aren’t as burdened by environmental guilt or fear as we are, and their mode of interaction with the physical world tends to be not only very direct and immediate, but also richly imaginative. They “think” with their bodies, and they know intuitively something that we adults struggle to remember: that nature is a site of play, humor, and imagination, and not just something to worry over and fight for.

Can you tell us a little bit about the experience of working with Roost Books to bring Raising Wild to print?

I’ve been so fortunate to work with the team at Roost. The press is small, creative, and ethically centered—a responsive, human-scale operation that works well for my own sensibility—but it also has the reach that results from their long association with Penguin Random House, which distributes Roost books. Writing is a solitary endeavor, but publishing a book certainly is not. When a reader lifts a book from a bookstore shelf, they tend to focus on its title and author. But behind that cover is a whole team of folks who have to be able to work together effectively—and, if they’re lucky, with a little joy and good humor too. I’ve been so gratified by my collaboration with Roost that I’ve signed with them for my next two books. After Raising Wild, my next Roost book will be Rants from the Hill, forthcoming in summer, 2017.

Michael Branch’s ‘Raising Wild Cocktail’ recipe

What would you like to have readers carry from your book into their own local nature and conservancy efforts?

I don’t intend the book to prescribe or argue for any single approach to environmental engagement. I think our relationship to nature is highly individual, conditioned by all sorts of factors, both internal and external. As an avid reader myself, I tend not to enjoy books that tell me how I should live, since I view my own life as an experiment that I need to try for myself.

That said, I think a few insights generalize pretty well from our unusual life in the remote high desert to anyone who cares about the health of the natural environment. First, I believe that all environmental engagement is ultimately local. We can only protect what we fight for, and we tend to fight for what we love, and we love what we know best. Of course we need to work tirelessly against larger threats including global climate change, but it is easy to be paralyzed by the scope of that sort of problem. If each of us cared more for our home landscape, that would add up to a global-scale shift in environmental awareness, responsibility, and reform. I also hope Raising Wild will remind readers of the importance of pleasure in our relationship to nature. We can’t let our anger and sorrow in response to environmental degradation prevent us from engaging with the physical world. Our species has evolved to need that contact, and in my view we can’t flourish without it. In this respect I follow in the footsteps of environmental activist and writer Edward Abbey, who fought to preserve the wild beauty of the American West but never forgot to make time to enjoy that beauty as well.

You write about places becoming “holy” because of how they are experienced. Outside of your mountain home, can you discuss another place you’ve experienced this way, and say what made it so?

Well, from Henry David Thoreau forward, nature writers have given the trope of holiness a pretty good workout, so I hope I approach this with a lighter touch! It is of course true that there is sacredness in our relationship to the natural world. Nature is our widest and oldest home, and it is a touchstone that reminds us of who we are—of the wild world from which we emerged, and which we cannot afford to lose contact with. But the range of emotions I experience in nature is much wider than reverent awe. I feel fear when wildfire sweeps the dry hills near our remote home; admiration when I note the evolutionary adaptations of scorpions to this extreme environment; excitement when I see a great horned owl drop down on a jackrabbit; frustration when I hear packrats scurrying beneath our floors; surprise when a red tailed hawk drops a live rattlesnake from the sky; calm when I see pronghorn antelope glide effortlessly across the land at 50 or 60 miles per hour. And in our own interactions with nature there is also enough comedy to leaven the loaf; I believe we need to embrace that too.

To answer your question more directly, I’m fascinated by the idea that every place has the potential to hold some form of spiritual power. We don’t always need the sheer cliffs of Yosemite, the sublime chasm of the Grand Canyon, or the vast expanse of the rolling sea to inspire this feeling of reverence. It can and should happen right on our home ground, wherever that may be. I’ve felt this in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, and in the swamps of the Florida Everglades, and I’ve experienced it very often in the deserts of Nevada and the mountains of California. I might evoke Abbey again here. Abbey opened his book Desert Solitaire by writing “This is the most beautiful place in the world. There are many such places.” I think Ed was right.

You’re fairly effusive on the subject of gin. Please conceptualize a high Sierra evocative gin cocktail, and be very specific on the variety of gin that should be used in its concoction.

In fairness, I’m only effusive about gin when I’m not being effusive about bourbon or rye. It is important to have priorities in life. But, since it is still sweet summer, here is my recipe for a new cocktail called Raising Wild.

Michelle Anne Schingler is deputy editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow her on Twitter @mschingler or e-mail her at mschingler@forewordreviews.com.

Michelle Anne Schingler