Gained In Translation: Deep Vellum Brings Great Voices to English Readers

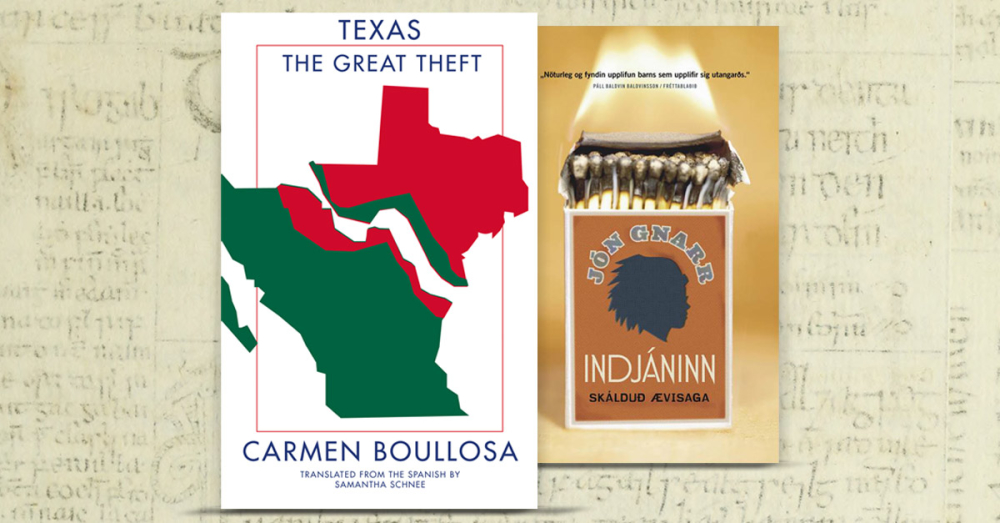

With the release of Carmen Boullosa’s Texas: The Great Theft, and its subsequent short-listing for the PEN Translation Prize, Deep Vellum Publishing, an independent nonprofit based out of Dallas, has established itself as a serious literary house that also brings exciting new ideas of art and advocacy to the table.

Carmen Boullosa

“Getting involved in indie literature and starting one’s own publishing house is an acknowledgment that something is lacking in the publishing establishment,” says Will Evans, who, before launching the translation-oriented Deep Vellum, studied Russian literature and worked briefly as an in-house talent buyer at Austin’s legendary music venue Emo’s.

Evans, who has been a longtime admirer of such small press mavericks as Milkweed Editions and Melville House, is especially enthused about adding to what he see as the increasingly homogeneous literary output typified by works being produced by the Big 5 publishers.

“The literary publishing world has neglected and continues to neglect and ghettoize translations into some alternate universe that exists outside what is published here in English originally and that is tremendously nearsighted and problematic,” says Evans, who explains that he started Deep Vellum “to try to not only publish more translations, but to call attention to those translations published by all publishers, and to get them included in the discussion of the overall American literary culture.”

With print runs between 2,000-3,000 copies, Deep Vellum is definitely working its big plans on a small scale. Evans boasts that the sales numbers for Boullosa’s latest “are already higher than they were for a couple of her previous books that came out from much larger publishers some years ago.”

Indies Serve Strategic Role

As Evans sees it, the concentration of the publishing establishment in New York, coupled with the exclusion of translation’s role in the current literary culture, are some of the biggest problems affecting the publishing world these days.

Independent presses such as Deep Vellum serve a serious and strategic role by providing what he sees as “an alternative to the increasingly homogeneous corporate publishing culture represented by the Big 5 and all their thousands of imprints.”

For Evans, the laudable goal of his press is not merely to bring to readers an awareness of “how awesome independent publishers are,” but to question the value of “the words that they read for fun, excitement, and enlightenment.”

Iceland Excitement

Jón Gnarr

Deep Vellum’s 2015 list is filled with exciting titles from Mexico, Russia, France, and Iceland.

Evans is psyched about all his books but seems especially hyper about The Indian by the former mayor of Reykjavík, Jón Gnarr.

“I’ve been following him, inspired by him and his story, since he formed the joke political party the Best Party in 2009 and ran for mayor of Reykjavík and won,” says Evans. “And now I’m publishing a trilogy of memoir-novels about his insane childhood, dyslexic and ADHD in a time and country where neither were understood.”

To foster this fount of foreign fiction, Evans is relying upon a coterie of world-class translators like Marian Schwartz out of Austin, who has translated over sixty volumes of Russian literature—including works by Nina Berberova as well as Mikhail Bulgakov—and Samantha Schnee, the founding editor and chairman of the board of Words Without Borders, an essential resource for translation hungry readers that manages to publish eight to twelve new works by international authors a month.

“I have a close relationship with several translators and their recommendations have guided me into signing a lot of these first several years’ of titles,” says Evans.

Ushering in New Voices

George Henson, a translator based out of the Dallas area who has been working on Sergio Spitol’s monumental mediation/memoir The Art of Flight for Deep Vellum, speaks to the importance of independent publishers in the current literary scene.

“The big guys are looking for the next big writer, and if he is obscure, all the better because the narrative adds to the marketing. In the end, though, it’s very hard to take a chance on unknown writers,” says Henson, who has translated authors such as Elena Poniatowska, Miguel Barnet, and Andrés Neuman.

Henson places a high priority on the need for small presses to help usher in emerging voices. “The new writers are usually discovered by the independent presses,” Henson says. “New Directions, for example, has a long history of publishing translation, Graywolf, Open Letter, Two Lines, and now Deep Vellum.”

Agonizing Over Words

Focusing on translation, Deep Vellum has set itself up for some heavy literary lifting as well as a large degree of responsibility. “Translation is stressful regardless of the stature of the writer,” says Henson. “No one second-guesses himself more than the translator.”

Henson describes spending an entire day agonizing over a single word. “If the translation is superb, the author gets the credit. If the translation doesn’t read well, the translator is blamed,” Henson laments.

Schnee, whose work on Deep Vellum’s inaugural publication, Texas: The Great Theft, has received much praise as well as earned Typographical Era’s 2014 Translation Award, speaks of the problem inherent in trying to capture the author’s voice.

“I recall Carmen saying to me during the editing process that she felt the voice of the narrator of Texas had changed in the translation, and at first I was really worried that I had done something to alter the voice of the narrator unintentionally,” says Schnee.

When the UK-based translator went back over her work she couldn’t find anything that seemed to her like a deliberate departure from the text, and began to wonder about the nature of translation itself.

“Perhaps it is not unlike rendering a painting on a different media, watercolor versus oil, for example,” she muses, going on to entertain the possibility that perhaps “the final work, as in all art, is in part a reflection of the medium in which it is created.”

“Would Monet’s water lilies have the same impact in watercolor that they have in oil paint?” Schnee asks.

Challenges in an Insular Country

Speaking of Texas: The Great Theft, which he calls a perfect choice for Deep Vellum to launch with, Evans notes that he has been ecstatic with the response in the press, while conceding that there might have been those who would take issue with the book’s particular Mexican perspective on Texas history.

“This problem of closed-mindedness to outside opinions is something that is not new to America, but which we’re seeing the consequences of on a daily basis in our relations with the rest of the world as our country becomes ever more insular,” says Evans.

Translation is a tremendously political issue for Evans, a self-described feminist who admits that there are authors he won’t work with for political and ethical reasons.

At his core he believes that no work is untranslatable. “People are always asking me, ‘Isn’t something lost in the translation?’ I’m not focused on that ineffable something that is lost, I’m focused on the effable that is gained from translation. Which is the whole world. Which is everything.”

Roberto Ontiveros is an artist, critic, and fiction writer based in Austin, Texas. Short stories of his have appeared in the Threepenny Review, the Santa Monica Review, and the anthology Hecho en Tejas.

Roberto Ontiveros