Cuban Sci-Fi: Viva La Dystopia

Cuba has been, in many ways, preserved in amber during more than a half-century of Cold War and continuous US embargo. But just because you can’t find a US car model from later than the early ‘60s does not mean Cuba’s culture hasn’t experienced some evolution even in its isolation. That’s why, when President Obama and Cuban President Raúl Castro shook hands earlier this week, there was a more-than-symbolic opening of doors to see how Cuban culture has developed on its own. Ilan Stavans, publisher of Restless Books, was curious, and what he found was a wonderfully pleasant surprise: Cuban science fiction. The isolated island nation is not a place where you’d think sci-fi would thrive, but most good science fiction is usually a hidden commentary on our own societies. Under Castro, sci-fi was a perfect way for Cubans to describe their own particular present-day dystopia. Below the news, Stavans tells FTW about some of the far-out authors and books he found in Cuba and is bringing to the English-speaking world.

First, the News

Girl Power: These fifteen feminist YA novels represent teen girls accurately: They’re brave. They’re smart. They’re capable. They know what they want. Dive into any one of these books and help to give these people and this genre the credit they deserve.

Get Your Wild On: Genetically, you’ve got the right stuff to do battle with woolly mammoths. Done any fight-or-flighting lately? These books will help you tap those special powers.

What Authors Want: After conducting the most comprehensive survey of what authors think of their publishers, literary consultants Harry Bingham and Jane Friedman shared their data and provided interesting conclusions about how well publishers are doing in serving their authors’ needs. Here is the extensive analysis.

On Hold Indefinitely: Sometimes big publishers might decide to cancel a book or a series before it’s published. Agent Carly Waters explains why this sometimes happens and what you can do about it. (Hint: one of the options is self-publishing.)

E-Book Profits: Rumor has it that e-books are profitable for indie authors, sometimes more so than print. But is there really that much money in e-books? Now Novel shares an awesome infographic with fascinating statistics about their market share and platforms.

False Distinctions: A war between genre fiction and literary fiction continues in some circles. Here is writer Amira Makansi’s take on why genre fiction deserves to be called “great literature.”

Ilan Stavans

Cuba has been described as a place frozen in time. What is different about the science fiction produced by a people who are, in many ways, sudden time travelers to the twenty-first century?

Ilan Stavans

Cuba is a utopia gone sour. (Don’t all of us live in something like that?) Science fiction there is more than a hundred years old, meaning it starts before Fidel Castro dreamed up a dystopian future in the Sierra Maestra in 1958. But the crop of SF writers active under Communism is particularly intriguing; they write about alternatives realities with the full knowledge that they live in one of them. Of course, the argument should be made that SF, no matter where it comes from, isn’t about the future; instead, it is a veiled depiction of the present. In the case of Cuban SF, this argument is decisive; metaphor is king where metaphor prevails.

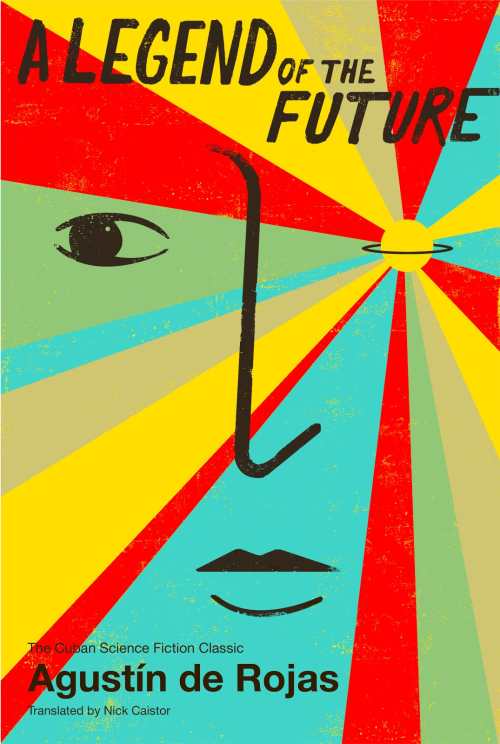

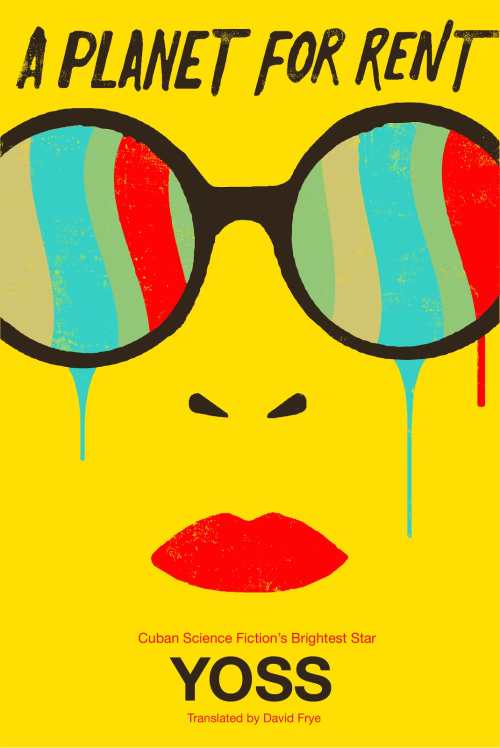

Tell us about A Legend of the Future and A Planet for Rent. What in particular distinguishes them as Cuban sci-fi?

They have a unique sensibility. Indeed, these are two classics of Cuban science fiction. Agustín de Rojas, considered the father of the country’s genre, was the author of a canonical trilogy of which A Legend of the Future is one installment. Restless Books will bring out the other two. He spent his last years (he died in 2011, in his native Santa Clara) telling everyone Fidel Castro didn’t truly exist. He is influenced by the Soviet tradition, which prevailed in Cuba in the seventies.

Yoss (his full name is José Miguel Sánchez Gómez, and he lives in Havana) is the Ray Bradbury of Cuban SF, a prolific polymath, and a close friend of mine, who looks like a character from Game of Thrones. (By the way, Restless Books has, forthcoming, The Voyage, by Miguel Collazo, another classic novel of Cuban SF.)

From Vaclav Havel to samizdat literature in the former Soviet Union, why do you think it is often writers of fiction who push the boundaries in repressive governments?

Writing is a lonesome trade, and writing “against” someone justifies the effort. After the Second World War, the literature of Latin America defined itself against the tyrants (Perón, Pinochet, Trujillo, etc.) whose regimes were machines of oppression. The result was a bouquet of extraordinary novels, including Gabriel García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch and Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat. I am of the opinion that dictators should be thanked—wholeheartedly!—for having given us, tangentially, these master works. Ironically, the only tyrant who so far doesn’t appear to have generated a novela del dictador is Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez. (Nicolás Maduro, Chávez’s successor, is too mediocre to motivate anything.)

Talk a bit more about Yoss. With his heavy-metal-style outfits and long hair, he’s not what many in the United States would expect a Cuban author to look like.

Yoss

Frankly, I don’t know if anyone in the United States expects sci-fi to come out of Cuba—or, for that matter, from Latin America in general. The region isn’t known for scientific and technological innovation, which are the seeds of SF. Aside from being an adorable—and adorably anachronistic—character, Yoss has, in my view, a heroic trait. In a country where information isn’t free (and, of course, neither are people), he always seems up-to-date. Without Apple and Google, without Facebook and Twitter, that, no doubt, is miraculous! Whenever I communicate with him electronically, and the speed of response is relatively fast, he talks to me as if he were in outer space, always using the lingo of astronauts of the sixties. Life is made bearable by friendship, and Yoss’s presence in mine is a joy.

This is an exciting time for Cuban and American writers to become reacquainted. Cuban science fiction is a refreshing surprise. Are there other genres with uniquely Cuban accents?

I hope to introduce, through Restless Books, a line of hard-boiled Cuban detective novels that are an invaluable prism through which to understand justice on the island—and its counterpart, prejudice. As the United States and Cuba become reacquainted (and I confess a certain no sé qué that borders on apprehension), I look forward to a deeper, less stereotypical appreciation of Cuban culture through an extraordinary treasure-trove of literature, beyond the marquee names, that is still untranslated into English.