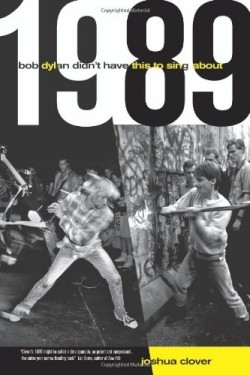

1989

Bob Dylan Didn't Have This to Sing About

In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, marking the end of the Cold War-as well as the end of history itself, according to the writer and philosopher Francis Fukuyama. In his new book 1989, pop culture critic Joshua Clover argues that although Fukuyama’s declaration of the death of history was premature, the popular music of 1989 embodied the same anti-historical zeitgeist captured by the influential academic’s famous assertion. Clover-an award-winning poet, a professor at the University of California-Davis, and the author of a book about The Matrix-analyzes the popular and historical discourses of 1989 in depth, and finds that the two were essentially indistinguishable. “History is now pop,” he contends, “and pop, history.”

Clover knows the music of 1989 well, and succeeds in positioning artists as diverse as Nirvana, Jesus Jones, the KLF, and NWA within the context of the political and aesthetic upheavals of their era. He offers an astute take on the evolution of the European acid house genre and its associated rave culture, noting the commonalities between rave’s psychedelic communitarian impulse and the youth culture of the 1960s. Although he stumbles when attempting to cram the complex ideological history of punk rock into the space of only few pages, Clover makes a convincing argument that grunge represented a retreat from the political engagement of punk into the angst-filled interiority of bands like Nirvana. He observes a similar pattern in hip-hop fandom’s abandonment of politically-conscious acts like Public Enemy in favor of the nihilism, violence, and materialism of gangsta rap. According to Clover, ravers, gangsters, and grunge bands alike all saw themselves as “outside of history,” insofar as they were uninterested in using their art to position their personal experiences within a broader historical or sociopolitical context.

Clover’s approach throughout is thoroughly academic-readers with a low tolerance for jargon or for extended discussions of the theories of Frederic Jameson and Theodor Adorno may want to avoid this book altogether. But those who share Clover’s intellectual love of popular music will find much of interest in 1989, and will appreciate his vivid snapshot of a tumultuous moment in pop and history.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.