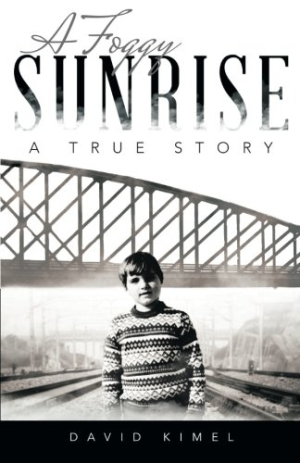

A Foggy Sunrise

This powerful memoir of wartime Romania brings back the horrors of war mixed with the resilience of childhood.

In his beautifully crafted memoir, A Foggy Sunrise, David Kimel describes his childhood growing up in Bucharest, including the lean and fearful times of World War II. He provides vivid snapshots into a time and place he witnessed, but also demonstrates how he was always sustained by his strong and guiding parents.

Kimel—now in his early eighties—tells of the marriage between his mother, from a well-to-do family in Bulgaria, and his father, a Jewish man from Romania, whose own father was a native of Poland. From this melting pot of ethnicities, the author reminisces about how his extended family supported one another when times were difficult.

Kimel’s own family—including younger sister Simona—was forced to move from apartment to apartment over the years when money from work could not be stretched to cover expenses. But the author recounts this all from a young boy’s perspective, noting that he was intrigued more with a toy than his brand new sibling.

The majority of the book chronicles his life from ages three to thirteen, when he celebrated his Bar Mitzvah. The remaining fifty pages tell how he and various relatives emigrated from Romania to make their homes in other countries.

The author—a resident of Canada for nearly forty years—is a talented writer, creating a sense of place from his memories of Bucharest. The German army occupied Bucharest for most of the war years; Kimel relates that while some Jews were singled out by the Legionnaires—green-shirted vigilante hooligans who were similar to the brown-shirted storm troopers—it was largely left to the local government to deal with any “Jewish problem.” Bombings by the Allies and their aftermath affected the citizens, but because children are resilient, the young David looked forward to finding “treasures” in the wreckage.

Conscious of his audience, he translates Romanian words for easier understanding, placing the English term in parenthesis, such as Piața Mare (the Big Market) and Podul Izvor (Izvor Bridge). He expands on cultural customs, recalling that it was normal to address all elderly people as Aunt and Uncle, whether or not they were relatives.

Using vivid descriptions and the most minute of details to depict the places and people of his past, Kimel recalls this about his school: “A double wrought iron gate door was guarded by an old man sitting inside a little booth that had a sliding window.” He describes the man inside, the father of the school secretary, as “a little, thin man with glasses, and his red hair cut short.”

Many figures from his past are brought to life: teachers at his all-boy vocational school who earned nicknames from the students; his many relatives (and their many peccadilloes) who resided in nearby towns; playmates, both good and bad; and even one or two adults who took advantage of unsupervised children.

The most memorable, however, are Kimel’s parents. He recounts how he missed being with them and Simona prior to their deaths, and so spread out photos on the floor to remember: “The little images imprinted on paper brought back the stories of our lives, the precious moments that bonded each of us together … and I knew that from now I alone, I have the duty to preserve their lives and their memories.” These photos would have been a great addition to such a personal story.

This powerful memoir leaves a lasting impression as a glimpse of a time and place that is no more.

Reviewed by

Robin Farrell Edmunds

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.