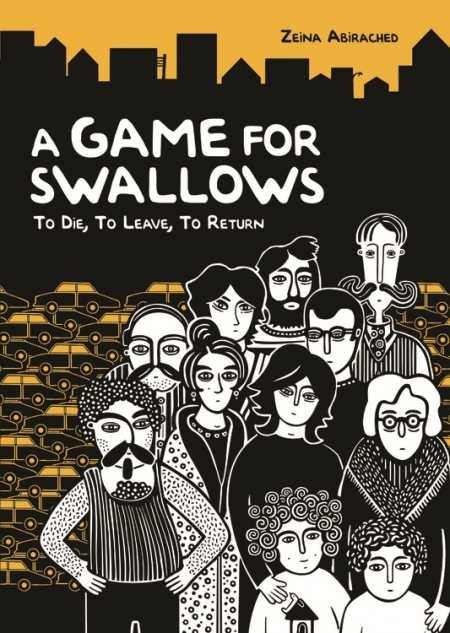

A Game for Swallows

To Die, to Leave, to Return

Zeina Abirached’s evocative memoir, translated from French and told in a graphic novel format, opens with an attractive skyline of East Beirut in 1984. As the perspective zooms in, the initial beauty gives way to empty streets, windows protected by cinder blocks, rooftops lined with barbed wire, electrical wires dangling from homes, and rows upon rows of steel drums indicating the Green Line, a demarcation separating Muslim and Christian factions during the Lebanese Civil War, which took place from 1975 to 1990. The author’s apartment building looks out over this troubled area.

On the evening this story takes place, a young Zeina and her even younger brother, await the return of their parents, who have gone to visit their grandmother. Although she only lives a few blocks away, her apartment is situated on the other side of the Green Line and requires Zeina’s parents to follow a precise path to avoid sniper fire. One by one, Zeina’s nine apartment neighbors gather in her tiny foyer, an interior and therefore safer room in the building. Among them are Chucri, whose taxi driver father was murdered at the beginning of the war and whose generator keeps the building running during routine blackouts, a young couple expecting their first child and awaiting emigration to Canada, and Ernest, a former high school French teacher whose identical twin brother was killed by a sniper.

Reminiscent of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, the black-and-white artwork, at first glance minimal and stark, keenly displays these neighbors’ wide range of emotions. As they drink strong Turkish coffee and eat stouf (a cake made of flour, oil, sugar, and turmeric), the neighbors play cards, act out scenes from Cyrano, and discuss baby names while trying to forget the noise of gunfire outside and the growing absence of Zeina’s parents. Their time together underscores the toll the war has taken as Farah, always carrying a small bag with passports and ready cash, shows off wedding pictures she keeps in a box, one of her few possessions after her last apartment burned.

Despite the war around them, these neighbors have never forgotten community and compassion. Chucri contributes lettuce (washed, when there is no running water) to the meal. The neighbors’ simple sharing of food and memories eases fears on this particularly violent night. While this thought-provoking memoir educates American readers on this foreign war, it also encourages them to appreciate their own freedom, safety, and comforts and to build their own communities. One night can change a lifetime.

Reviewed by

Angela Leeper

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.