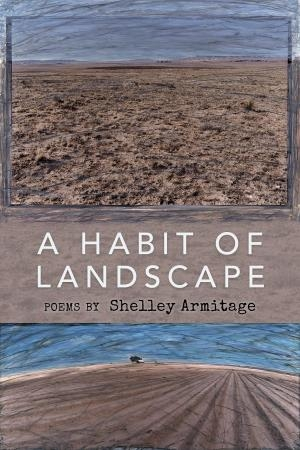

A Habit of Landscape

The empathetic poetry collection A Habit of Landscape adopts a poetics of the outward, turning over subjects both near and far from its Southwest roots.

Shelley Armitage’s slim poetry collection A Habit of Landscape celebrates the history and ecology of the Chihuahuan desert, as well as the concepts of land and landscape more broadly.

Across twenty-eight poems in three sections, Armitage moves between conversational lyrics, narrative poems, and abstract linguistic embodiments of flora and fauna. Though the book’s entries are ecopoetic, they are also atypical for their lack of concern with theoretics around the Anthropocene, personification, projection, and the ethics of observing. Instead, they lift the veil of abstract theory, revealing raw, immediate interactions with the natural world.

The collection starts with two definitions of “habit” and “habitat” that relate the word to ideas of dwelling and holding. It’s this holding, this capturing of tension between human and animal, that the book navigates. The poems are upheld by wondrous language and sound work, as in “Antelope and I”: “Side set eyes catch worlds in their orbs / long lashes like sunshades. / Nervous, curious—your Pleistocene genes / still bolt, then stand.”

In describing encounters with cedar waxwings, foxes, and antelopes, the entries balance adoration, awe, and alienation. They build to a final encounter in “Blue Heron” and the question “What world of yours do we inhabit?” They also admit to the limits of their subject interactions: “We could never be that close / —to appreciate your mundaneness— / without stuffing you.” Still, they hold fast to the principle of reaching across boundaries as much as is possible: “But still I come looking for you / and more: a habit of landscape / which says continuity.”

There are human-focused poems as well. These focus on coming of age and gender in the rural Southwest, as with “Counting Cattle with the Fathers,” in which the land and landscape are an inheritance and an echo that “whisper in the blood.” These echoes widen to include the sound of music inside a womb in “Invitro Bandstand” and the “precise sentences from the other side” in “Palimpsest,” whose use of parenthesis allows a multivalence of readings.

Certain poems contain a degree of prose and slack lineation, and a few endings miss their mark, such as in “Cecil.” In this poem, the killers of the famed lion are allowed to leave the poem reaffirmed in their positions as “kings” over the creature. This lack of reimaginative power prompts questions around the central urgency behind such entries, whose angles of engagement and investment are unclear.

The poems collected in A Habit of Landscape rebuke the notion that there is some fundamental division between people and the natural world, seeking out the places where continuity holds between subjects. Here, everything has a way of making it into “another of your stories.”

Reviewed by

Sébastien Luc Butler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.