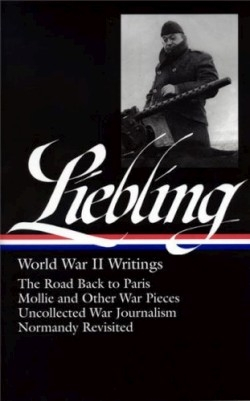

A.J. Liebling

World War II Writings

Before leaving for France on June 10, 1940 as the sole reporter for the New Yorker, A.J. Liebling had been keeping the company of “prize fighters’ seconds, Romance philologists, curators of tropical fish, kept women, promoters of spit-and-toilet-paper night clubs, bail bondsmen, press agents for wrestlers, horse clockers, newspaper reporters, and female psychologists. I was writing excellent pieces about sea-lion trainers and cigar-store proprietors for the New Yorker, and I was happy.” Hitler had seemed “revolting but unimportant” and the destruction of France unthinkable. “After the Munich settlement, I began to be anxious,” he writes.

So begins over a thousand pages of reportage and storytelling by the man who once wrote, “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” A.J. Liebling was born in New York City of an Austrian father. (In the same essay cited above, “Reflections in a Cul-de-sac,” he talks about the succession of German nannies that passed through his house and says, “Anybody who had a German governess could understand Poland.”) Liebling attended Dartmouth College, but was expelled for poor attendance at chapel. After graduating from journalism school at Columbia, he loafed about at this and that, collecting allowances from his father, until he landed a job at the New Yorker in 1935. He would continue to write for the magazine until 1963, the year of his death.

The Library of America volume collects all of his war correspondence under one cover. The reporting runs from Paris, Lisbon, London, Tunisia, and Omaha Beach. Sometimes there’s travelogue: “Norgaard often said that southern Tunisia reminded him of New Mexico, and with plenty of reason. Both are desert countries of mountains and mesas, and in both there are sunsets that owe their beauty to the dust in the air.” There’s deadpan description: “A tanker is a kind of ship that inspires small affection. It is an oilcan with a Diesel motor to push it through the water, and it looks painfully functional.” There’s advice: “The worst thing an interviewer can do is talk a lot himself. Just listening to reporters in a barroom, you can tell the ones who go out and impress their powerful personalities on their subject and then come back and make up what they think he would have said if he had had a chance to say anything.” And, there’s emotion:

Although I believed that in the United States, as in France, the para-Fascists were more dangerous than the Communists, the latter caused me considerably more personal annoyance, because a number of my friends had listened to them. I never expect to see eye to eye with a Ford Personnel manager or the vice-president of an advertising agency, and it causes me no anguish at all to find myself in disagreement with a newspaper publisher. But I did hate to drop in on a perfectly good reporter or physician and find myself howling and banging the table because he thought that there was no choice between Churchill and Hitler and demanded who were we to object to the slaughter of a couple of million Jews in Poland when there were resort hotels right here that wouldn’t take Jewish guests?

In the latter section of the collection Liebling revisits some of the events—large and small—that he couldn’t write about while they were happening, but which stayed in mind nonetheless. A chronology of the author’s life, notes, and index round out this amazing document of war and life. With humor, outrage, and real enthusiasm for the way folks talk, Liebling’s prose honors the times, the people in it, and the New Yorker.

Reviewed by

Heather Shaw

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.