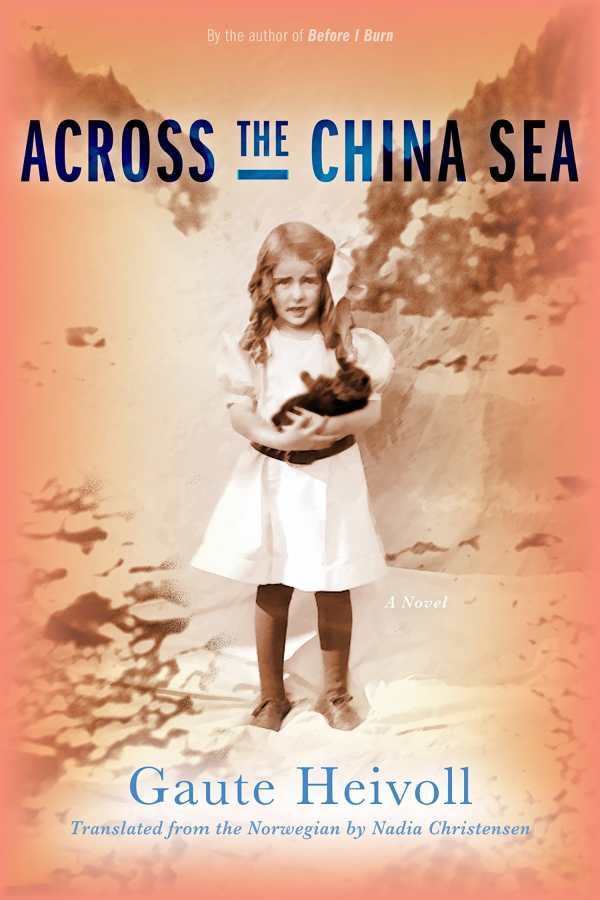

Across the China Sea

A quietly luminous narrative follows five displaced children and reimagines the notion of family.

In Gaute Heivoll’s Across the China Sea, a son returns to his childhood home in rural Norway, prepared to clean out the house following the deaths of his mother and father.

There are possessions to be sorted through, documents to be reviewed—all familiar tasks for the heirs of elderly parents. This house is rather special, however, having been a place that five foster children and three men labeled “mentally disabled” also called home for many years.

Gliding from present to past, Across the China Sea details how the children were taken from their mentally challenged parents after being found half-starved and living in squalor. The father of the unnamed narrator felt that his true life’s purpose was to care for the mentally troubled; he and his wife had always longed to go back to his hometown in southern Norway to start what he called “his own asylum.”

As World War II ends, the couple, with their young son and a new baby on the way—and with the five displaced children—moves from Oslo to the countryside, amid mountains, forests, and fields. Here the children have the chance to live in a stable environment with their foster family, and, as per a governmental contract, be provided with healthy food, their own beds, clean clothes, and work adapted “to their ages and abilities.”

There are no dramatic breakthroughs in Across the China Sea, but a quietly luminous narrative follows the children and the other mentally challenged men through the decades, offering a perspective of individual dignity. Their unique personalities are warmly recalled, and there is a sense of enduring care and concern. Life undoubtedly improves for “the siblings,” although mandatory sterilization is performed by the government upon the eldest boy and girl, an event noted by the narrator with veiled detachment.

Across the China Sea offers an eloquent and reflective look at the mentally challenged, their caretakers, and at Norway’s fixedly pragmatic treatment of mental illness. It also broadens the concept of who makes up a family unit, and the poignant and collective memories that even non-traditional families can leave behind.

Reviewed by

Meg Nola

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.