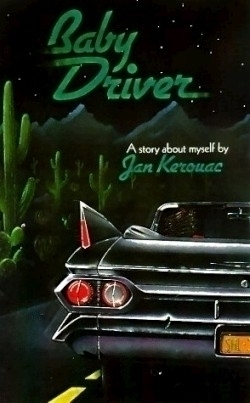

Baby Driver

“That’s not writing, it’s typing,” Truman Capote said after reading Jack Kerouac’s On The Road. Can Jack’s daughter Jan, who only saw him twice in her life, “type” any better? Thunder’s Mouth Press is reissuing Baby Driver, originally published in 1981 by St. Martin’s Press, the first in a planned trilogy of Jan Kerouac’s memoirs. This expanded edition includes letters, poems, and journal selections from her correspondence with Jack’s biographer Gerald Nicosia (Memory Babe). In this debut Jan takes us from her rootless childhood on the Lower East Side with her hard-luck waitress mom Joan and a couple of younger siblings, through the hippie communes of New Mexico, and finally down to Mexico and Costa Rica to Colombia.

Jan wastes no time emulating papa Jack, getting into weed, coke, smack, alcohol, turning tricks, juvi homes, the nut house, peyote, LSD, the whole trunkload of Gonzo physical condiments, before she’s 22 and you’ve read 200 pages. Jan steals money from the poor box at St. Mark’s Church by putting her bubble gum on the end of a candle-lighting stick as a little girl, and gives birth to a dead baby girl in Mexico before she’s 16. There is little reflection in between, as chapters alternate between childhood experimentation and vagrant hippie excesses.

Jan’s descriptive images are excellent, from the black “rat-stabber” shoes of her Puerto Rican schoolmates and the “wretched tomato-macaroni slop” in the cafeteria, to the dancing Technicolor undulations of breathing plants during an acid trip. But the delivery is all so matter-of-fact. Her prose never takes flight as Jack’s did, never sweeps you into the blazing saxophone, smoke-filled throbbing mystical night. She’s always straight-faced, tough, detached, emotionless. In his introduction Nicosia refers to his initial review of Baby Driver in 1981, wondering “where are her emotions?” This life of “abandonment, poverty, beatings, imprisonment, loneliness, madness, and sexual and psychological abuse” is described with no sense of misery, wounding, or scarring. And that emotional void is what is most disturbing about this book. Jan Kerouac completed the sequel Trainsong in 1988 (Henry Holt). Nicosia’s introduction hints that Jan manages to include some feelings in that novel. His read is that she stuffed her feelings so far down during the trauma of her life that she couldn’t easily open that bag of sorrows no matter how much she typed. In Baby Driver we get the facts of Jan Kerouac’s short horrific life deftly described, but apparently unfelt. Given the pathologies of her life, maybe it’s better this way. She suffered kidney failure at age 39 and died in 1996 at the age of 44.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.