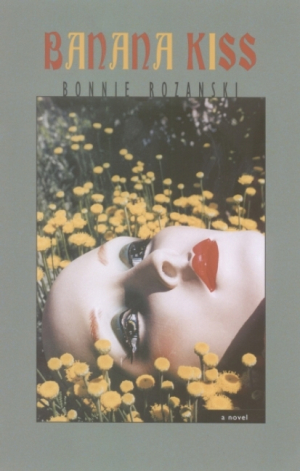

Banana Kiss

“I like my voices. They keep me company.” Within a few pages of this novel, the strength and delicacy of its narrator, Robin Farber, comes through with an honest poignancy. The tone kickstarts her journey and never lets up, even though her voices alternately howl and whisper, and sometimes fall silent.

A resident of a psychiatric institution, twenty-two-year-old Robin seems at first to be falsely imprisoned in a ward where she doesn’t belong, and improperly given medications that make her mind hazy or her mood sharp-edged. But slowly, as she describes her world, it’s easier to see that hers is a schizophrenic realm, where disembodied voices are old friends, and that the line between sanity and mental illness is a blurry one. Even her favorite game, the familiar “name game” tune—and genesis of the book’s title—is a kind of fractured singsong in her head, as one of the institution’s employees, Alex, becomes “Alex Bo-balex Banana-fana-fo Falex Mi-my-mo Alex.”

Banana Kiss is the author’s debut novel, although, with degrees from three universities, she has experience in education and business, and has written several science-influenced books and two prize-winning plays. Readers will hope that this is the first of many novels, given Rozanski’s gift for characterization. Robin isn’t the kind of innocent-in-danger seen in some novels about mental illness, nor is she a caricature of insanity, in which voices direct her to act in horrible ways. Instead, Rozanski creates a woman with a universal quality, who could be the reader’s sister or friend, or even herself.

In pondering her current condition, Robin mixes imaginary events with visits from “real” people—although, since it’s told from her point of view, it’s difficult to tweeze the real from the imagined. Into the blend also go her ruminations on her past, and on the breadth of all she doesn’t know, including slightly twisted assumptions that she’s come to believe. “Here I was thinking that apples are red regardless of whether I looked at them or not,” she thinks. “Or that the tree that fell in the forest really fell, even if I wasn’t there to see its huge trunk crashing down into the earth, bark flying, a sea of branches crushing innocent little rabbits and snakes. I thought it wasn’t up to me to watch something in order to make it happen. Ha!”

Ultimately, Robin is a heartbreaker, because she is so vibrantly written that her isolation and compassionate nature make her psychosis feel real, and elicit sympathy at a much deeper level than would have occurred in a novel that didn’t originate from within her fractured mind. Because there are few major events in the book, with action dwelling instead on Robin’s long days and shadowy nights, Rozanski wisely concentrates instead on making Robin as tangible as possible, and because of this she lingers long after the last page.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.