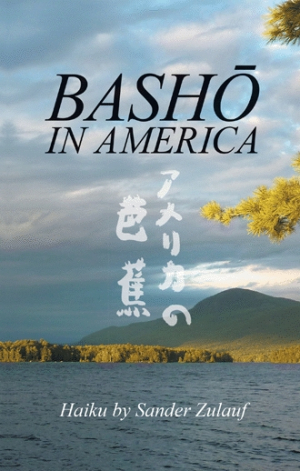

Bashō in America

While each haiku stands on its own merit, the collection, read from beginning to end, is linked by tone and subject matter.

Poet Sander Zulauf’s haiku collection Bashō in America takes its inspiration from Matsuo Bashō, a famous seventeenth-century Japanese master of the form. This inspiration extends beyond poetics to a re-creation of the circumstances under which Bashō wrote some of his poems—by a lake, surrounded by trees, birds, and nature’s bountiful muse.

Zulauf wrote most of the collection on sabbatical from County College of Morris in New Jersey, where he teaches creative writing and English. He stayed in an island cabin on New York’s Lake George. He calls the cabin his “abode of illusion,” an important, central image that derives from the name of the house Bashō stayed in by Lake Biwa northeast of Kyoto, Japan, in 1690.

Each of Zulauf’s haiku can stand alone, yet they harbor a deliberate order, following one another in tone and subject matter, which lends an epic quality to the work. They touch upon the surrounding natural world—butterflies, birds, flowers, deer. Several dwell fondly upon arachnids: “spider on my porch / spins silk in radial nets / fishing for insects” and “on the kitchen wall / daddy longlegs reaching out / to touch my finger.”

Zulauf also ventures into more personal, enigmatic territory, like aging, sex, and other people: “heavy clouds descend; / black mountain disappears; / two lost children too.” Who are these children? Is the black mountain a specific one, a universal symbol, or both? The haiku’s brevity brings into focus how much a poet chooses to reveal or leave out.

All the poems are written in lowercase, even proper names like Vermont and Bashō. There is only one exception: “i will wait all night / to see the pine shadows at dawn / greet the living God.” Not surprisingly, Zulauf was the first poet laureate of the Episcopal Diocese of Newark. His wife, photographer Madeline Zulauf, shot the book’s cover photo of Lake George. Overlaid Japanese calligraphy lends the image an Eastern flavor. Zulauf has published several poetry collections including Where Time Goes and Living Waters.

Interspersed throughout the collection are excerpts from Bashō’s book, translated by Sam Hamill, Narrow Road to the Interior and Other Writings. Alongside Zulauf’s haiku, these take on a call and response quality. One particular quote seems to get to the crux of Zulauf’s goal: “Bashō was struggling to achieve a resonance between the fleeting moment and the eternal, between the instant of awareness and the vast emptiness of Zen.” Haiku is a tool for that paradoxical intersection of the fleeting and eternal, and Zulauf wields it expertly.

Reviewed by

Olivia Boler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.