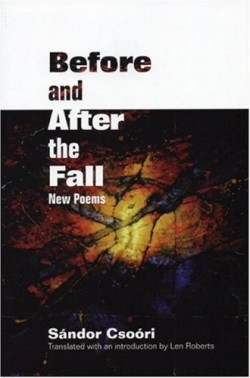

Before and After the Fall

“We are nobodies, / nobodies, just the lost guests of the moon.” In this volume, Hungary’s most prestigious poet leads readers into a post-war world where history, politics, and the struggle with individual conscience create a surreal personal landscape wholly foreign to the affluent West.

Born in Hungary in 1930 and having lived through World War II, the Soviet occupation and Hungarian revolution of 1958, and subsequent political oppression, Csoóri has a worldview marked by the omnipresence of history as a formative force. His poetic voice, similar to other Eastern European post-war poets, takes on an objectivity and distancing that captures the psychological strategies adopted by the creative and those who took conscientious stands against the state.

The translations do justice to Csoóri’s impersonal tone. Roberts, a recipient of Fulbright Fellowships and a National Endowment for the Humanities Award for translation, delivers an English that is spare, precise, yet redolent with multiple associations: “her apron, slipping not and then, smells of parsley and chives- / The sweet scent of her long-gone garden sending me to sleep beside you tonight again.”

In his introduction, Roberts discusses the challenges Csoóri faced coming of age in totalitarian Hungary, and how those challenges inform the work: “Insisting it is the individual’s responsibility to retain integrity in the face of the depersonalizing modernist and socialist society—and the consequent idea that an individual who does not retain such integrity has betrayed both himself and his country, Csoóri returns again and again to this sense of betrayal and guilt.”

For American readers who have never experienced the pressures that Csoóri describes, the poems provide a portal through which to examine the Hungarian experience and, by reflection, their own. While Csoóri’s existentialist despair is unique to his social experience, his unrelenting vision of a hopeless world challenges readers to view their own experience in new ways, especially during this time of political turmoil: “Smoke, smoke, poisoned dust and the gang of poisoned words roam among our quiet hours.” While Csoóri addresses the guilt of surviving in a corrupted world, his hope is more poignant for its pragmatism: “But you must learn at last / to stay here at this place / of ruin: in the land / of leprous walls and snapped-off door handles.”

Csoóri’s poems, not light reading, carry a weight of consequence that, in contrast to much American poetry today, awakens readers to significant questions, for when Csoóri writes, “you’ll worry when the army arrives, / when the commandos in black / headdress arrive,” readers can not turn away from this witness of history. Csoóri’s poems, as strident as a whispered plea in a darkened room, remind readers to be vigilant and not to cede hope to the propagandist dream weavers: “Can you hear / this purely green, purely slimy, purely / corpse-heavy hope-sentence, too, my friends.”

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.