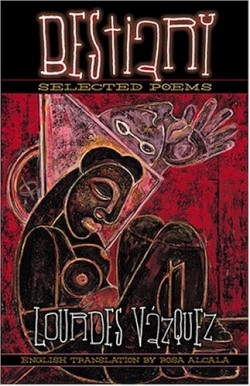

Bestiary

Selected Poems 1986-1997

With more than typical Latin fierceness, this series of prose poems by a native Puerto Rican twists the traditional meaning of the title word to introduce a new concept of beastliness. As themes and language evolve, the sometimes hidden, often overt, passions that inform personal relationships emerge in all their glory, anguish, and rage.

The book’s five sections, culled from previous editions of Vázquez’s work, are presented chronologically in order of publication. Many of these essentially surreal poems are written to a “you” who is neither introduced nor defined. This “you,” in various permutations, flits, stalks, or slithers through the poems’ textures like a procession of ghosts or archetypal figures whose emotional ambience ranges from seductive to sinister.

In section two (Poemas, 1988) Vázquez writes: “I waited for you to pick up the phone to say we should love each other, desire each other furiously until we roar with happiness.” Later, in “An Old Son” (from Erotica del Bolsillo, 1997), the mood is darker: “You have become a simple exterminator of sensibilities. From now on I will carry you as a eunuch carries his amputated part.”

The author’s short stories, poetry, and essays have been published in anthologies and periodicals in Spain, the United States, and throughout Latin America. In 2002 she was a winner of the prestigious Juan Rulfo prize for short story. A careful comparison of her Spanish originals with Rosa Alcalá’s English translations reveals that the poet’s intention is largely devoted to theme, image, and shock value rather than to subtleties of language. This, of course, makes the job of translation somewhat easier.

As the book progresses, there is a sense of growing control. Whereas the early poems seem entirely surreal, as though they were stream-of-consciousness ramblings from a disorderly psyche, the entire collection gathered in the last section is much more controlled. This section alone contains twenty poems, with such engaging titles as “The Hot Prison,” “When There Is A Corpse,” “The Walled City,” and “The Eunuch.” It is largely the linguistic skill and the control of image, metaphor, and overall structure of each poem in this section that justifies the inclusion of those wildly raving early poems. The comparison makes a very interesting study in the development of a modern Latin woman’s poetic voice.

Vázquez, who lives in New York and refers to herself as a “Caribbean in exile,” has left none of either her vocabulary or her temperament behind in the move. Forewords by both author and translator serve to bring the reader closer to an understanding of both the poet and the poems.

Reviewed by

Sandy McKinney

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.