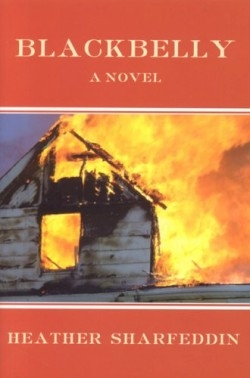

Blackbelly

Images of the Old West have become so ingrained in American culture that it’s difficult to imagine a Western-themed novel without a grizzled-but-kindly cowboy or a few six guns put to good use. The author, a rancher in Oregon, manages to rise above stereotypes with this first novel about the contemporary West, giving the familiar flavor of independence a new tang that’s both bittersweet and complex.

The story centers around Chas McPherson, who raises a breed of sheep known as Blackbellies, prized for their mild, tender meat. Although his ewes might ultimately melt in a diner’s mouth, McPherson is crafted of much tougher stuff, and has an angry, flinty edge honed from too many years alone. McPherson’s world begins to change when his father, suffering from Parkinson’s, begins to be cared for by Mattie Holden, a nurse with a barely concealed, complicated past.

Gradually unveiled is the father’s own dark past. Even though the former pastor can barely function in his later years, the townspeople still recall his fire-and-brimstone sermons, and his merciless strategy of finding out each individual’s sins and publicly revealing them. Although Chas is forty-one years old, he still retains the inward flinching of a child with an overbearing father, and his habit of wincing when confronted is less a sign of weakness than it is an acknowledgement of growing up under a storm cloud.

When the home of the town’s only Muslim family is burned down, the residents of the somewhat ironically named Sweetwater point their fingers at Chas, in a gesture of still-embedded fury over his father’s “work.” As the sheriff investigates the arson, Chas and Mattie begin to confront their own demons, and to find some solace in each other, like shipwreck survivors clinging to the same island.

Sharfeddin draws her characters carefully, but with spare detail. Although she provides readers with the characters’ ages and quick descriptions of their appearances, they’re still given a great deal of room to fill out. In some ways, they’re like postcards at the beginning of the novel, with only a sensation of place and time and a sense of vague familiarity at the outset. But as Mattie settles in, and the subsequent arson brings up issues of bigotry and intolerance, the characters become more tangible and complex, with memories that are surprising and multi-layered.

In many ways, the characters are like the landscape that Sharfeddin describes so well, victim to nature’s whims and yet with a sense of vast possibility that keeps their roots growing. This is a new kind of Western, and one that deserves to flourish—a glimpse of family dynamics and contemporary issues, set in a world where the Blackbellies roam.

Reviewed by

Elizabeth Millard

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.