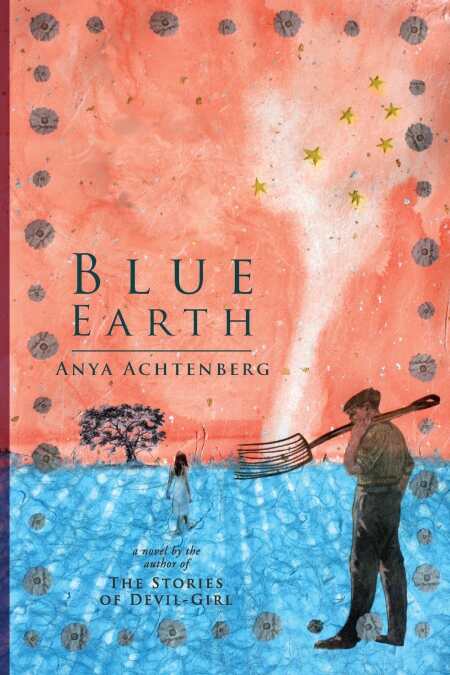

Blue Earth

Dreamlike retrospection begins a slow motion version of the tornado with which this novel opens, spiraling down through seemingly bottomless layers of memory to alter psychological terrain as relentlessly as wind and rain reshape the landscape. The novel’s precipitating event—the 1862 hanging of thirty-eight Dakota men—occurs long before the story begins, but it lingers like a poisonous aura through which its characters struggle to breathe.

Carver Heinz loses his farm and moves to the Twin Cities to work as a gas station attendant. His only lasting legacy from his family’s seven generations of backbreaking farm labor on formerly Dakota land is a narrative about his “right” to both the land and “his” women. Drifting in and out of recurring memories, Carver attempts to find affirmation in a life dominated by brutality and rage and only dimly penetrated by his imagined relationship with Angie, the “angelic” daughter of his friend, Mopstick.

Mopstick and his wife, Barb, seem like a caricature of love to Carver; Mopstick is inexplicably devoted to his “ugly” wife, a large woman whose face is scarred from multiple bouts of skin cancer. During the long years of her dying, Barb attributes her illness to the pesticides that warred against nature on her family’s farm and the brief role she unwittingly played in America’s weapons industry. Whereas Carver sees only imperfect surfaces, Barb understands that even inadvertent complicity functions like the metastasized cancer cells attacking her lymphatic system, exacting retribution from within.

This novel’s meandering path through the storm of memory seems repetitive and baffling at first and certainly does not constitute a light read. However, contemplative rereading yields an accretion of meaning and connectedness that is ample reward for the effort. When Angie falls in love with a Dakota schoolmate, Carver’s barely suppressed racism lurches violently awake, ready to protect Angie’s pure white skin from defilement. Although this event seems climactic at first, it is merely the beginning of a long journey to the novel’s true heart. Carver’s misanthropy casts a long shadow, but his halting quest for a genuine relationship governs the narrative’s contemplative pace, which occasionally flashes back to suggest new stories about old events. Timed to coincide with the sesquicentennial of the Dakota uprising, this novel’s wonder lies more in what we learn than one might expect from its bewildering forays into moments carved into the past.

Reviewed by

Elizabeth Breau

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.