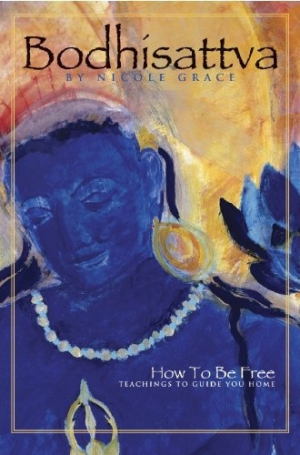

Bodhisattva

How To Be Free, Teachings to Guide You Home

Good poetry comes from a poet’s soul and touches readers’ hearts, thus sparking a natural affinity between poetry and spirit. The expression of specific religious ideas in verse sometimes fails to achieve that end, resulting in trite or dogmatic poetics. Those who write from deep spiritual feelings, such as Gerard Manley Hopkins or Thomas Merton, have given us writing mystical poetry of more widespread and timeless appeal.

Nicole Grace bases many of the poems in Bodhisattva on everyday observations of nature near her home in New Mexico. She differentiates between religious and spiritual thought, and the intent of this volume is to bring readers closer to understanding their spiritual nature. These narrative poems demonstrate how the personal ego and desire for physical pleasures obscure the simple joys in one’s life as it evolves. The author writes about common missteps along the way, but also reminds readers of the benefits and rewards awaiting those who choose to follow a spiritual path. Rich in analogy, the poems vary in length from two words up to a few pages.

Grace has gained the requisite experience to write spiritual poetry. An ordained Buddhist monk, she teaches Tantric Buddhist mysticism and meditation and conducts seminars internationally, guiding participants in personal and professional development. She has published numerous articles on these subjects and a previous book, Mastery at Work.

In “Begging Bowl,” the author compares her search for pine nuts in the cold autumn air to that of an old monk begging for food. She describes the laborious task of prying the nuts from their pine cone hideouts with fingers covered in sticky residue.

Carrying a beggar-like bowl, she looks:

“For a few pine nuts

Tucked like babies in a crib

Into the crooks of the cones.”

“The Best” concerns people who envy others and wish they could be like them, have what they have. The poem demonstrates the futility of this envious yearning and urges readers to cultivate their true selves. She writes,

“Then instead of

Becoming a

Shadow of someone else,

…You can be the

World’s only example

Of the best of

Yourself.”

The author witnesses three steaming meteor rocks falling to her driveway and contemplates time from both mortal and immortal perspectives in “Meteor Shower.” She considers the meteor’s origination and wonders that it traveled through inconceivable time and space to reach her.

“I stood there

Motionless

Gaping at these

Glowing gifts

Bits of stars

Millions of light years

Old and

Far away.”

The focus on spiritual awakening never falters in this book. Many poems successfully transform personal reflection into moving message. Grace’s tendency to write in the passive voice results in statements of certainty that sound less poetic. Pages ninety-three to ninety-seven were repeated during the printing process.

Those who look to poetry for spiritual understanding will value this book. The last poem, “Language of Eternity,” takes the reader beyond words to reach that goal.

“Silence is the

Language of Eternity—

Be Fluent.”

Reviewed by

Margaret Cullison

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.