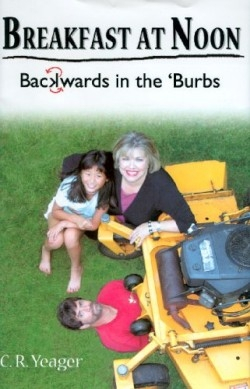

Breakfast at Noon

Backwards in the 'Burbs

The dubious pleasures of living in the suburbs, where raccoons use window boxes at will as latrines and cars are apparently smarter than their drivers, are the focus of these essays by Yeager, diagnosed as dyslexic and a stay-at-home dad who has a decidedly different take on the way the world works.

Yeager’s “backwards” look at his life in suburbia with wife Marsha and adopted daughter Anna spans everything from living with wildlife (“Personally, I have no illusions about nature: if it’s moving toward me I’m in reverse”) to living with neighbors (“Working from home, I know where all the Mad Moms are”), and has a decidedly sardonic tone. He raps nature, marriage, parenthood, and childhood with equal derision, and while his essays are definitely witty, they are a bit much to take all at one time.

The book is divided into six sections. It opens with “Castle Besieged,” in which he recounts tales of his family’s life in suburbia, including encounters not only with the aforementioned wildlife but also run-ins with the wild electricity of lightning, the hazards of severe weather, and the suburban phenomenon of garage sales. Next, in “Faith in Gravity: Parents,” he regales the reader with glimpses of life with his parents and in-laws; one sees the isolationist tendencies he learned from his own parents come under siege from his wife’s. In “The Pounding on the Stair: Parenting,” he takes on his own and his wife’s roles as parents, again with a decidedly offbeat approach.

Yeager’s unusual viewpoint continues in “Not a Transvestite: Espousal Issues,” in which he rambles from the subjects of health, sleep, and marriage to that of sartorial wisdom. He deconstructs women’s handbags and the torture value of their shoes, and moves on to the poignancy (or not) of the rediscovery of lost loves. Next are “Automobiles and Other Beta Blockers,” offering a glimpse of how he envisions corporate-run medical care — a do-it-yourself kit and instructions.

Finally, in “The Fresh Prince of Back Hair: Intimations of Mortality,” he offers an essay on the subject of handwriting — “Postscript,” the most moving in the whole book — in which he first recounts the emotional impact of a glimpse of his father’s handwriting, and its ability to conjure up the ghost of the man himself. He then laments the gradual disappearance of handwritten letters and the resulting loss of that emotional impact on future generations.

Laced with Briticisms (Yeager’s mother is British, although he grew up in Ohio) and sharpened barbs, the author’s very literate take on the world is definitely deflating. Witty he may be, but his forte shines forth when he veers a bit more toward the emotional. Yeager is definitely at his best when he allows his more serious side to come forth, as it does in the aforementioned “Postscript.” While they are best taken in small doses, there are resonances here, particularly for suburban dwellers and parents alike.

Reviewed by

Marlene Satter

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.